We are frequently told that the working class is no more and that class in 21st century Britain is simply a matter of social tastes. We are supposedly “all middle class now”. Martin Hall of the Bristol Marxists examines the real nature of class in British society today.

We are frequently told that the working class is no more and that class in 21st century Britain is simply a matter of social tastes. We are supposedly “all middle class now”; placing society into two hostile camps – bourgeoisie and proletarian – is apparently a thing of the past.

A recent BBC article attempts to deal with the evolution of the middle class, but cannot reconcile the contradictory data it has gathered from its ‘class calculator’. Indeed, according to the survey, most people define themselves as working class. Scratch beneath the surface and you’ll find that society is more polarised than ever and that the bourgeois concept of the middle class is a myth.

What is class?

Marxists see class as a social relation; something material and real as opposed to an individual’s state of mind or cultural preference. Throughout history, we see society organised around a mode of production. We can broadly break these down into slavery, feudalism and capitalism. Within each system, there have been different classes with a specific role in production. As Marx explained in the Communist Manifesto (1848):

“In the earlier epochs of history, we find almost everywhere a complicated arrangement of society into various orders, a manifold gradation of social rank. In ancient Rome we have patricians, knights, plebeians slaves; in the Middle Ages, feudal lords, vassals, guild-masters, journeymen, apprentices, serfs; in almost all of these classes, again, subordinate gradations.”

To put it simply, there are those in society that own the means of production and those that don’t; those that own wealth and those that produce it. In previous forms of society, this economic exploitation was more obvious. In ancient times, that which was produced was appropriated by the slave owner, while the slave was simply the property of the slave owner – a tool with a voice.

In capitalist society, exploitation takes a different form. The capitalist owns the factory or call centre, and sets wage earners to work. The key difference between these two forms of society are that under capitalism, the boss does not maintain his employee in the same way a master keeps his slave. The worker has no guarantee of accommodation or food and instead has to buy the necessary things with the wage he earns from the capitalist. The vast majority of society fit into this category of “wage slaves” – of people who have no choice but to sell their ability to work to the owners of capital; in other words, no choice but to earn a wage in order to live. In fact, the proportion of wage-workers worldwide is higher than it has ever been.

Class society today

Of course, many will argue that class is more nuanced than this. Indeed, the BBC class calculator puts people into one of seven classes: the elite; established middle class; technical middle class; new affluent workers; emergent service workers; traditional working class; and the “precariat”. It concludes that the traditional working class is “smaller than it was in the past” and that it is largely being replaced with affluent workers and emergent service workers.

The survey further complicates the nature of class by claiming to measure social and cultural capital. It askes questions such as what sort of friends people have, e.g. postal workers or chief executives, in order to garner how much social capital they have. In terms of cultural capital, they pose such questions as, “what kind of music do you like listening to?”

A breakdown of the results gathered reveals that the working class account for the majority of those interviewed. The precariat, emergent services workers, traditional working class and new affluent workers, when combined, account for nearly 65%. These people are all wage-workers and can therefore be defined as working class.

The BBC also interviewed a newly qualified solicitor who is within the new ‘Emergent Workers’ section. They characterise this “new class” as having low income, yet at the same time high cultural capital. The person in question occupies a role that was once seen as middle class. Roles like solicitors, teachers and lecturers – all requiring university education – are all now working class. This is part of a trend that runs counter to the prevailing notion of a growing middle class. This trend was, in fact, predicted by Marx and Engels:

“The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage labourers…

“…all these [petty bourgeoisie roles] sink gradually into the proletariat, partly because their diminutive capital does not suffice for the scale on which modern industry is carried on, and is swamped in the competition with the large capitalists, partly because their specialised skill is rendered worthless by new methods of production.”

Roles that would have been traditionally seen as petty bourgeois – i.e. middle class – have been subsumed into the growing working class. The World Bank charts this development, and counts waged and salaried workers as being close to 85% of the UK population.

Moreover, if we look at statistics on wealth, the image is even more striking. According to an ICM poll, the richest 20% own 60% of the wealth. The richest 1% have as much wealth as 60% of the population! Taken together, that doesn’t allow for a particularly large “middle class”.

The middle class

So what of the new class calculator? What is most relevant from this new survey is that the majority of people don’t like to be placed within a class, with only half of the population spontaneously placing themselves as belonging to either class, and with others only doing so when prompted to put themselves into one camp or the other. This reveals the illusions many people have within capitalist society. Many people don’t want to define themselves as working class because they are trying to emancipate themselves from it!

Capitalism differs to previous forms of society in that rising from one class to another is a possibility – albeit a very abstract and utopian one for most people. In fact, social mobility is key to capitalism’s survival. How else do you perpetuate the miserable character of working life if there isn’t the prospect of social development? Capitalism called into existence such a large class of workers that it is impossible to suppress this class (though the state has the police and the army at hand if things get revolutionary!); so a war is waged to convince people that they can better themselves by rising out of the working class and joining the ranks of the middle class.

This illusory idea of social mobility is seen in its most developed form in the “American Dream” – of home ownership, a car in the garage, a swimming pool in the yard and a university education for your children. In the UK, this dream was lampooned in such sitcoms as ‘The Good Life’ and ‘Keeping up Appearances’, the latter of which featured the repellent and laughable Hyacinth Bucket (pronounced “bouquet”).

Key to the middle class myth is that if you work hard enough and make the right connections, you too can become a member of the capitalist class. For some, this happens and there are a number of rags-to-riches stories out there. A vast amount of modern cinema and literature is based on that very fantasy! However, the very idea that you can become a capitalist (see programmes like “Dragons’ Den” or “The Apprentice”) presupposes the existence of class society! Not everyone can be a capitalist. The wealth in society must come from somewhere. As the saying goes, “Not a light bulb shines, not a wheel turns, not a telephone rings, without the kind permission of the working class”.

The evolution of the middle class dream

The post-war economic boom – the “Golden Age” of capitalism, laid the material basis for the idea that “we’re all middle class”. The economic boom, which preceded the global slump in the 1970s, saw a huge increase in the living standards of the working class. With this came full employment, free healthcare (at least for Western Europe), and a strong trade union movement.

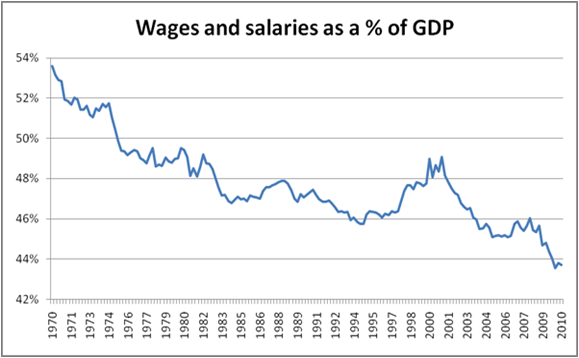

In the 1980s, the traditional organisations of the working class came under ferocious attack from the Thatcher and Reagan governments. Following the crisis of the 1970s, Western leaders tried to break up the trade union movement in an attempt to claw back the share of wealth that went to worker’s wages. The whole period following the global crisis in the early 1970s, of roughly 30-35 years, saw a huge fall in labour’s share of GDP.

In the 1980s, the traditional organisations of the working class came under ferocious attack from the Thatcher and Reagan governments. Following the crisis of the 1970s, Western leaders tried to break up the trade union movement in an attempt to claw back the share of wealth that went to worker’s wages. The whole period following the global crisis in the early 1970s, of roughly 30-35 years, saw a huge fall in labour’s share of GDP.

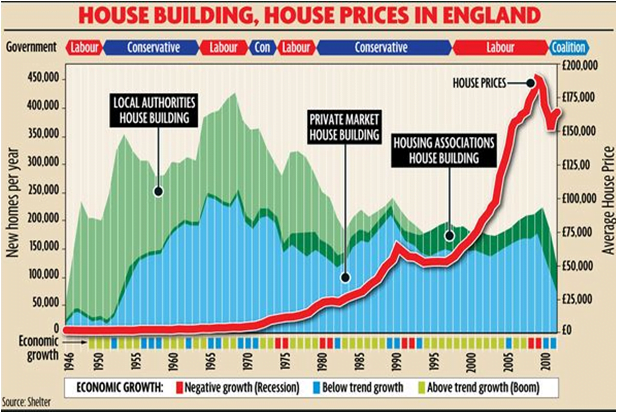

As part of their attempt to curb the power of the labour class movement and restore profits, the ruling class attempted to buy off workers with home ownership and share options. In the UK, this was seen with the ‘right to buy’ scheme, whereby the Tory government under Thatcher orchestrated a huge sell-off of council housing. This led to many working class families buying their council homes at a fairly cheap price and then seeing the value of their house rise over the course of the 1980s and 90s. Indeed, in the early 80s the average cost of a home was close to £50,000. Before the 2008 crash, it had risen to almost £200,000.

The selling off of council homes and a myriad of other pro-market policies resulted in a huge expansion of credit. Alongside this, the destruction of industry and manufacturing in Britain – through globalisation, de-industrialisation and offshoring – and the growing importance of financial services in the UK economy led to the abolition of many traditional “blue-collar” working class jobs. The UK economy was re-orientated towards “services” and “white-collar” jobs.

The selling off of council homes and a myriad of other pro-market policies resulted in a huge expansion of credit. Alongside this, the destruction of industry and manufacturing in Britain – through globalisation, de-industrialisation and offshoring – and the growing importance of financial services in the UK economy led to the abolition of many traditional “blue-collar” working class jobs. The UK economy was re-orientated towards “services” and “white-collar” jobs.

This process, however, did not create a new class or reverse the trend of “proletarianisation”. In order to restore the profitability of capitalism, pay and conditions also came under attack. Wages remained practically frozen throughout this period and continue to be painfully low to this day. In order to compensate, many people bought goods on credit. This was far from the reckless spending frenzy that the media often portrays. It did however foster an illusion of growing prosperity, and the growing consumerism that resulted also allowed many to believe that they were part of a new aspiring middle class.

The 1980s was a period of intense class struggle, with the ruling class gaining a narrow victory, as evinced in this country most clearly with the victory over the National Union of Mineworkers in 1985. The defeat of the miners was a huge victory for the capitalists, and a devastating blow for the working class.

After a period of growing militancy and a sense of class consciousness, the working class became increasingly atomised in the years that followed. In 1979, there were roughly 13 million people in the organised trade union movement, As of 2012, this number was roughly 6.5 million. From an ideological war being fought by the capitalist class to convince workers of the supremacy of capitalism; through promoting the middle class myth by selling workers council homes and shares in utilities; and coupled with the defeat of the organised working class: it is easy to see why the myth that we are all middle class grew in the decades that followed.

Precariat!

The BBC class calculator may have complicated the picture when it comes to class, but there is one notable distinction it has made; it has given The Economist and author Guy Standing’s term “the Precariat” a more public airing. Formed from the words, precarious and proletariat, this term applies to those who have little to no job security. According to the analysis of the Great British Class survey, the Precariat have all sorts of potential activities they like to engage in, but cannot do any of them because they have no money, insecure lives, and are usually trapped in old industrial parts of the country.

Standing defines the Precariat as an agglomerate of different social groups, comprising: immigrants; young educated people; and the industrial working class. Traditional working class occupations that guaranteed a secure income and decent pay and conditions have given way to part time work and zero hour contracts.

We are all working class now

Not many will doubt that class still exists, despite the attacks on the very idea. The capitalists still attempt to propagate the notion that the middle class is expanding, and that as part of an aspiring middle class, we might all share the same interests as the bourgeoisie. This explains the ridiculous statement by millionaire, Eton-educated, Prime Minister David Cameron, where he defined himself and his wife as part of the “sharp-elbowed middle class”. Similarly, Labour leader Ed Miliband and other reformists who have accepted the capitalist system in its entirety address the ‘squeezed middle’ when they make their appeal to the electorate.

The middle class myth grew out of the post-war boom period; and then more recently matured in an era of stagnant wages, where economic growth and household consumption was fuelled by credit. It was a period of relative class peace, with a weakened labour movement and the seeming infallibility of capitalism.

This has proven to be the calm before the storm. The class survey found that six out of ten people define themselves as working class. Many more who once considered themselves to be middle class are finding common class interests with fellow workers. The middle class myth may be strong in many minds, but the reality of the situation – of worsening living conditions and rising prices – is forcing many to realise that, in order to improve their position in society, they must fight not only for their own emancipation, but for the emancipation of their entire class – the working class.