On 18 January 1981, a fatal fire tore through 439 New Cross Road in South East London. Inside, Yvonne Ruddock and around sixty teenage guests were celebrating her sixteenth birthday.

Thirteen young black people were killed that night. Fifty more were physically and mentally maimed. One guest, Anthony Berbeck, committed suicide two years later – most likely as consequence of the trauma from that night.

Never fails to shock us till this day the New Cross fire. May they continue to rest in peace??#SmallAxe pic.twitter.com/xoWHl6M0K1

— ??Uzoamaka?? (@TashAmaka) December 6, 2020

Nothing said

Despite the terrible fatalities, injuries, and harrowing after-effects, there was a marked lack of official response to the incident.

Margaret Thatcher, the prime minister at the time, felt it appropriate to wait five weeks to respond to a letter written on behalf of the families affected. Even more callously, Thatcher neglected to contact the families directly, instead requesting that her sympathies just be passed on.

This stands in stark contrast to the immediate condolences offered by both Thatcher and the Queen, just a month later, when forty-eight white victims were killed in the ‘Stardust Fire’ in Dublin.

Margaret Thatcher and the Queen refused requests to send a letter of condolence to the families in mourning. Shortly after New Cross, they sent condolences to a white family in Ireland who’d lost loved ones in a disco fire.

— Hol (@holly_rodman) June 3, 2020

Likewise, the families of the New Cross teenagers who died were offered minimal compensation; barely enough to cover even half the cost of burial. Meanwhile, those who survived, including the injured, were denied compensation for the mental and physical trauma they suffered.

Wayne Hayes – who shattered 163 bones that night and would undergo 140 skin grafts – has received no compensation to this day. Instead, he has struggled to maintain his disability status despite his injuries, having to fight to re-acquire his confiscated disability ID card.

Case unsolved

This grave mistreatment was accompanied by the ‘argument’ that the teenage partygoers were somehow responsible for starting the fire.

Police questioned survivors and pressured them to sign false statements. Denise Gooding, who was just eleven years old, was subjected to hours of questioning into the early morning.

Eventually, twenty-three years later, a second inquest ruled that the fire was indeed started deliberately. And yet, the police and judiciary system refuse to categorise the attack as racially motivated. Consequently, no one has ever been charged and the case remains unsolved.

Far-right extremism

This is in spite of the fact that there was every indication that the fire was a product of far-right extremism.

For instance, the New Cross massacre was not the first time a devastating fire had torn through a black Caribbean gathering in South London.

In 1971, a Caribbean house party in Forest Hill was attacked by a firebomb and twenty-two guests were injured. Furthermore, in 1978, the Albany Empire Community Theatre in Deptford – a spot frequented by black people in the local area – was burned down by members of the National Front, a far-right organisation.

3 years prior your own organisation admitted it burned down Deptford’s Albany Empire community theatre. So your racist outfit boasted about arson then you insist you’re not aware of any racism. Are you a rubbish boss or a liar?

— Cannonball Adderley. (@Steve16711988) January 18, 2021

The New Cross fire at the hands of the far right – along with the tepid police and judiciary response – are expressions of the racism that black people have long suffered in Britain.

Racially motivated violence has in many cases been accompanied by police abuse, as well as neglect by the state.

It is clear that this had not withered away by 1993, when the racially motivated murder of Stephen Lawrencewas similarly mishandled and neglected by the Metropolitan Police. It was only in 2012 that two of Stephen Lawrence’s five killers were finally convicted, against a background of police corruption and cover-up.

Mass response

Importantly, the events of 18 January 1981 led to a renewed mood of militancy and organisation within the black communities in London and other cities. This demonstrated a radical shift in the consciousness of black people in Britain.

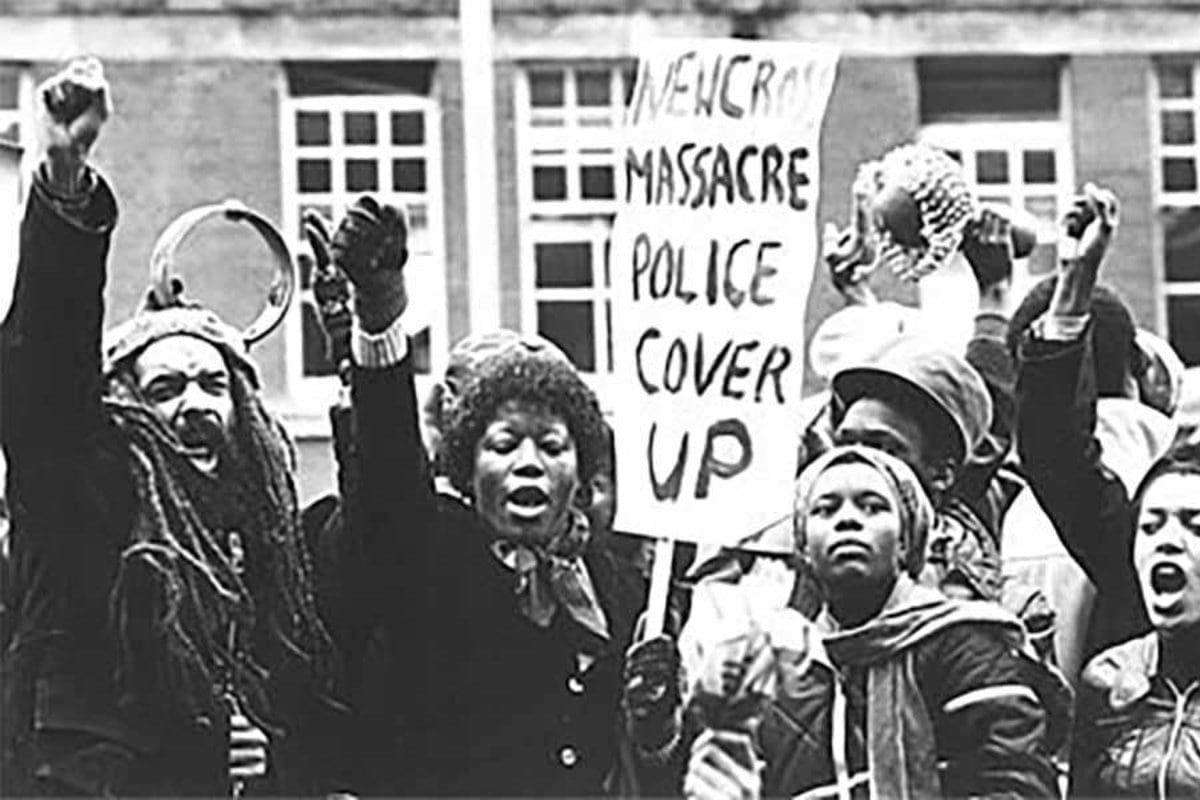

Shortly after the fire, over 300 people attended a community meeting where the New Cross Massacre Action Campaign (NCMAC) was established. This would prove vital for building momentum for the National Black People’s Day of Action on 2 March 1981.

On that day, more than 20,000 protesters marched across London alone, bringing the city to a stand still. This sparked a series of nationwide uprisings, including the Brixton Riot of 1981.

The organised movement focused on tackling systemic issues through community self-help; an attempt to make up for the poor treatment, care, and education offered to black people by the state.

These grassroots efforts no doubt had a positive impact. For example, the much-despised ‘sus law’ – which gave the police powers to undertake racist stop-and-search practices – was repealed in August 1981, off the back of mass protests and community activism.

But such initiatives alone could not and cannot solve the issue of racism in Britain. Indeed, racist profiling and the excessive policing of black communities are as rife as ever. This explains why movements such as Black Lives Matter have exploded onto the streets, finding an echo across the UK.

A systemic problem

Racism is used as a tool by the ruling class to divide the working class, so as to undermine class solidarity. So long as capitalism exists, therefore, divisions that perpetuate racial discrimination will continue.

Racism is used as a tool by the ruling class to divide the working class, so as to undermine class solidarity. So long as capitalism exists, therefore, divisions that perpetuate racial discrimination will continue.

The response of the police, the politicians, and the whole establishment to the New Cross fire illustrates the fact that racism is a systemic issue, and not just an individual problem.

Ultimately, therefore, reforms and community initiatives cannot confront the root cause of racism, because they leave this oppressive system – capitalism – fundamentally untouched.

We need a united movement of workers and youth around class-based demands – for decent jobs, housing, and services for all – to abolish this racist and exploitative system of the bosses, and bring about a socialist society, where the working class and their communities are in control.

Only then can racism be overturned once and for all, bringing about a permanent end to racial prejudice and violence.