In the age before digital photography, Flickr accounts, and home printers, people took their rolls of film to chemists to be developed and glossy prints made. In many cases, this was not done by the chemist as such, but by outside firms who would be sent the film rolls by post, with the prints coming back to the shop a few days later. One such firm in the 1970s was Grunwick, trading under such familiar names as Bonusprint, which occupied a shabby factory near Willesden Green in North-West London.

Leafy Dollis Hill and Willesden Green, sitting in the suburban London Borough of Brent, was hardly a centre of class struggle; yet for over a year in 1976-77, this part of London would become central to the rise of union militancy and the fight against rogue employers. There was nobody around at the time that would not become aware of the historic struggle at Grunwick and what was at stake as workers went on strike for their rights.

Forty years later, the strike at Grunwick has been marked by a small but interesting exhibition “Grunwick 40: We are the lions”, being held at the Willesden Green Library until 26 March 2017. The title refers to a statement by one of the strike leaders, Jayaben Desai, who said: “What you are running is not a factory, it is a zoo. But in a zoo there are many types of animal. Some are monkeys who dance on your fingertips. Others are lions who can bite your head off. We are the lions, Mr. Manager.”

Dickensian conditions

The Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories wasn’t a zoo, of course, but it was a miserable sweatshop with working conditions that Charles Dickens would have easily recognised. Pay was low, hours were long, and overtime could be enforced at any time. The mainly-Asian workforce was un-unionised and subject to all manner of petty restrictions by management, not dissimilar to those we have seen recently in zero-hour setups like Sports Direct. Conditions had been made worse over the summer of 1976 by the never-ending heatwave that had lasted through most of the season without a break, leading to the Labour government appointing a Minister for Drought.

On 20th August, a Grunwick worker, Devshi Bhudia, was sacked for “working too slow”. Three other workers walked out in support, and management then sacked another worker, Jayaben Desai, without reason. The five, together with Jayaben’s son, picketed the site and agreed to join a union, APEX (now part of the GMB), known for its right-wing leadership. A previous attempt in 1973 to get a union presence in the factory via the TGWU had failed. This time the six were able to get other workers to join the union and walk out on strike in support of the sacked employees and for better conditions.

The strike was made official, and support for the workers begun to grow. The fact that the Grunwick management was refusing all talks and attempting to halt union recognition just added fuel to the fire.

One thing soon became clear: that the Grunwick strikers were gaining the full support of the wider labour movement and the local community. This was in sharp contrast to the dispute a few years earlier in 1974 at the Imperial Typewriters site in Leicester, where there was a clear racial divide being fomented between white workers and the Asian workforce out on strike. The factory here did have union recognition – indeed it was a closed-shop – but the lay union officials were hostile to the Asian workers, a situation made worse by the large vote gained by the Fascist National Front in the recent elections. The officials dragged their feet and hid the fact that they had colluded in pay differentials for white and non-white workers. This bitter dispute had led some to erroneously raise the question of separate union organisation for non-white workers. The solidarity shown in the Grunwick dispute would go a long way to burying that idea and underlining the importance of workers of all ethnicities and nationalities uniting in common struggle.

Solidarity

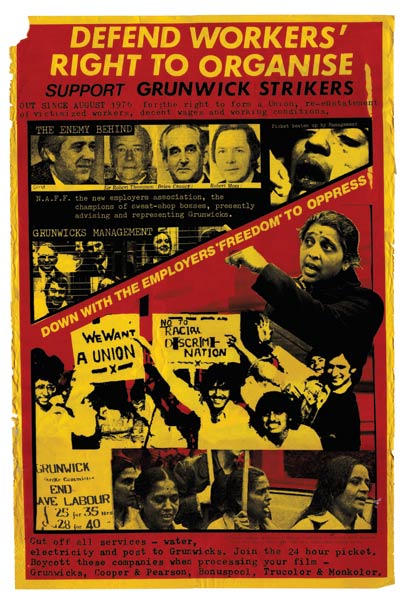

Confidence was high given the recent union victory for equal pay at nearby Trico, a similar type of workplace to Grunwick. However, the Grunwick management was standing firm against the strikers and was receiving the full support of the Tory party, the national press and an organisation called the National Association for Freedom (NAFF), which backed a whole series of reactionary causes over the years.

This “secondary picketing” by the capitalists required a similar approach from the unions, and they got it in the form of the postal workers. Members of the postal workers union (then called UPW, later part of the UCW) refused to deliver mail to the Grunwick sites, and in November 1976 refused to sort or allow mail for the site to be handled at all. In a post-based system, this left the Grunwick management facing potential economic ruin within days.

A special debate was called at Westminster at the behest of Tory MPs to demand that the Labour government take action using existing laws to force the postal workers to handle Grunwick mail. Under pressure from a nervous Labour leadership, however, the right-wing national leaders of the UPW put pressure on the local union to suspend the mail blockade in return for Grunwick management agreeing to talks via ACAS. Defeat was grabbed from the jaws of victory.

It soon became clear that Grunwick had no intention of honouring any ACAS negotiated agreement and had indeed awarded a 15% pay increase to any worker at the site who would not join a union. The later ACAS decision to support union recognition was rendered void by its failure to canvas all workers, even though Grunwick management had prevented such a survey from happening. In effect, the bosses could ride roughshod through the law.

Meanwhile, the strike continued into 1977. As spring turned to summer, mass pickets were organised outside the factory to ramp up the pressure and keep the fight alive. One such protest on 22nd June became a national day of action, with thousands of workers turning up at the crack of dawn in Dollis Hill to support the Grunwick strikers. Amongst those present was a large turnout of miners, led by Arthur Scargill. This tremendous act of solidarity would not be forgotten, both by other unions and by the police, when the miners themselves took action in the great strike of 1984-5.

Armed bodies of men

As the exhibition reminds us, the police were not innocent observers in this strike. Clear evidence has emerged of collusion between the police forces and the Grunwick management. The infamous Special Patrol Group (SPG) would be used for the first time in British history to intervene in an industrial dispute. At the mass protests, covert filming was done, and several police agent provocateurs were identified by union activists.

Of course, it went further than this, and the various mass protests were marked by indiscriminate arrests by the police using obscure laws about rights of entry, etc. Over the course of the strike, around 550 people were arrested – an unheard of number for an industrial dispute in Britain. Similarly brutal tactics were later seen with the police attacks on the miners in 1984-85 and the Wapping print workers. The Grunwick arrests were marked by the usual barrage of press reports about mob-violence, etc., and the Tories were not slow to join in.

As usual, the Labour and trade union leaders, who only wanted to have a quiet life, quickly became scared and, hostile to any signs of union militancy, begun to look for a way out. The Labour government gave it to them in the form of an official inquiry led by the ever-faithful Lord Scarman. The inquiry was used to try and wind the dispute down. APEX called off the pickets pending the outcome, allowing the initiative to be lost.

The strikers knew, however, that no learned judgement from Lord Scarman (or whoever was pushed forward) would bend the will of the Grunwick management, particularly over the issue of union recognition. The bosses knew that their grip over a compliant workforce could not be maintained should there be a union presence. Scarman would in time kindly recommend the re-employment of the strikers and the recognition of the union, but the Grunwick bosses simply ignored the judgement. For good measure, the House of Lords, acting in the class interests of the bosses, as always, made clear that the management did not have to recognise the union.

A question of leadership

The union leaderships, afraid of what might happen, soon abandoned the strikers, who bravely carried on with rank-and-file support until defeat was finally admitted in July 1978. For good measure, a number of the strike leaders were chucked out of APEX for protesting at the TUC’s lack of action – nothing changes it seems.

Grunwick remained a non-union hellhole until, with trade falling, it went under and closed in 2011. One of its most high-profile owners, George Ward, became a leading light of the local Tory Party until he was thrown out for trying to fiddle internal elections. Blaming Thatcher for not backing him, he died a bitter man in 2012.

The strike leader Jayaben Desai remained a prominent figure in the support of other struggles of Asian and black workers in the workplace over the next few decades. She died in 2010 having received a number of national awards from trade union bodies in recognition of what she started.

The Grunwick strikers, standing daily on the picket lines and facing attacks from police and the Tory press, had become politicised in the space of a few short months and would not soon forget what they had learnt. This would in turn be passed on to other workers, particularly those based in the least-well organised and most downtrodden sections of working life. It is possible to see how these lessons have been taken up over the years, right up to the current struggles of the Deliveroo workers.

Unite and fight

The capitulation of the trade union leaders did not save them from the attacks of future governments, starting with Thatcher after 1979. The Tory anti-trade union laws were based directly on what had been learnt from the Grunwick struggle. Had the union leaders used the force available to them in the form of millions of workers under their banner, they could have sent the Grunwick bosses running and laid down a marker to the Tories of what they might expect should they launch any attacks on workers or union rights.

The capitulation of the trade union leaders did not save them from the attacks of future governments, starting with Thatcher after 1979. The Tory anti-trade union laws were based directly on what had been learnt from the Grunwick struggle. Had the union leaders used the force available to them in the form of millions of workers under their banner, they could have sent the Grunwick bosses running and laid down a marker to the Tories of what they might expect should they launch any attacks on workers or union rights.

The miners and the print workers, to give the most high-profile examples from the decade that followed the Grunwick strike, later took on the bosses and the Tories also; but again they did not get the required support from the leadership of the labour movement, despite heroic displays of solidarity from the rank and file.

Forty years on, we should salute the struggle of the Grunwick strikers. That it was a strike of Asian workers – a section which up to then had largely been absent from the leadership of high-profile industrial struggles – demonstrated what was possible, despite decades of divide-and-rule tactics being used on the industrial shop floor. The solidarity of rank-and-file workers was an inspiration, striking fear both inside the boardrooms of big business and in the cosy offices of more than a few union bureaucrats.

The stand of the Grunwick strikers must inspire a new generation of trade unionists, black and white, to fight against the attacks of the bosses and the rotten capitalist system that is to blame. This is the best way to honour the Grunwick strikers and the militant example that they have provided.