The spread of the coronavirus across China is starting to have serious political repercussions for the regime. Social tensions are heightening, the economy is stalling, and the stability of the system is under threat.

Weeks after the outbreak of the new coronavirus, the officially reported cases of infection throughout China have reached well over 40,000. The cities under the “lockdown” orders from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) extend from Hubei Province, the center of the outbreak, to Zhejiang, Henan, Shandong, Heilongjiang, Fujian, and Jiangsu Provinces, covering a total of 27 cities and over 50 million people. The scale of this containment is historically unprecedented. Beijing and Shanghai have also been declared to be under “half-lockdown” state.

The spread of the virus to other countries has also led the World Health Organisation to declare the coronavirus outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern.” This viral outbreak, which has spread further than the SARS epidemic in the early 2000s, may also turn out to be the biggest political challenge to the CCP regime since Xi Jinping took the helm.

Economic shock

The daily lives of millions of Chinese people have been severely disrupted by the virus and the CCP’s countermeasures. Many cities in Wuhan are enforcing strict control over residents’ movements, while traffic controls of varying degrees have been stepped up across the country. The world’s second-largest economy is gripped by a mood of fear, which in turn adds to the already decelerating economic growth rate.

The daily lives of millions of Chinese people have been severely disrupted by the virus and the CCP’s countermeasures. Many cities in Wuhan are enforcing strict control over residents’ movements, while traffic controls of varying degrees have been stepped up across the country. The world’s second-largest economy is gripped by a mood of fear, which in turn adds to the already decelerating economic growth rate.

It is generally understood that the tourist, food, hospitality, and the air travel industries inside China will suffer the first impact from the slowdown of circulation of goods and services and the decline of consumption caused by the epidemic, while consumer services such as internet shopping will also be affected. In this situation, the small-and-medium enterprises that cannot withstand this economic shock may go under.

According to an estimate by the team around China’s Evergrande Group’s chief economist Ren Zeping, compared to the lunar new year period of 2019, China’s cinema industry has lost 7 billion RMB in revenue (around USD $1 billion), the retail restaurant industry has lost 500 billion RMB (around USD $71 billion), and the tourist industry has lost another 500 billion RMB. The losses from these three industries alone amount to the equivalent of 4.6 percent of China’s GDP in the first quarter of 2019. Wang Chenwei, deputy researcher at the government’s China Society of Macroeconomics has also predicted that the epidemic may put more pressure on China’s foreign trade, while investment activities may also decline.

More importantly, the economic shock that the epidemic has levied on China is taking place in the context of a world economy in crisis. Ren Zeping’s reporting points out:

“Some believe that the economic impact of the novel coronavirus will be no more (severe) than that of SARS. We believe this is overly optimistic. In 2003, China’s economic growth rate was as high as 10 percent. Now it is under pressure to stay at 6 percent. In 2003, China had just joined the WTO, the population dividend was paying off, and the increase in exports had reached 30 per cent. Today, with the frictions from the Sino-US trade war, the aging population and the general increase in costs, the growth rate of exports in 2019 was only 0.5 percent, nearing zero. In 2003, China was in the early phase of economic revival, now the Chinese economy has been slowing for over ten years, in addition to the effect of financial deleveraging and Sino-US trade war, the epidemic will inevitably exacerbate the situation for businesses. Furthermore, in the early phase of the 2003 SARS outbreak, production was not impacted due to suppression of information, whereas today the measures (of the government) have been more immediate and decisive, which will also clearly impact on the economy and all industries.”

Ren Zeping and other Chinese economists, both official and private, all tend to present an ultimately optimistic outlook for China’s eventual economic recovery. But Marxists understand that, whether in China or elsewhere around the world, the capitalist system is in a state of senile decay, which paves the way for economic crisis globally. Even before the outbreak, the Chinese economy’s slowdown in growth was already causing concern internationally. A political or economic crisis in any part of the world could in turn lead to a new world economic slump, the scale of which would be greater than that of the 2008 Great Recession. China will not be immune from such pressure, and this would in turn polarise the general political and economic situation inside the country. In fact, the economic and political pressure in Chinese society provoked by the outbreak is already posing unprecedented challenges for the CCP’s totalitarian regime.

Political complications

The CCP has always justified its omnipresent authoritarianism with claims that it delivers economic development. The way this new outbreak has been developing, nonetheless, is exposing in the eyes of the Chinese people that this profit-driven bureaucracy is in fact one of the main sources of the economic, political, and social crisis facing the country today.

The CCP has always justified its omnipresent authoritarianism with claims that it delivers economic development. The way this new outbreak has been developing, nonetheless, is exposing in the eyes of the Chinese people that this profit-driven bureaucracy is in fact one of the main sources of the economic, political, and social crisis facing the country today.

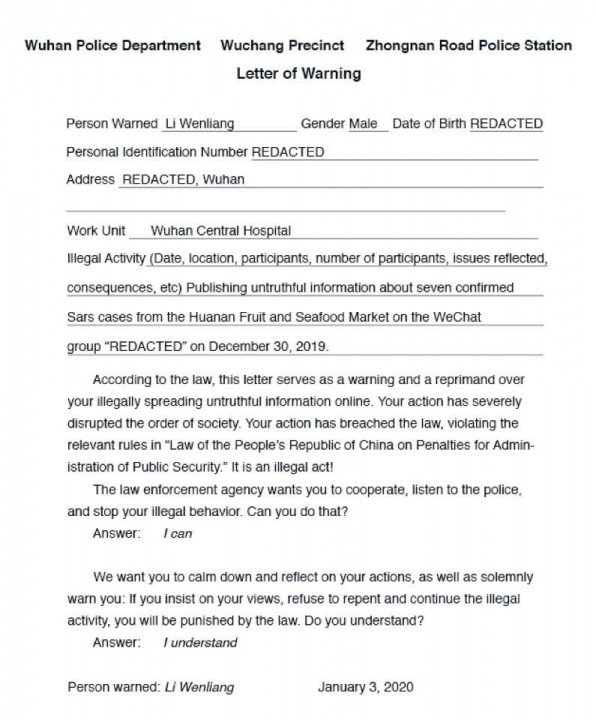

An example of this is what happened to Dr. Li Wenliang. This ordinary ophthalmologist bravely warned about the spread of a new coronavirus to his loved ones in a WeChat group in the early stages of the outbreak, but was charged and reprimanded as one of “eight rumormongers” by the Wuhan local police for doing so. As the outbreak spread, he too was infected by the virus and unfortunately later died from it on February 6th.

Li had not previously engaged in any anti-government or dissident activities. His own unfortunate fate not only reveals the arrogant and domineering attitude common to all Chinese bureaucrats, but it has also inspired many in China to raise the question of freedom of speech. According to reports published by the BBC Chinese Service on February 6th, a layer of people who regularly use the internet have been openly expressing concerns that “in the future, doctors would be reticent to sound the alarm when discovering a new disease.” Fear has turned to anger, with many demanding freedom of speech inside China, especially on the internet. On the day after the death of Dr. Li, Newslens reported: “in fact, right after the passing of Li Wenliang, the Weibo topic #IWantFreedomOfSpeech received some two million clicks and over 8,000 posts, which were immediately deleted.”

With the death of Dr. Li and the way he was treated shortly before his death, the CCP’s hamfisted method of handling important affairs was exposed to the public. The demand for freedom of speech coming from the Chinese masses under these dire circumstances is an unmistakable sign of deeply felt dissatisfaction. It also underlines the fact that the CCP bureaucracy’s control over information in key areas is what made the control of the virus in Wuhan in the early stages even more difficult.

Faced with this sudden tidal wave of public anger which cannot be put down, the CCP suddenly changed its tune. From one day to the next, Dr. Li was transformed from a “rumormonger” to a “(brave) whistleblower”, with the central government claiming that it had sent a team to Wuhan to investigate the circumstances around Li Wenliang’s treatment. Meanwhile, all official state media outlets, such as CCTV, started eulogising the bravery of Li, at the same time shifting all the blame onto the local officials in Wuhan.

In a further attempt to appear as though the central government is rectifying the situation and answering the calls for local officials to be removed, the Hubei Provincial Party Committee secretary Jiang Chaoliang was replaced by Shanghai mayor Ying Yong, while Jinan, Shandong Municipal Party Committee Secretary Wang Zhonglin was moved to Wuhan as the new party chief for the city. Several provincial and Wuhan officials have also been sacked. Ying and Wang both have police and judicial backgrounds and are seen as Xi’s factional subordinates. This move is an attempt by the central government’s to present itself to the public as the “fair and just” Party Center once again cracking down on incompetent regional officials on behalf of the people. There are indeed differences between the central and regional governments. However, everyone knows that local party chiefs are generally sponsored by someone at the top. The outgoing Hubei party chief Jiang is known to be closely tied to China’s current Vice-President Wang Qishan, who is aligned with Xi.

The fact is that the CCP’s hypocritical eulogising of Dr. Li and their shifting of blame on local officials have gone hand in hand with repression against honest individuals. An example is what has happened to citizen journalist Chen Qiushi. Chen is a well-known public intellectual inside China. As someone who had been relatively supportive of the government – he was still being accused by some overseas Chinese oppositionists of being the CCP’s “great promoter” – Chen personally witnessed Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Bill movement last year. However, he then proceeded to use his social media reach to report on the real situation instead of toeing the state media’s line. Because of this, his Weibo account was deleted.

The fact is that the CCP’s hypocritical eulogising of Dr. Li and their shifting of blame on local officials have gone hand in hand with repression against honest individuals. An example is what has happened to citizen journalist Chen Qiushi. Chen is a well-known public intellectual inside China. As someone who had been relatively supportive of the government – he was still being accused by some overseas Chinese oppositionists of being the CCP’s “great promoter” – Chen personally witnessed Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Bill movement last year. However, he then proceeded to use his social media reach to report on the real situation instead of toeing the state media’s line. Because of this, his Weibo account was deleted.

At the onset of the present epidemic, he travelled to Wuhan alone to report on the situation on the ground and interview affected residents. He then uploaded his video recordings to a YouTube channel that he opened later last year, a few of which have garnered more than one million views.

He was later confirmed by his family to have been taken away for “medical quarantine” by state security on February 7th, the day after Li Wenliang’s death. Although the regime has yet to comment on the detention of Chen Qiushi, the latter’s experience is sure to make even more Chinese people understand that Li Wenliang’s fate was not an isolated incident, but a logical consequence of the CCP’s party-state regime.

What we have to understand is that the capitalist system, as restored by the CCP itself, requires the state to enforce vicious totalitarian rule in order to block potential resistance from China’s massive working class and ensure the maximum and smoothest accumulation of capital and profits. The regime’s fear of the working class drives them to continuously deny the workers the most elementary democratic rights, such as freedom of speech, in an attempt to hold back the development of class consciousness and solidarity. Therefore, other than repression and shifting the blame, the CCP regime lacks the tools that their western ruling class counterparts enjoy, who can use bourgeois political games and reformist workers’ leaders to diffuse or misdirect ferment from below. As the capitalist system itself prepares a crisis inside China, along with the social realities exposed to the masses by the coronavirus outbreak, the Xi Jinping regime is incapable of holding back the anger that is accumulating in the depths of society, no matter how much of a strong man Xi may appear to be.

The shifting battlelines in Hong Kong

As this latest coronavirus spreads across the world, Hong Kong, neighbouring mainland China, has become a key front in containing the disease. However, the Hong Kong government has been passive in combating the outbreak. Countries neighboring China have all enacted travel restrictions to and from China, but people are still allowed to travel across Hong Kong and Guangdong via air and the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge, which leaves a loophole in Hong Kong’s containment efforts. This problem in turn is placing enormous strains on Hong Kong’s public health and medical resources, and is exerting great pressure on Hong Kong’s medical workers. In reaction to this, Hong Kong’s Hospital Authority Employee Alliance launched a one-week strike on 3 February after the government had failed to respond to their call to close the borders with the mainland. According to reports, over 4,300 medical workers in state-run hospitals refused to work during that time.

As this latest coronavirus spreads across the world, Hong Kong, neighbouring mainland China, has become a key front in containing the disease. However, the Hong Kong government has been passive in combating the outbreak. Countries neighboring China have all enacted travel restrictions to and from China, but people are still allowed to travel across Hong Kong and Guangdong via air and the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge, which leaves a loophole in Hong Kong’s containment efforts. This problem in turn is placing enormous strains on Hong Kong’s public health and medical resources, and is exerting great pressure on Hong Kong’s medical workers. In reaction to this, Hong Kong’s Hospital Authority Employee Alliance launched a one-week strike on 3 February after the government had failed to respond to their call to close the borders with the mainland. According to reports, over 4,300 medical workers in state-run hospitals refused to work during that time.

In this strike, we see that Hong Kong’s medical workers have learned to use industrial action to combat the encroachment of the CCP dictatorship and its puppet government in Hong Kong. There is a history of class struggle in Hong Kong, and we see that a tradition of strike action was revived in the recent Anti-Extradition movement and the latest medical workers’ strike, after decades of decline since the times of the anti-colonial strikes, the Hong Kong-Canton General Strike, and the struggles of 1967.

Nonetheless, although they’ve taken up class struggle methods, the Hong Kong workers still have yet to formulate demands that are clearly based on class interests and solidarity, which allows the main demand of their strike, the closing of borders, to be interpreted as xenophobic and anti-Chinese people in its aims. This gives the CCP regime another opportunity to sow distrust between the workers of Hong Kong and those of mainland China. We should remember that Dr. Li Wenliang used to believe the one-sided reporting of the CCP about Hong Kong, and supported the Hong Kong police repression of the protesters. But then, in a key moment, he courageously stepped up despite the threats from the regime, and now there are millions of Chinese people angered by how the authorities treated him. The movement in Hong Kong, instead of only being concerned with the interests of Hong Kongers, must use this opportunity to adopt genuine class struggle methods and appeal to the broader Chinese working class, adjusting their demands to ones that also benefit the affected peoples in the mainland. That way class unity can be built between the Hong Kong and mainland China workers.

In the future, we can look forward to the Hong Kong people taking up questions that go beyond the encroachment of their democratic rights by the CCP, and also understanding that Chinese and Western capitalists are both eating away their basic rights (such as high housing costs and long hours with low pay). Industrial action by Hong Kong workers will become more frequent as the crisis deepens, and the class struggle will inevitably become more intense.

The problem is that, without a class conscious workers’ leadership capable of promoting the perspective of class solidarity, the movement in Hong Kong will continue to be affected by sentiments such as anti-Chinese racism and localism. In spite of this, the ferment of the Hong Kong struggle has not dissipated, and it remains to be seen how it can place pressure upon the CCP regime further down the road. The regime is clearly aware of this potential danger, and on February 13th, they assigned Xia Baolong to be the new head of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, one of the state departments that directly liaises with the Hong Kong government. Xia is known to be a fierce enforcer of China’s policy and a factional ally of Xi Jinping. His assignment implies the CCP may take even more stern measures against the Hong Kong protests in the future.

Accident and necessity

Hegel once explained that accidents express necessity. This sudden viral outbreak – an accident – has exacerbated the existing contradictions within Chinese society. It has shone a light on the methods used by the Chinese state to silence people who are considered troublemakers. In this case, however, the “troublemaker” was an ordinary doctor who was trying to save people’s lives. Such incidents can have a huge impact on the consciousness of ordinary people. In this process, some will be asking bigger questions about the very legitimacy of the regime itself. It is part of what Trotsky referred to as the “molecular process of revolution”. As the economic crisis impacts on China, all this accumulated resentment, at some point, will surface and appear as more widespread class struggle. This is as inevitable as night follows day.

The economic crisis will undermine the legitimacy of the CCP bureaucracy, as it will no longer be able to claim that it provides jobs, wages and improved living standards. Today it has been exposed as wanting in protecting ordinary people against the outbreak of the coronavirus. Tomorrow it will be exposed as it fails to protect people against the effects of capitalist crisis.

In the struggle for their basic economic rights, the Chinese workers will also pose democratic demands, such as the right to free speech and the right to assembly. In their struggle against the bureaucracy they will also have to struggle against the capitalist system that the bureaucracy has reintroduced, and replace it with a workers’ democracy that democratically plans the economy and society. This is the only way that the people of China will finally have control over their own destiny.