On 24 May 1798, the Irish masses rose in revolt against British rule, under the banner of the United Irishmen.

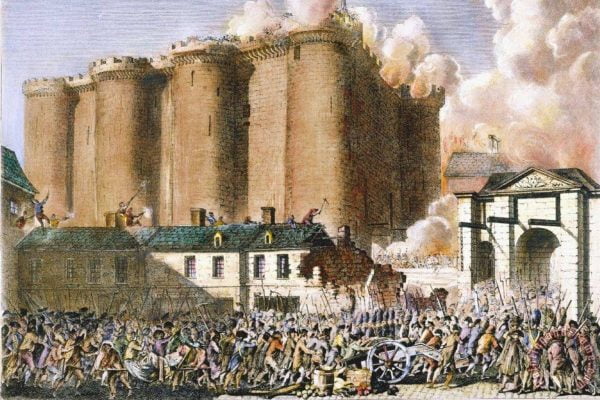

Inspired by the success of the American Revolution – the first crack in the ice of British colonialism – and the ideals of the great French Revolution, this radical movement struck fear into the hearts of the British ruling class.

Through appeals to the peasantry, the United Irishmen seriously undermined the rule of the landed aristocracy, who played second fiddle to the bankers and bosses in London.

The rebellion had a genuinely popular character, bridging the religious divide between Catholics and Protestants.

Today in Irish society, the rebellion is treated as a romantic tale of tragic heroes. But this historical episode is one from which republicans and revolutionaries must draw both inspiration and bitter lessons.

Beginnings

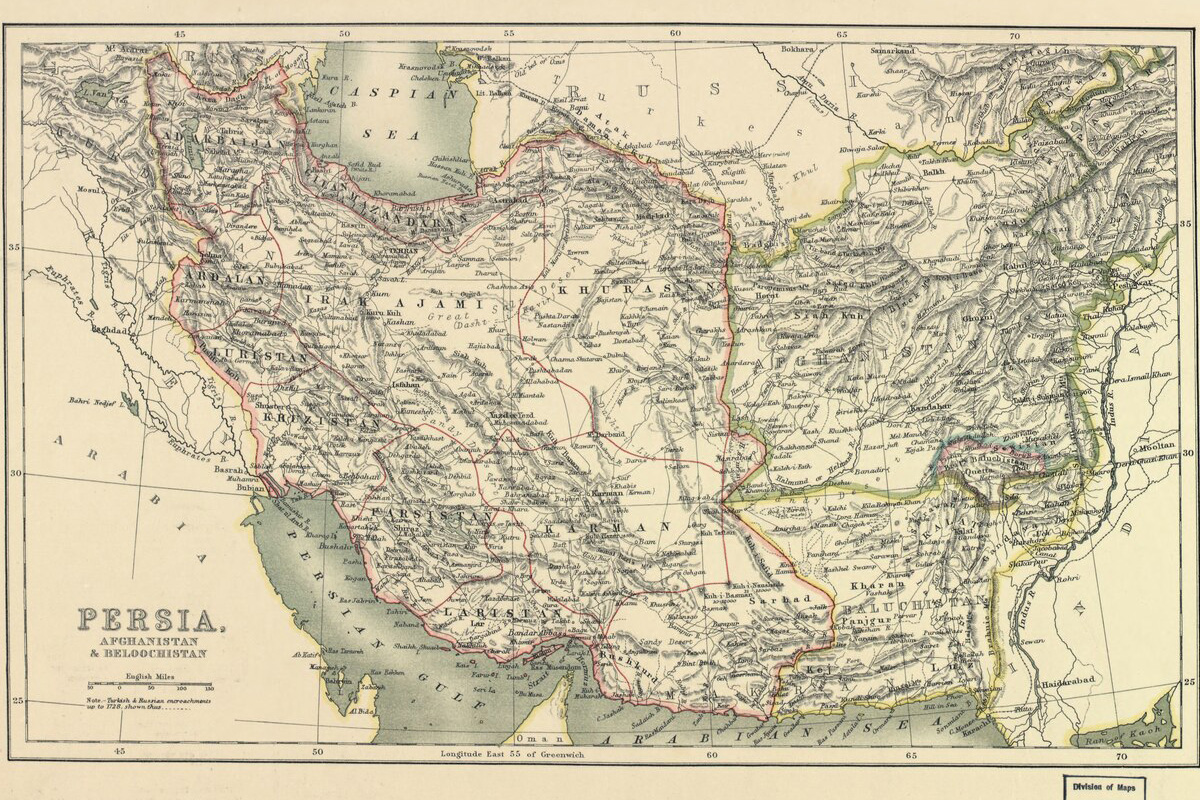

Ireland was England’s first colony, where the British ruling class perfected the dark arts of divide and rule. And at the end of the 18th century, Ireland was a hotbed of turmoil and discontent under the domination of the British elite.

The peasants were crushed by high tithes and rents. And Catholics more generally were unable to vote, or enter certain professions.

The merchants and artisans in the cities were wracked by high taxes and restrictions on trade. Poor harvests and declining wages all fed into the broader economic malaise.

The French Revolution – which struck blows against the landed aristocracy and the monarchy, leading to the fall of the ancien régime and the declaration of a bourgeois republic – resonated with the impoverished Irish masses.

It was against this backdrop that the Society of United Irishmen was founded in October 1791, swearing to reform the country on “principles of civil, political, and religious liberty”.

Its membership consisted of both Catholics (such as leaders like Wolfe Tone) and dissident Protestants.

One preeminent figure of the movement by the name of Henry Joy McCracken, a Presbyterian textile manufacturer, would later lead the insurgents at the Battle of Antrim.

McCracken was acutely aware of the limits of his fellow merchants, who were reliant on their English counterparts for profits. He commented that they would rather “see the whole island, and every vestige of [its] liberty, sunk into the sea”, than have their bottom line threatened.

‘Men of no property’

Most of the well-to-do members began to drift away once the British ratcheted up their repression, forcing the Society underground.

As McCracken predicted, with their power, prestige and property on the line, the wealthier elements gave up the struggle for national liberation before it had really begun.

The remaining United Irishmen drew important conclusions from this. In the immortal words of Wolfe Tone: “If the men of property will not support us, they must fall. Our strength shall come from that great respectable class, the men of no property.”

The Society turned to the peasants, artisans, and emerging working class. They understood that the national struggle was inseparable from the struggle of the oppressed classes in society – the struggle against landlordism, poverty, and exploitation.

This message struck a chord with the developing mood in society. In Dublin, for instance, combinations across various trades were garnering reputations for their radicalism.

Agrarian societies had long been established amongst the peasantry, to defend communities against high rents and tithes. The United Irishmen appealed to these societies, linking them up to the nationwide movement and its broader political programme, and preparing for an armed revolt.

Through these methods, huge swathes of the peasantry – both Catholic and Protestant – were won over and the stage was set for the rebellion.

Rebellion

When the signal for revolt went out from Dublin, the masses responded heroically. The people rose up across the entire country, and were able to win a number of impressive victories.

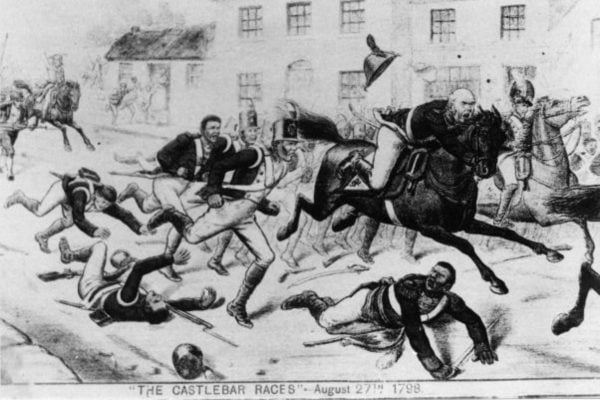

Rebels were able to occupy large parts of County Wexford at the height of the insurrection. Others, with the assistance of a small French contingent, humiliated the government at the ‘Castlebar Races’ in August.

Yet bravery and conviction alone were not enough. Most importantly, the leaders had not worked out a coherent programme of their own, and the masses were forced to look elsewhere for leadership in the white-heat of struggle.

With the arrest of most of the Society’s executive on the eve of revolt, the masses turned instead to any educated person they could find: disaffected clergymen, sympathetic landlords, and others swept up in the movement.

The urban workers in the cities, particularly the apprentices, were undoubtedly amongst the most radical layers. Yet they were restrained on the part of the ‘middling orders’, who were increasingly afraid of the social unrest which could be provoked.

One informer remarked that the merchant bourgeois were deeply disturbed by the idea of a rising in Dublin. Their appetite for revolt amongst the petit-bourgeois was dissipating the more the masses surged forward. Many vacillated, provoking confusion and disorder. In the end, there was no uprising in Ireland’s largest city.

Across Ireland, the hesitation of the leadership proved to be one of the greatest obstacles. As was written by McCracken, and proved a thousand times over in national liberation struggles to come: “The rich will always betray the poor.”

The Orange Order

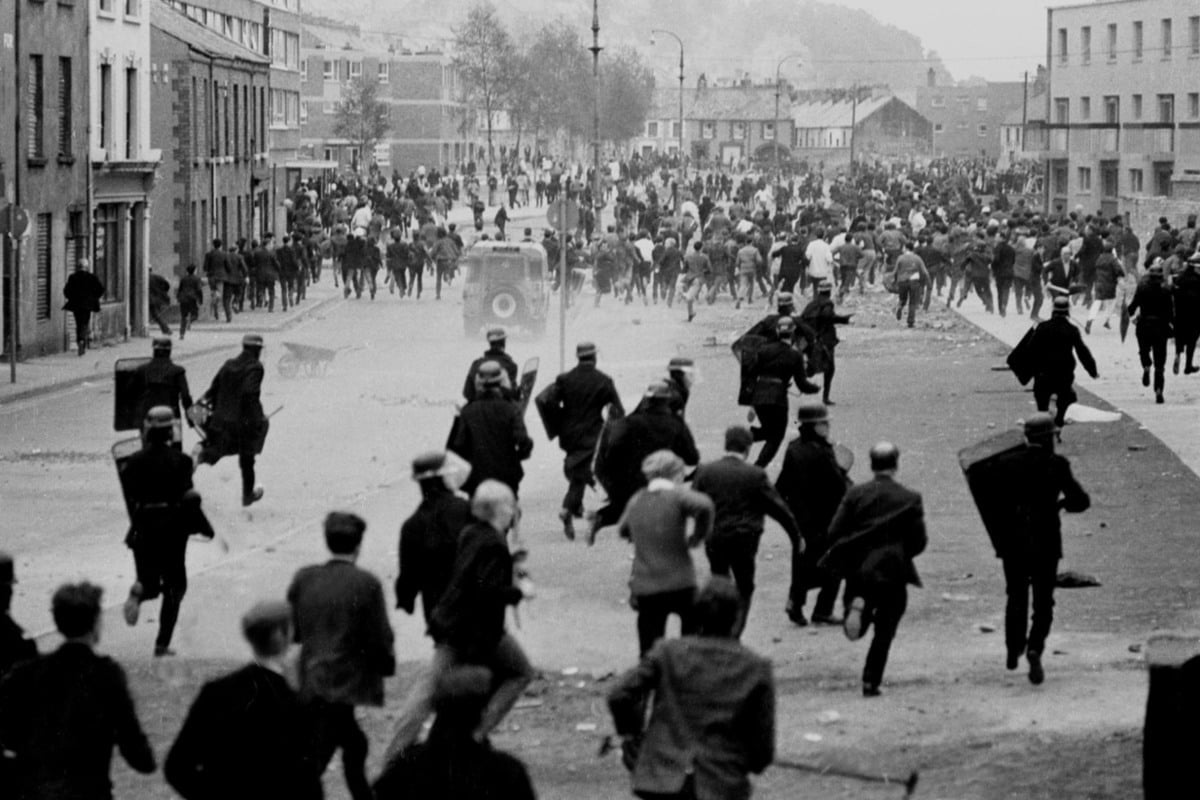

Though defeated, the revolutionary events of 1798 made the British ruling class aware of the mortal threat posed by a united movement of the Irish Protestants and Catholics.

All their efforts turned to destroying that unity. The main weapon that the ruling class relied upon was sectarianism: the fomenting of divisions between Catholics and Protestants.

In the run up to the rebellion, this included the arming and deliberate mobilisation of the Orange Order – infamous since its founding in 1795 for its brutal sectarian violence against Catholics and ‘disloyal’ Protestants.

Such ‘divide-and-conquer’ tactics were subsequently deployed by British imperialism – in Ireland and across the world – for centuries to come.

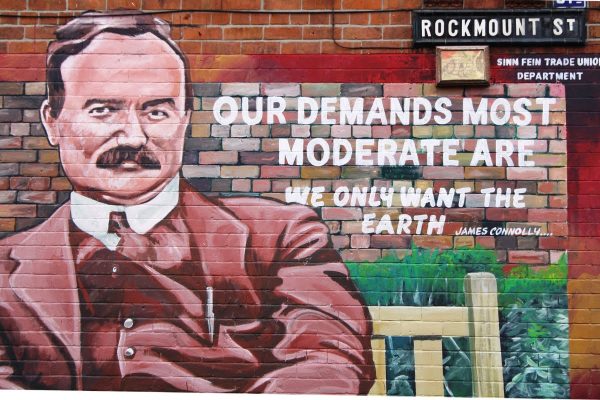

But as was understood by the best elements of the Irish Republican movement afterwards, most notably James Connolly, the only way to cut across this poison of sectarianism is by striving for the maximum unity of the working class – pointing out the common class interests between Catholic and Protestant workers, against the bosses and bankers.

Out of print since 2005, this book’s re-release with a new introduction couldn’t come at a more appropriate time as British imperialism lurches from crisis to crisis & the Union frays at the seams. A must-read for revolutionaries in Ireland, Britain and beyond. https://t.co/w8sT7FfOzW

— Ben Sea (@everythingcrash) September 23, 2022

Lessons

There are many bitter lessons to draw out from this tempestuous period of history. The vacillations of the middle-class leadership laid the basis for reaction. Martial law was declared; thousands were arrested; and the public flogging of suspected rebels became a common sight.

Contemporary evidence suggests a total of at least 30,000 dead. Rebel leaders like McCracken were hanged, and Tone only escaped execution by slitting his throat.

The weak and degenerate bourgeois in Ireland was – and remains – tied by a thousand threads not only to foreign capital, but to the class of landowners who the masses valiantly rose up against.

Learning the tough lessons of the Irish rebellion, James Connolly commented that the working class alone are the “incorruptible inheritors of the fight for freedom in Ireland”.

However deep the rebels of 1798 were buried, the struggle for Irish national liberation has not gone away. Indeed, rebellion runs like a red thread throughout Irish history.

The experiences of the uprising prove that overcoming the monster of sectarianism, fed by the ruling class, is not only possible but necessary in the struggle for a united, socialist Ireland.