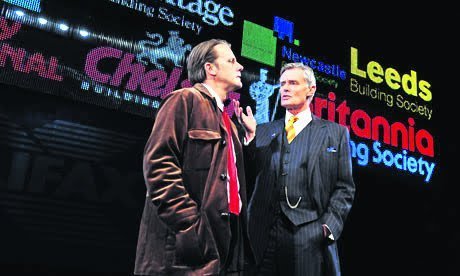

London’s West End recently staged a new play by David Hare about the recent crisis. Serious plays are thin on the ground nowadays so Mick Brooks went along to find out what this one had to say.

The play opens by asking the audience if we remember the day

in 2007, “when capitalism came to a grinding halt.” The speaker assumes that,

“greed and fear drive capitalism” but the financial crisis hit, “because there

was too much greed and not enough fear.”

An actor playing David Hare (the playwright and main link

character) then sets out to interview members of the financial ‘community’

(really a nest of vipers) to find out what the present crisis is all about.

The dialogue is based on what leading participants actually

The dialogue is based on what leading participants actually

said, or on a close paraphrase, and the play sparkles with one-liners. For

instance we find out that billionaire George Soros likes Britain because, “an imperial power

in its last throes is always the pleasantest place to live.”

David Hare introduces us to Myron Scholes, a mathematical

‘genius’ who won the Nobel Prize for economics. He demonstrates on a blackboard

with incomprehensible equations how it is possible to make money risk free!

Scholes helped found Long Term Capital Management to make money for himself out

of his theory. LTCM went bankrupt a decade ago and is still being pursued by

the US

government for tax evasion. We are reminded that Merton-Scholes theory is still

taught as standard in business schools, despite its literal bankruptcy as a

theory.

We are introduced into the fevered atmosphere of the past

boom – the fairyland of finance and the suspension of disbelief over the past

few years as fabulous sums changed hands. The Financial Services Authority (the

body set up by Gordon Brown to regulate the industry) practiced ‘light touch

regulation,’ which, it is explained, really meant no regulation. The result is

“the biggest boom – and the biggest bust” ever.

Hare takes us to the housing bubble in the USA where, at its

peak, there were one million mortgage brokers selling sub-prime mortgages to

people who could not possibly keep up the payments. Rating agencies accredited only AAA security,

because that is what they were paid to do. How was the prosperity of a few

years back possible? Beyond the bubble in house prices and mad lending of the

banks was the reality of hundreds of millions of Chinese working for 36 cents

an hour to produce the goods many in the West bought with the Mickey Mouse

money.

Hare brilliantly displays the absurdities of the system; the

way that sub-prime mortgages were bundled up and sold all round the world. This

bogus accountancy even fooled those who had invented it. Barclays’ balance

sheet was garlanded with “non observable inputs” (the banking equivalent of the

emperor’s new clothes). It came to a point where bankers said to themselves,

“If you can’t believe our own balance sheet, how can you believe other

people’s?” Inter-bank lending froze as a result in 2007. The credit crunch had

begun.

Treasury officials were actually attending a seminar on the

current economic prospect called ‘The Great Stability’ when they were invited

to turn on their TVs and watch people queuing up outside branches of Northern

Rock, desperate to get their money out before the shipwreck.

Things went from bad to worse in 2008 when Lehman Brothers

was allowed to go to the wall. Why? Hare suggests it was because Bush’s

Treasury Secretary Paulson was a Goldman Sachs man and the US Treasury itself

was stuffed with people from arch-rival Goldman Sachs. It’s an intriguing

thought.

Faced with financial meltdown, “the commitment to the free

Faced with financial meltdown, “the commitment to the free

market lasted just one day.” Taxpayers’ money was poured in to bail out the

banks. David Hare is writing a play, not a political pamphlet. Like dramatists

going back to the Greeks, he is anxious to examine human motivations. And what

a weird and dysfunctional bunch he uncovers! But he makes it clear that the

people he portrays are part of a system at work – or rather breaking down.

One of the most hilarious scenes is when the actor playing

David Hare interviews an astute Financial Times reporter (probably Gillian

Tett). CEO Fred Goodwin had just ploughed the venerable Royal Bank of Scotland into

the ground, thus threatening the livelihoods of millions of people directly and

indirectly. ‘Fred the shred’ was coached into showing contrition when he

appeared before the House of Commons Select Committee, contrition that he

certainly didn’t feel. He felt he deserved his £1m a year pension as a reward

for his abject failure. He was certain he hadn’t done anything wrong. He was

angry with ‘the markets’!

And how about those bonuses? Well, as one character

explains, workers in ice cream factories get in the habit of helping themselves

to ice cream whenever they feel like it. And the bankers work in money

factories.

David Hare cleverly intersperses insights into the paranoid

fantasies of the bankers with down to earth advice from a man from the

Citizens’ Advice Bureau on how to deal with the bailiffs, if you’re on your

down on your luck on account of what people like Fred Goodwin have done.

Sometimes the bailiffs are not as threatening as you think, since your debt has

been bundled up and sold, just like a sub-prime mortgage! Then on comes a bond

trader who feels betrayed (by us!) because he won’t be able to exercise his

god-given right to trouser squillions of pounds of money in the near future.

The title of the final scene is ‘The death of an idea – that

markets work.’ Public sector workers step forward and explain that managing a

hospital is harder than running a bank. For most of us it’s also more

important.

Are the politicians going to discipline the bankers?

Politicians are not in office for ever, one actor explains. And when they

retire, what more pleasant way to supplement their pension than to end up on

the board of a bank?

Were the ‘masters of the universe’ clever or lucky for so

long? David Hare lets us draw our own conclusions. He concentrates on the

activities in the financial system because a play has to be a human story. But

he makes it clear that the human failures are really failures of a system that

raises people like Fred Goodwin to the top. We can draw the conclusion that the

financial crisis was a trigger for a wider economic crisis – a crisis of

capitalism.

This play is by turns entertaining and thought provoking. It

makes you angry. It makes you think. You can’t say fairer than that.

The Power Of Yes continues at the National Theatre thru Jan to April. Contact the ticket office at 0207 452 3000 or go to their website at www.nationaltheatre.org.uk to book online