The right-wing media is full of stories about the “threat” of left-wing “entryism” inside the Labour Party. But the Labour right wing have themselves been well organised and financed – not just in recent years, but over many decades. In this article, Steve Jones looks at the murky history of the Labour right, and why they present a barrier to a socialist transformation of society.

With the formation of Momentum, tasked with the job of defending and organising the Corbyn movement, there has been much shouting from the ranks of the establishment about the “dangers” of the Left “organising”, and in particular the possibility of the de-selection of Labour MPs taking place. Nothing seems to so enrage right-wing Labour MPs as the threat to their careers. Tom Watson, the deputy Labour leader, meanwhile, has raised a hue-and-a-cry about Trotskyists and “entryism”.

This is apparently an “affront” to British democracy and something that must be fought against by all means necessary. In this context, the summer coup attempt against Corbyn by a majority of Labour MPs (using a plan leaked to the Telegraph several months earlier), and the enforced leadership election now taking place, shows where the priorities of these people really lies. If only these people were to put the same energy into fighting the Tories and their rotten policies.

In all their talk about the “dangers” of a growing Left movement, however, they somehow neglect to mention that the Labour right wing have themselves been well organised and financed not just in recent years, but over many decades. Capitalist entryism into the structures of the labour movement has been a long-established fact.

Fifth Column

Anyone attending the last Labour Party conference would have been struck by the number of fringe meetings organised by various bodies such as the misnamed Progress, the Policy Network, and so on. All seemed to have the same motley crew of right-wing Labour MPs (past and present), journalists and assorted Blairite “experts” such as John McTernan speaking, all with the single aim of undermining and sniping at Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership.

Interestingly enough, nearly all of these meetings enjoyed some form of financial support from companies and special interest organisations. Now we have a new wave of similarly shady right-wing groups – such as Labour First, Saving Labour, and Labour Tomorrow – being formed to lead the Blairite counter-reaction inside the Labour Party. In the PLP, we also have the fifth column of the “Labour For The Common Good” group.

Over the last few years, many questions have been asked about groups like Progress – “the party within a party” – and the role it and others have played in organising right-wing forces within Labour. Whereas the Left have traditionally been queasy if not down right naïve about organising in return, preferring instead to believe that we are all going in the same direction and have the best interests of Labour at heart, the truth is that the right-wing within Labour has been organised for decades, operating to a very different agenda.

With unlimited resources they have plotted and recruited to their ranks layers of the most careerist and ambitious, often from the field of student politics, in order to bolster their ideas within the movement. John Mann, Mike Gapes and Charles Clarke are just three of many names that spring to mind here. Blairite apologist Luke Akehurst let the cat out of the bag when, in a blog entry from 2011, he outlined how in 1996 he joined the right-wing Labour First group, “largely because John Spellar made the effort to reach out and recruit me…” Spellar is one of those who has been most vocal in recent months in attacking Corbyn.

Akehurst makes clear that his priorities were to support the right-wing in Labour on issues such as nuclear arms and NATO. He goes on to note that the real history of Labour’s right-wing should be remembered: “the heavy lifting had already been done by the Old Right around the MPs in Labour Solidarity, the union leaders and political officers in the St Ermin’s group and the newsletter Forward Labour.”

So what is the real history of the Labour right-wing? How were they organised, and who funded it? What side were (and are) they really on?

The people “we” support

Much of this story would have remained hidden from view for many years, had it not been for an article on the subject, commissioned by The Sunday Times in 1972, but rejected by editor Harold Evans because “…these are the people we support!”

The “banned” article, written by Richard Fletcher, would instead go on to be reproduced in a number of magazines, pamphlets and books, ironically achieving a far wider distribution as a result. In the article, Fletcher outlined how after decades of iron control inside the party by officials and trade union leaderships, fissures began to show themselves inside the party between Left and Right after the Second World War.

The American establishment in general, and the CIA in particular, were already looking with concern at leftward movements in the mass organisations in Europe and started to take a particular interest in the British Labour Party. Labour’s right-wing had started to mobilise around an anti-Marxist publication called Socialist Commentary.

In 1947, a number of leading Labour right-wingers became contributors and the journal was turned towards targeting the Left within Labour. A number of Labour’s Right also became involved with the American-based anti-communist magazine New Leader. In 1950, the Congress of Cultural Freedom (CCF) was launched to “defend” the West and immediately attracted a number of Labour figures in Britain to its ranks.

One of those was Anthony Crosland, who under CCF guidance wrote the now-forgotten bible of reformism The Future Of Socialism, published in 1956, which sought to outline how class struggle was being replaced by never-ending plenty under which reforms would now be the only way forward. The CCF magazine Encounter started to attract around it a number of leading Labour figures, including Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell.

Oddly enough, no one sought to question how all this was being financed. The right wing felt in a strong position, armed with the might of the party machine. In 1955 they attacked Tribune and tried to expel Aneurin Bevan for disloyalty against Attlee. However, by one vote on the NEC, they were defeated on this.

Clause IV

The right wing bided their time and in 1960, straight after the general election defeat of 1959, they decided to move. The aim would be getting rid of Labour’s Clause IV – the historic commitment to public ownership.

The right wing bided their time and in 1960, straight after the general election defeat of 1959, they decided to move. The aim would be getting rid of Labour’s Clause IV – the historic commitment to public ownership.

Well-funded surveys were produced “proving” that nationalisation was unpopular and a campaign by MPs was launched to move the party to the Right. Armed with a mysterious “windfall” of funds, a 25,000 print run of a manifesto outlining their position was produced and offices and staff were taken on for the “Campaign for Democratic Socialism.”

They failed over Clause IV, but another target was already in front of them, as Labour had moved towards a neutralist programme over nuclear weapons at the 1960 party conference. A massive campaign was launched, “without a single subscription paying member”, to reverse the decision – which indeed happened the following year – and re-establish the grip of the Right within the party.

In later years, it would become clear that these assorted campaigns and publications were being heavily funded by a variety of American conduits, all with the aim of ensuring that the Labour Party stayed on board for the aims of the US government and capitalism.

Although the names of the various groups would change in the following decades, the general thrust of this “penetration” by US interests would not. In a speech made by Robin Ramsey in 1996 about this very subject, he notes that “…The US ran education programmes and freebie trips, for sympathetic Labour movement people. Hundreds, maybe thousands…had these freebies.” The links between the Right in Labour and the US establishment have remained so strong over the years that Ramsey suggests we should call them “the American Tendency”; and by American we don’t mean those millions of workers and youth who are daily fighting the system in the US.

For example, notes Ramsey, Peter Mandelson had by 1976 “become Chair of the British Youth Council (which) as the British section of the World Assembly of Youth (had been) set up and financed by MI6 and then taken over by the CIA in the 1950s” before later returning to MI6 control.

All manner of bodies have been brought into play to influence promising figures inside the Labour movement. For example, as journalist John Pilger noted in 2003: “Five members of Blair’s first cabinet, along with his Chief of Staff, Jonathan Powell, were members of the British American Project for a Successor Generation” – a body launched by Ronald Reagan and funded by right-wing oil baron J. Howard Pew, with the aim of ensuring that American foreign policy would be accepted by social-democratic parties abroad.

To give another example, Jim Murphy, Scottish Labour’s former leader and arch-Blairite, has been – along with 15 other Labour MPs – on the political council of the Henry Jackson Society. The HJS is a US-based right-wing, anti-Muslim organisation founded as a neo-conservative think-tank in 2005.

A thousand threads

Even if you ignore the American (and British) state influence over the actions of Labour’s right-wing, there is clear evidence that these people were already more than happy enough to continue to organise against the Left inside the movement over the years. They owed their allegiance to capitalism one-hundred percent.

Recent decades have seen a rise in funding of the Labour Right from British capitalists, looking for an alternative “safe” option to their natural allies, the Tories. Whereas in the past the right wing would recruit from Labour movement officialdoms, more recently they have been able, often via the student movement, to recruit from more class-friendly layers – people who are already tied by a thousand threads to the establishment. This has been reflected in a decline in numbers of Labour MPs and candidates from working class backgrounds – something that must now be reversed.

Above all else, the Right in Labour rested, in the post-war years, on the boom in the economy. When “normal service” was resumed from the 1960s onwards, crisis and cuts returned to the economic scene and that basis of support was removed. Reformism with reforms would be replaced by reformism without reforms. With a resultant shift to the Left inside the movement, the traditional Labour right-wing found themselves being pushed back.

After decades of iron control, the end of the 1960s had started to see a shift in the fortunes of Labour’s right wing. Up to then they had been able to operate in a well-organised (and financed) fashion, backed by a ruthless and single-minded party machine.

In the 1950s, although they had failed to expel Anuerin Bevan and the Bevanites, they had been able to prevent known left-wingers from becoming Labour candidates.

Labour officials at Transport House (the then party HQ) reviewed regular briefings from the Special Branch and reactionary groups like Common Cause to identify any troublemakers who may have shown their faces in local parties.

In 1962, the Labour leadership attempted to extend control over the party ranks, backed by such Witchfinder Generals as Sara Barker, by toughening up the use of the proscribed list of organisations that party members could not associate with. An attempt to expel all Labour Party members who were down as supporting a world disarmament congress via the British Peace Council – a proscribed organisation – backfired when it became clear that amongst those being threatened was Bertrand Russell, who sharply rejected the letter sent by Transport House telling him to withdraw support for the congress. The legal basis for expulsion was also being challenged.

Arising from this, the NEC attempted at the 1962 Labour conference to tighten up the rules in order to get round any legal challenge and widen proscription to include “guilt by association”. Delegates overwhelmingly rejected the rule changes.

In passing, it is interesting to note that whereas today the Labour Right (or “moderates” as they like to style themselves) are at great pains to demand freedom of speech and the right to attack the Labour leader, there was a time when such “rights” were considered expellable offences. The double standards of these people are all too clear, as we have again seen in the current leadership election, with supporters of Corbyn being expelled on spurious grounds and with the sort of contempt for natural justice which recalls Stalin’s purges in Russia.

Reselection

The 1960s and 70s would see the iron grip of the Right in Labour further loosened, not least because the post-war boom on which reformism rested was clearly coming to an end, never to return on the same scale again.

The 1960s and 70s would see the iron grip of the Right in Labour further loosened, not least because the post-war boom on which reformism rested was clearly coming to an end, never to return on the same scale again.

The old right wing in the unions were starting to be pushed out of their positions as industrial militancy returned to the fore. New social movements were starting to affect even the Labour Party.

By 1968, Sara Barker – the last of the old dinosaurs – had been replaced by Ron Hayward as National Agent. The proscribed list had fallen into disuse (to be abolished in 1972) and central control over the selection of party candidates was wound back – for the time being anyway.

Although some of the old guard still demanded that action be taken against the Left, the more far-sighted of their number decided to play the waiting game.

Where right-wing Labour MPs were deselected, the NEC now took the position that they would not intervene if the CLP had fully followed the rules – the “Mikado doctrine”.

This approach would be tested in 1975 by the Reg Prentice case. Prentice, Labour education secretary and MP for Newham North-West, had shifted so far to the right that his local party had decided that things had gone too far and voted for him to retire at the next election. Prentice protested and presented himself as being the victim of a “Marxist plot”.

However, the NEC, which now had a clear Left majority, supported the local party and a year later Prentice had defected to the Tories (showing his true face), later serving as a junior minister under Thatcher. In the following years other right-wing Labour MPs would also get the boot, including the racist Frank Tomney in Hammersmith North and the aging Sir Frank Irvine in Liverpool, Edge Hill.

The Social Democratic split

A key question then, as now, was clearly the demand for the mandatory reselection of MPs. A growing mood existed in the party ranks, boosted by the above-mentioned cases and by the failures of Labour in office between 1974 and 1979. One-in-eight of all resolutions submitted to the party’s 1977 annual conference was on the subject. After several years of delaying tactics and dodgy vote fiddles to keep the issue from being voted through, the measure was finally passed at the 1979 party conference.

In 1980, the election of the party leader and deputy was moved away from the Parliamentary Labour Party and into the hands of an electoral college comprising the PLP together with the unions and constituency parties.

This was too much for a section of the parliamentary Labour right-wing. In January 1981, a number defected to form the Social Democratic Party (SDP), which immediately got huge support from the Tory press, who saw the opportunity to at least split the Labour vote at the following general election, if not replace it.

The SDPs sole achievement was to help stop Labour winning the 1983 general election, which resulted in a huge Conservative majority even though the Tory vote actually fell. Ironically, Labour’s vote was still high enough that had Ed Miliband been able to match it in the 2015 election then Labour would have won. Later on, as support waned, the SDP dissolved into the Liberal Party to form the Liberal Democrats, with a number of their ranks sneaking back into Labour as part of the Blairite clique.

Warning from history

Many of the SDP traitors had been part of the Manifesto Group in the PLP, formed by the sinister Dickson Mabon in 1974 with the specific aim of fighting the Left. Those right-wingers who had remained with Labour now re-organised around a new grouping (to replace the discredited Manifesto Group) called Solidarity, which was again well financed. It would be noted by their supporters that they would prove far more ruthless at organising to grab positions in the party than was the case with the Labour Left. This is as much a warning for today as was the case then.

On the trade union front, the right wing was also re-organising to regain their traditional influence both over their own organisations and over the Labour Party. They met in 1981 behind closed doors at the posh St. Ermin’s Hotel (from which they would take their name) to start the plotting.

Quickly the right wing begun grabbing union positions on Labour’s NEC, and by 1982 had delivered a right-wing majority to that body. Again it should be noted that Labour’s right wing have never had any problems about organising themselves (and often in secret), whilst at the same time hypocritically harping on about how bad it is that the Left is also organising.

Enter Kinnock

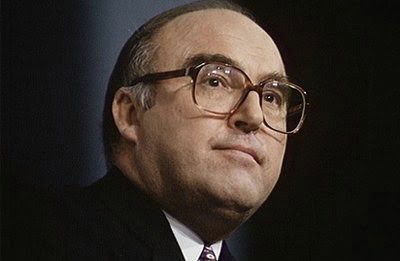

After Labour’s election defeat in 1983, the party elected Neil Kinnock as leader, replacing Michael Foot. Although on paper a soft-left, Kinnock would quickly move to the right once in office. Lewis Minkin, in his 2014 book “The Blair Supremacy”, notes that “… a growing mutual appreciation had united Kinnock with the mainly right-wing trade union group”. Kinnock’s betrayal of the miners’ strike was just the most visible indication of this process. Under Kinnock the PLP would also move to the right.

After Labour’s election defeat in 1983, the party elected Neil Kinnock as leader, replacing Michael Foot. Although on paper a soft-left, Kinnock would quickly move to the right once in office. Lewis Minkin, in his 2014 book “The Blair Supremacy”, notes that “… a growing mutual appreciation had united Kinnock with the mainly right-wing trade union group”. Kinnock’s betrayal of the miners’ strike was just the most visible indication of this process. Under Kinnock the PLP would also move to the right.

This period also saw a general shift to the right on the part of a layer of so-called “soft lefts” as they sought to accommodate themselves to the new situation. The Labour Co-ordinating Committee was just one such “left” body to slide to the right, and would in time provide additional support for Blairism before being wound-up after the 1997 general election.

Needless to say, the Tory press were more than happy to support the Labour Right as part of the fight against the “Loony Left”, as they liked to put it. With the failure of the SDP, regaining control of Labour was essential for the Establishment.

Under Kinnock, the party machine was also restructured to give more “support” for the party leadership, and it was during this time that the likes of Peter Mandelson (as Director of Communications) started to exert more influence. Minkin notes that under Mandelson, “…the image of rising stars Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were boosted, but competitors…were disadvantaged or even undermined.”

To widen the influence of the right-wing inside the party ranks, Labour First was formed in 1988, described by some as being a “pre-Blairite” group.

Minkin records that by 1990 a senior party official was already telling him that the next step would be to “get rid” of the unions. The 1990s would see this aim pushed into the open, as Labour’s right-wing now sought to complete what the SDP in the 1980s had failed to do.

Stunned by the movement to the left inside the ranks of the Labour Party during the 1970s, and then the loss of key “moderates” to the SDP project, the right wing had turned after Labour’s election defeat in 1983 to Neil Kinnock – who was supposed to be on the “soft” left of the Parliamentary Labour Party – to become party leader and thereby now do the dirty work for them.

This Kinnock would do on both the political and organisational front. As soon as he had taken office, Kinnock announced a series of organisational “reforms”. Power was to be concentrated into a de-facto leader’s office with former student leader Charles Clarke as Chief of Staff in effect. Other opportunist cronies soon gathered around him.

One member, one vote

It was at this point that the concept of “one-member, one-vote” (OMOV) was first floated. OMOV was not intended to give the membership any more say in decision making inside the party, but rather to create a system whereby the more inert party members – or even potentially non-party members and “supporters” – could be corralled into voting for “directed” measures and candidates over the heads of the “untrustworthy“ party activists.

The ultimate aim of OMOV was to engineer a party system like that of the Democratic Party in the US whereby party “members”, as such, are just election workers and all serious decision making lies in the hands of the establishment.

For good measure, trade union influence was intended to be reduced, if not completely removed. Indeed, in the 1980s the Tories in government had pushed through a similar system for the election of senior positions inside trade unions in the hope that right-wingers would benefit over those who supported militancy.

OMOV, in one form or another, would be the aim of all Labour leaders thereafter, up to and including Ed Miliband. Its one weakness for the right wing inside Labour would be that OMOV would only work for them so long as the wider masses, or “supporters”, were not more left-wing than the members, and the members not more left-wing than the party machine. Naturally, this was a situation that Labour’s Right could not even remotely imagine ever happening…right up to the point when it did in the leadership election of 2015. Now they are talking about getting rid of OMOV, as it is no longer fit for purpose.

Capital and Labour

An attempt to start the OMOV ball rolling, with its use in the mandatory reselection of MPs, failed to even get through party conference. Kinnock, his prestige pushed back, busied himself instead with first attacking the striking miners of 1984-5, and then the Marxist-led Labour council in Liverpool.

For these acts of class treachery he would earn himself the praise of the ruling class and, in later years, a number of cushy well-paid jobs in Europe, etc.

During the Kinnock years, a new cadre of younger, more careerist right-wingers started to get manoeuvred into parliament, including a certain Tony Blair. They backed Kinnock’s push to the right, supporting the new statement of aims and values that defended the market (i.e. capitalist) system. They cheered when Kinnock attacked the Marxists around the Militant newspaper, but still demanded more. As Lewis Minkin in his 2014 book “The Blair Supremacy” noted:

“The belief that the interests of capital and labour were no longer in conflict led to a view amongst modernising radicals that Labour Party association with the unions was inappropriate for its future electoral identity.

“Around Blair, Brown and Mandelson, it was not the enhanced power of the Leader, and the unprecedented expansion of his office that was emphasised…the radicals focussed on the exceptions, qualifications and limitations to that power, especially those produced by the unions. That, to them, was the real story.” (Page 75)

They were already looking ahead to the battles to come. Interestingly, it would be the capitulation and betrayals of the “soft” left that would provide the most support to Kinnock, rather than any particular efforts on the part of the right wing, both traditional and new. The old-school machinations of established right-wingers like John Spellar, John Golding, along with groupings like Labour First, etc. would prove quite limited in the final analysis, as the new cadre of careerists begun to take form.

Meanwhile, for all the praise heaped on Kinnock by the Tory press he could not actually win an election, and so was told to fall on his sword after the 1992 defeat.

The Smith years

Kinnock’s replacement was the dour shadow-chancellor John Smith. Smith was keen to push on with OMOV. He wanted OMOV to be the system for all party elections, including that of parliamentary candidates. Linked to this would be the reduction in the size and involvement of the union “block” vote. The right wing around Blair would argue for its total removal as an “essential” measure.

Kinnock’s replacement was the dour shadow-chancellor John Smith. Smith was keen to push on with OMOV. He wanted OMOV to be the system for all party elections, including that of parliamentary candidates. Linked to this would be the reduction in the size and involvement of the union “block” vote. The right wing around Blair would argue for its total removal as an “essential” measure.

In early 1993, Mandelson publically demanded a more far-reaching programme of changes inside the party (see Minkin, page 92), even though there was at this time little actual support for such a reactionary transformation from inside the ranks of the party itself.

Smith came forward with a watered-down version of OMOV to present to the party’s annual conference in 1993. However, he was getting little support from either the CLPs or, in particular, the trade unions. The union officials needed a classic get-out to ensure that Smith could avoid defeat without exposing the uselessness of the trade union leaderships to their own members, who had opposed OMOV and the cutting back of the union vote.

The answer was to link OMOV to the question of all-women shortlists. This proposal had great appeal to the petty-bourgeois elements inside the party and enabled key delegations to safely switch their vote to support the OMOV proposals or at least to abstain. Even then it required a key intervention at conference from another “soft” left – John Prescott – to finally get the vote through.

The right wing was both relieved and angry: relieved that the Left advance in the party had been reversed; but angry that total OMOV had failed to make any headway. Trade union involvement in key elections and decision-making would remain via a “college voting system” and the continued block vote at conference, as Prescott had made very clear in his conference speech.

Blair, in particular, now demanded more and had even raised the idea of key decisions being agreed by a “plebiscite mechanism” or referendum (a classic device of Bonapartist rulers, by the way) rather than by conference or the newly-formed Policy Forum.

Smith, however, had won his victory and showed little interest in further changes, preferring to concentrate on the chaos inside the Tory Party, now mired in corruption scandals and reeling from the economic downturn. It seemed increasingly likely that the John Major Tory government would be thrashed at the next general election, propelling John Smith into Number Ten at the head of a majority Labour administration.

But it was not to be for Smith. On the morning of 12th May 1994, John Smith keeled over in his Barbican flat with a fatal heart attack. His body had hardly hit the bathroom floor before the right-wing media were pushing for the “obvious” successor: Tony Blair.

The sudden death of Labour leader John Smith early on 12th May 1994 came as a shock to many. However, this did not stop a massive establishment spin operation from getting underway within just a few hours of the mid-morning news announcement. Its purpose was simple: to present Tony Blair as being “the only possible choice” as the next leader. Press cronies and ambitious MPs had been talking up Blair for some time now and clearly they felt that this was his best chance to grab the position without further delay.

So blatant was the campaigning for Blair that even Thatcher, when door-stepped at lunchtime by journalists about the forthcoming contest, felt obliged to remind the press that a man had just died. This naked lust for power by Tony Blair and the so-called “modernisers” who would later form the core of New Labour summed up everything you could later say about the Blair years.

Compared to the detailed interrogation by the press that accompanied Corbyn’s leadership campaigns, the Blair campaign of 1994 was treated as a virtual coronation by the establishment, and with minimal opposition (not to mention considerable financial support) Blair was duly elected as leader albeit with 57% of the vote.

Politics and plotting

In any serious assessment of Blair and the New Labour years it is necessary to concentrate on the politics and the shift towards neoliberalism on the part of the party leadership, both in opposition and then in office.

However, as outlined in previous articles in this series on Labour’s hidden history, there is value also in looking at the organisational aspects of Labour’s right wing over the years. These people are the first to complain about attempts by the Left to organise. Yet the right wing have a long and dishonourable history of plotting, fixing, fiddling and otherwise manoeuvring within the movement to get what they want by fair or (more often than not) foul means.

Lewis Minkin’s book on Blairism and the Party, The Blair Supremacy (Manchester University Press, 2014), is both the most recent and the most detailed study of this period. According to Minkin, the New Labour project (as they called it) was driven by a “group of three – Blair, (Gordon) Brown, and (Peter) Mandelson – plus Alistair Campbell and Philip Gould…their greatest unity was in the negative appraisal of the party including and particularly its affiliated unions and its associated collective body – the TUC.” (page 117)

The task for the Blairites was to take immediate control of the Labour Party machine and reshape it from top to bottom. As Minkin observes “… the takeover of the party by this small majority was quietly and sometimes boastfully acknowledged to be a coup d’etat over the party.” (page 118)

All power was to be concentrated in the Leader’s office and Blair would now decide who occupied senior party positions as part of what Minkin correctly called “…a comprehensive interlocking managerial machine operating under the guidance of the leader’s office and headquarters…there was an unprecedented build-up of the role of leader, not least in its dismantling of checks and balances which limited his role…” (page 136). Organisationally, the first person to get the boot was Party general secretary Larry Whitty, with five successors coming and going over the next 12 years under Blair.

Political re-alignment

Blair became obsessed with the idea of a new political re-alignment with the Lib-Dems as part of the process of forming a “new progressive alliance” along pro-capitalist lines. Naturally the logic behind this was the usual right-wing one of the so-called decline of the “traditional working class” as against the rising numbers of middle and even upper classes.

Blair became obsessed with the idea of a new political re-alignment with the Lib-Dems as part of the process of forming a “new progressive alliance” along pro-capitalist lines. Naturally the logic behind this was the usual right-wing one of the so-called decline of the “traditional working class” as against the rising numbers of middle and even upper classes.

This is an analysis which has no basis in fact, but is still being used today by the Labour Right to attack Corbyn. For good measure, Blair also ordered closer links with big business and the City of London – an extension of the “prawn cocktail offensive” of 1992 which in the end had proved pretty ineffectual in garnering votes.

Blair knew that the first and most critical task was to shift the Parliamentary Labour Party to his way of thinking. Given the tendency towards careerism inside the PLP this would not be difficult.

However, Blair wanted people he could trust and who he knew; who had gone to the same schools and universities and were linked together as part of a shared network. Indeed, the opportunist swamp of student politics would provide a ready source of people keen on career in Westminster, who allegiance would depend merely on which party or leader was on the up.

Blairite hypocrisy

Over the next two decades this process would be put into effect with a vengeance, both in parliamentary candidate selections and the appointment of senior party positions.

The right-wing campaigning structures also had an overhaul, with Progress being formed in 1994 as a well-funded Blairite fan club.

For good measure SDP traitors were encouraged to re-join the party. In contrast to today’s purge of the Left from the Labour Party, no attempts were made here by Labour bureaucrats or “Compliance Units” to stop these people from joining or re-joining because of past misdeeds. Later, even Tories would be allowed to cross right over if it suited Blair. Again, we see clearly how there is also one rule for the Right and another for the rest of us.

Blairite backers like Mandelson and Roger Liddle, in their now hilarious book The Blair Revolution (Faber and Faber 1996), made every effort to present Labour under Blair as a “new, modern” party, like the SDP but with a “more rounded” approach – but still pro-capitalist in reality.

However, the establishment – which understood the class forces and their relationship to the Labour movement better than the likes of Blair, Mandelson and Liddle did – still needed convincing that Blair was serious about creating a new party, far more sympathetic to big business. Blair needed a symbol of his fealty to the establishment – and he found it with the campaign to ditch Clause IV.

The purpose of this series of articles has been to show how Labour’s right wing has constantly used its position over the years – and indeed decades – to organise and plot, and as a result undermine the democratic processes of the party for their own (and capitalism’s) benefit.

Certainly some of their number may well once have believed that they were acting in the general interests of the working class, and that through reformism there would indeed be a parliamentary road to socialism that would arrive at its destination at some point in the dim and very distant future.

However, in recent decades, as the system has stopped offering reforms and instead demanded counter-reforms, this slender and naive strand has all but disappeared, to be replaced by an army of blatant careerists who in essence are no different from the Tories. The rise of this capitalist cadre would be accelerated as never before under Tony Blair.

Clause IV

Having gained control of the Labour Party leadership in 1994 and having set about pulling all decision making in under its office, Tony Blair started looking around for a symbol which could prove in the eyes of the ruling class that he was loyal to capitalism and would be able to drag the party behind him. He found this in the decision to get rid of Clause IV of the party constitution. This historic commitment to public ownership and socialism had long been seen as a stone in the right wing’s shoe.

Using all the resources of the party machine – and by neglecting to allow any amendments to the new Blairite clause – the removal of Clause IV was pushed through in 1995. Even so, three-quarters of party members refused to vote in the ballot. There was huge opposition inside the ranks of the movement, despite the support for the new clause on the part of many MPs, trade union leaders and, of course, the Tory media.

A draft manifesto, reflecting Blairite Tory-lite policies, was then drawn up and presented to party conference without the chance to amend it or even vote for or against the document. It was then put to the party membership, again without the chance to amend. With no other choice, members voted in favour in what one journalist called a “take it or take it” ballot. The concept of Partnership In Power (as it was surreally called) would quickly be seen as rather one-sided. Under Blair the only partnership would be with capitalism.

Concentrating power

After the 1997 Labour victory that put Blair in Number 10, the process of concentrating all power into the leader’s office was sped up. The NEC policy committee was formed, but never met even though the NEC had ceded power over policy to this body. The national conference was reduced from five to four days, in effect becoming a trade fair with a few speeches tacked on. Party structures began to be wound down, to be replaced with formless “all members” meetings. Above all else, all decisions were now to go through the leader’s office and reflect “what Tony wants”.

The Parliamentary Labour Party was also to be made more compliant. Firstly, by fast-tracking new, young apolitical careerists into safe and winnable seats (many of the most anti-Corbyn Labour MPs would gain their seats this way). Secondly, by working to get rid of or neutralise those Labour MPs who were seen as being too left or not “on board” with New Labour. Plans were laid to try and deselect Labour MPs who did not toe the line – an irony given recent events – or otherwise ensure that local parties would be “prompted” to put pressure on these troublemakers.

Of course, the question of breaking the party links with the trade unions – an obsession of many of the most ardent Blairites – would remain on the table, with Stephen Byers stating in 1996 that any industrial problems under a Labour government might well act as the trigger. Byers was already anticipating that New Labour and Blair’s close links with big business and various rich chums would create problems down the line with the unions.

By the time Blair was pushed out of office, to be replaced by his arch-enemy, Gordon Brown (who successfully manoeuvred as sole candidate to ensure that there was no challenge allowed to him in a leadership election – no moaning from right-wing Labour MPs here, it should be noted), the whole illusion of party democracy had fallen into total disrepair. So far as most party members were concerned, the establishment decided everything.

A crude attempt to stop Ken Livingstone from being the Labour candidate for London Mayor resulted in him standing as an independent and gaining the support of most London party activists and Labour voters, winning easily. Many Labour members, meanwhile, had openly opposed the Iraq war. However, other opportunities to show revolt were somewhat scarce.

Parachuted in

Under Brown, and to a certain extent Ed Miliband also, the rigging of the parliamentary candidate selection system continued, with only a few local parties resisting the parachuting in of favoured faces. The main right-wing pressure group inside Labour – the misnamed “Progress” – had become a well-funded job centre for establishment careerists looking for advancement.

For Blair and Brown, the aim was to finally crush the opposition of the party activists by extending OMOV to create a system whereby members could be swamped by the media-controlled votes of wider supporters. It would be “red” Ed Miliband who would finally push the plan through at a special conference. The block votes of the unions would be downgraded, with individual union members having a direct vote for party leader along with registered supporters. Blairites like Mandelson were ecstatic.

As explained previously, however, things would take a very different path to that predicted by the Blairites, with the shock election of Corbyn to replace Miliband in the 2015 leadership contest following Labour’s defeat at the general election.

Complete the Corbyn revolution!

It is in this context that we see the current anger of the careerist Labour MPs, who have experienced a revolt of the membership against them, with the re-election of Corbyn as Labour leader.

For years the right wing has relied on crushing opposition and stopping real debate to ensure a smooth career path at Westminster and beyond. They are closer to their pals in the Tory Party than to the working class and will never be reconciled to having to fight for socialism – a system that is directly opposed to their world of privilege and class collaboration.

For the movement behind Corbyn, the task of clearing this layer out of their positions must now be a central demand. The party membership, which slumped under Blair, Brown and Miliband, leaving a party that was dead on its feet, has revived under Corbyn.

The barrier now facing the movement is the old Blairite wreckage seeking to reverse the Corbyn revolution. This barrier must be removed.