Steve Jones continues his series on the history of Labour’s right wing by exploring the role of Neil Kinnock and the introduction of the “one member, one vote” system – a move designed to limit the role of the Left and the trade unions; a move that has horribly backfired with the election (and likely re-election) of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader.

Steve Jones continues his series on the history of Labour’s right wing by exploring the role of Neil Kinnock and the introduction of the “one member, one vote” system – a move designed to limit the role of the Left and the trade unions; a move that has horribly backfired with the election (and likely re-election) of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader.

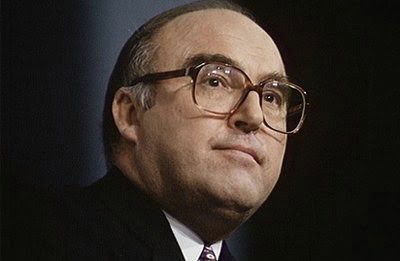

Stunned by the movement to the left inside the ranks of the Labour Party during the 1970s, and then the loss of key “moderates” to the SDP project, the right wing had turned after Labour’s election defeat in 1983 to Neil Kinnock – who was supposed to be on the “soft” left of the Parliamentary Labour Party – to become party leader and thereby now do the dirty work for them.

This Kinnock would do on both the political and organisational front. As soon as he had taken office, Kinnock announced a series of organisational “reforms”. Power was to be concentrated into a de-facto leader’s office with former student leader Charles Clarke as Chief of Staff in effect. Other opportunist cronies soon gathered around him.

One member, one vote

It was at this point that the concept of “one-member, one-vote” (OMOV) was first floated. OMOV was not intended to give the membership any more say in decision making inside the party, but rather to create a system whereby the more inert party members – or even potentially non-party members and “supporters” – could be corralled into voting for “directed” measures and candidates over the heads of the “untrustworthy“ party activists.

The ultimate aim of OMOV was to engineer a party system like that of the Democratic Party in the US whereby party “members”, as such, are just election workers and all serious decision making lies in the hands of the establishment.

For good measure, trade union influence was intended to be reduced, if not completely removed. Indeed, in the 1980s the Tories in government had pushed through a similar system for the election of senior positions inside trade unions in the hope that right-wingers would benefit over those who supported militancy.

OMOV, in one form or another, would be the aim of all Labour leaders thereafter, up to and including Ed Miliband. Its one weakness for the right wing inside Labour would be that OMOV would only work for them so long as the wider masses, or “supporters”, were not more left-wing than the members, and the members not more left-wing than the party machine. Naturally, this was a situation that Labour’s Right could not even remotely imagine ever happening…right up to the point when it did in the leadership election of 2015. Now they are talking about getting rid of OMOV, as it is no longer fit for purpose.

Capital and Labour

An attempt to start the OMOV ball rolling, with its use in the mandatory reselection of MPs, failed to even get through party conference. Kinnock, his prestige pushed back, busied himself instead with first attacking the striking miners of 1984-5, and then the Marxist-led Labour council in Liverpool.

For these acts of class treachery he would earn himself the praise of the ruling class and, in later years, a number of cushy well-paid jobs in Europe, etc.

During the Kinnock years, a new cadre of younger, more careerist right-wingers started to get manoeuvred into parliament, including a certain Tony Blair. They backed Kinnock’s push to the right, supporting the new statement of aims and values that defended the market (i.e. capitalist) system. They cheered when Kinnock attacked the Marxists around the Militant newspaper, but still demanded more. As Lewis Minkin in his 2014 book “The Blair Supremacy” noted:

“The belief that the interests of capital and labour were no longer in conflict led to a view amongst modernising radicals that Labour Party association with the unions was inappropriate for its future electoral identity.

“Around Blair, Brown and Mandelson, it was not the enhanced power of the Leader, and the unprecedented expansion of his office that was emphasised…the radicals focussed on the exceptions, qualifications and limitations to that power, especially those produced by the unions. That, to them, was the real story.” (Page 75)

They were already looking ahead to the battles to come. Interestingly, it would be the capitulation and betrayals of the “soft” left that would provide the most support to Kinnock, rather than any particular efforts on the part of the right wing, both traditional and new. The old-school machinations of established right-wingers like John Spellar, John Golding, along with groupings like Labour First, etc. would prove quite limited in the final analysis, as the new cadre of careerists begun to take form.

Meanwhile, for all the praise heaped on Kinnock by the Tory press he could not actually win an election, and so was told to fall on his sword after the 1992 defeat.

The Smith years

Kinnock’s replacement was the dour shadow-chancellor John Smith. Smith was keen to push on with OMOV. He wanted OMOV to be the system for all party elections, including that of parliamentary candidates. Linked to this would be the reduction in the size and involvement of the union “block” vote. The right wing around Blair would argue for its total removal as an “essential” measure.

Kinnock’s replacement was the dour shadow-chancellor John Smith. Smith was keen to push on with OMOV. He wanted OMOV to be the system for all party elections, including that of parliamentary candidates. Linked to this would be the reduction in the size and involvement of the union “block” vote. The right wing around Blair would argue for its total removal as an “essential” measure.

In early 1993, Mandelson publically demanded a more far-reaching programme of changes inside the party (see Minkin, page 92), even though there was at this time little actual support for such a reactionary transformation from inside the ranks of the party itself.

Smith came forward with a watered-down version of OMOV to present to the party’s annual conference in 1993. However, he was getting little support from either the CLPs or, in particular, the trade unions. The union officials needed a classic get-out to ensure that Smith could avoid defeat without exposing the uselessness of the trade union leaderships to their own members, who had opposed OMOV and the cutting back of the union vote.

The answer was to link OMOV to the question of all-women shortlists. This proposal had great appeal to the petty-bourgeois elements inside the party and enabled key delegations to safely switch their vote to support the OMOV proposals or at least to abstain. Even then it required a key intervention at conference from another “soft” left – John Prescott – to finally get the vote through.

The right wing was both relieved and angry: relieved that the Left advance in the party had been reversed; but angry that total OMOV had failed to make any headway. Trade union involvement in key elections and decision-making would remain via a “college voting system” and the continued block vote at conference, as Prescott had made very clear in his conference speech.

Blair, in particular, now demanded more and had even raised the idea of key decisions being agreed by a “plebiscite mechanism” or referendum (a classic device of Bonapartist rulers, by the way) rather than by conference or the newly-formed Policy Forum.

Smith, however, had won his victory and showed little interest in further changes, preferring to concentrate on the chaos inside the Tory Party, now mired in corruption scandals and reeling from the economic downturn. It seemed increasingly likely that the John Major Tory government would be thrashed at the next general election, propelling John Smith into Number Ten at the head of a majority Labour administration.

But it was not to be for Smith. On the morning of 12th May 1994, John Smith keeled over in his Barbican flat with a fatal heart attack. His body had hardly hit the bathroom floor before the right-wing media were pushing for the “obvious” successor: Tony Blair.