In the past five years a fundamental transformation has taken place in British politics. The capitalist economic base of society has become exhausted. In its turn, the old British political establishment finds itself out of step with the new economic reality. This is stirring up powerful forces deep in the bowels of society.

In the past five years a fundamental transformation has taken place in British politics. The capitalist economic base of society has become exhausted. It no longer develops society, but rather drags it down like a leaden weight. In its turn, the old British political establishment finds itself out of step with the new economic reality. All that is real becomes unreal. This is stirring up powerful forces deep in the bowels of society.

Britain, like the rest of the advanced capitalist world, is an overwhelmingly working class society. The long-term decline of British capitalism – with a simultaneous trend of national income increasingly going to capital at the expense of labour – squeezes of their privileges occupations such as teachers, bank workers and civil servants, previously honoured and looked up to with reverent awe.

It is also an increasingly polarised society. By 2016, Oxfam predicts 50% of all wealth will be concentrated in the hands of the richest 1%. There is a proliferation of “zero-hour contracts”. Five million earn less than the minimum wage. Over 1 million Britons rely on three days’ emergency food given by food banks, the majority of which are not homeless but “working poor”.

These developments in society have accelerated and become exacerbated since the introduction of austerity, leading to despair, anger and frustration building up deep within society. In light of this, many woke on the morning of May 8th to a certain degree of shock, finding that the Tories had been voted into government for another five years.

Capitalist democracy

Another five years of Tory government does not indicate satisfaction with the situation in Britain – far from it. Only 24% of the electorate voted Tory. A total of 37% voted for the right, if we add the UKIP and LibDem vote. And the UKIP votes must be treated with caution, as a vote for UKIP was seen by many not as one for the establishment, but as a kick against it. According to the Ashcroft poll, half-a-million UKIP votes were ex-Labour.

Another five years of Tory government does not indicate satisfaction with the situation in Britain – far from it. Only 24% of the electorate voted Tory. A total of 37% voted for the right, if we add the UKIP and LibDem vote. And the UKIP votes must be treated with caution, as a vote for UKIP was seen by many not as one for the establishment, but as a kick against it. According to the Ashcroft poll, half-a-million UKIP votes were ex-Labour.

Britain is now governed by a party that, even considering the limited nature of democracy under capitalism, has little democratic mandate. The five million votes that went to UKIP and the Greens are represented by two MPs. The Liberal Democrats, who recorded half that number, were rewarded with four times the seats. The Scottish National Party, who had a million votes less than the Liberal Democrats, now have 56 MPs!

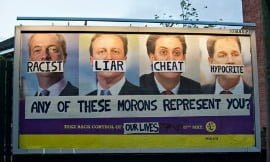

All this shows the extremely limited nature of democracy under capitalism, where, as Marx said, you get to vote once in every three to six years which member of the ruling class is to misrepresent you. The capitalist state, including Parliament, is meant to work for the capitalists. But it is lending less credibility to their rule than ever before. They are finding it increasingly difficult to work in their favour.

Liberals

The Liberal Democrats are now a spent force. This is a blow to the establishment. The liberals played a useful role as a shock absorber in the parliamentary system, soaking up disaffected Tory voters who might have otherwise voted Labour.

If the Liberal Democrats had a soul, they sold it for thirty pieces of silver in 2010. The price was the betrayal of their base of support, including huge numbers of young people who voted for Nick Clegg’s party as a way to abolish tuition fees, and who were subsequently forced to mobilise en masse at the end of that same year, as the Lib Dems not only reneged on their policy, but joined with the Tories to raise them to £9,000.

Five years later, what was the result? 85% of the Liberal parliamentary fraction has now been wiped out. The Lib Dem betrayal claimed the scalps of coalition ministers Vince Cable and Danny Alexander, as well as former party leader Charles Kennedy, and deputy leader Simon Hughes. Nick Clegg was only propped up through Tory tactical support in Sheffield Hallam, a farewell gift from David Cameron for services rendered.

Such a collapse in support was long predicted by many following the betrayal of much of their base in the last parliament. That is has come to pass underlines the extreme instability in the system.

The long term decline in British capitalism has been marked for a whole historical period with the decline of liberalism. The Liberals were out of power for so long that their policies began to take on a semblance of un-reality, from the point of view of the needs of British capitalism. Some even believed they had become a party of the left. All such illusions were shattered as they were brought into government, quickly conforming to their tradition as a party of the rich.

The Labour Party

Labour has also paid the price for its past actions, more indirectly, but more significantly. This is a result of the class nature of the Labour Party, which the working class have historically seen as their party.

As her majesty’s loyal opposition, Labour voted with the Tories for austerity, including as recently as this January, when they supported the Con-Dem coalition’s “budget responsibility charter”, which included plans to slash a further £30bn from public spending. Only five Labour MPs rebelled.

Scandalously, in 2013, Labour abstained on the notorious “workfare” bill, preventing 250,000 job-seekers to receive £130m in compensation for being put into what was effectively forced labour by the Tory government. Forty-four MPs rebelled, yet Labour’s abstention allowed the bill to pass.

At a local level, Labour has passed through huge cuts to public services without offering any fight. Any Labour councillors unwilling to toe the line have been subject to disciplinary measures, such as the recently expelled Hull councillors Gill Kennett and Dean Kirk.

This shows how out of touch the Labour leadership has become. It demonstrates, as Trotsky said, the “betrayal inherent in reformism”, which only naively aspires to amend capitalism, to make it “more human”, and cannot contemplate breaking with it.

This naivety becomes dangerous utopianism when placed at the head of the workers’ movement. In the present period, when there is nothing to be gained from an economic system in decline, the choice is to break with reformism or to capitulate completely to big business and become the faithful servants of the ruling class. As can be seen from the recent example of PASOK in Greece or Francois Hollande’s Socialist Party in France, the social democratic leaders have become reformists without reforms. Instead, in this epoch of capitalist crisis, they can offer only counter-reforms – the same cuts and austerity as the bourgeois parties.

Scotland

The utter weakness of reformism has been most starkly revealed in Scotland. The revolutionary implications of what has occurred north of the border is a book sealed with seven seals to the Labour leadership. They dismiss the movement of the Scottish people as crude nationalism. Through their participation in the “Better Together” campaign, a unionist alliance with the Tory-Lib Dem coalition of austerity, they have ironically brought closer the break-up of the United Kingdom they sought to defend.

The utter weakness of reformism has been most starkly revealed in Scotland. The revolutionary implications of what has occurred north of the border is a book sealed with seven seals to the Labour leadership. They dismiss the movement of the Scottish people as crude nationalism. Through their participation in the “Better Together” campaign, a unionist alliance with the Tory-Lib Dem coalition of austerity, they have ironically brought closer the break-up of the United Kingdom they sought to defend.

It is significant that David Cameron shied away from visiting Scotland in order to defend the “No” vote. He understood this would be too much to swallow for the Scottish people. It is also a tacit recognition of the class nature of the independence movement, which is primarily motivated by a desire to separate the Scottish people from austerity, Westminster and Tory governance. Instead, prominent Labour party leaders did Cameron’s bidding, de facto acting as spokespersons for British capitalism.

The Labour leadership have bought wholesale big business’ argument for austerity. This is politically reflected in their attitude to the independence referendum, where they formally joined the same campaign as the Tories and Lib Dems. The Labour Party could have supported a “No” vote on a working-class basis, arguing for a bold socialist alternative to the Tories. But rather than make the case for unity of the British working class in the fight against the Tories and austerity, they based themselves on British nationalism, behind which was thinly disguised their own programme of “austerity-lite”. But it is the fight against austerity that is the prime mover of the Scottish movement.

The Labour-led victory of the “No” campaign was a Pyrrhric victory. They paid the price with the mass desertion of their traditional base to the SNP. It is a position that will take a generation to recover from, if ever.

General Election

Between the referendum and the General Election the writing was on the wall for the Labour Party in Scotland. But the election results bore this out with devastating clarity. Revulsion and disgust were the general post-referendum sentiments of the Scottish workers to Labour. They did not hold back their feelings come polling day.

Between the referendum and the General Election the writing was on the wall for the Labour Party in Scotland. But the election results bore this out with devastating clarity. Revulsion and disgust were the general post-referendum sentiments of the Scottish workers to Labour. They did not hold back their feelings come polling day.

Cameron, representing the short-termism of the senile British ruling class, attempted to whip up English chauvinism, threatening the perspective of a Labour-SNP alliance that would lead to a second referendum and the break-up of the United Kingdom. This will be to no avail for the British ruling class; such is the resounding result in Scotland that a second referendum is almost inevitable. But Cameron’s manoeuvre served to stampede many Lib Dem and UKIP voters back into the arms of the Tories.

On the other side of the equation, Miliband was under pressure from his MPs in Scotland to rule out a Labour-SNP alliance, offered by the SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon. This they vainly hoped would fling the Scottish workers back into the arms of Labour, through fear of a Tory government. But like a modern-day King Cnut, Miliband proved incapable of turning back the tide. Although it must be said, it is questionable whether any promises would be taken seriously by the Scottish workers given Labour’s role in the referendum.

Rather than rally the Scottish workers on the basis of fighting the Tories on an anti-austerity basis, Miliband framed his proposal to the Scots in the purely negative terms of tactical voting: “No deal with the SNP – so vote Labour to keep the Tories out of Westminster!” But the Scottish workers, like the British workers, are sick of parliamentary manoeuvres and voting for the “lesser evil”. They took one look at Milliband’s proposal and asked “What’s the difference?” Unsurprisingly, Labour are now referred to as “Red Tories” by many north of the border.

The Labour Party did not add one vote to their cause by refusing an alliance with the SNP. By accepting that there is no alternative to capitalism, the Labour leaders have become another voice for austerity. And by capitulating to Cameron’s argument about the SNP and the break-up of the United Kingdom, they have become the servants of crude British nationalism.

The ghost of betrayal paid back the Labour party in kind. In the General Election in Scotland the Labour party was “unseamed from the nave to the chops”, losing 40 of its 41 seats, including the leader of the Scottish Labour Party, Jim Murphy, who has since resigned. The Labour Party’s electoral campaign coordinator and shadow foreign secretary, Douglas Alexander, lost his seat to Mhairi Black, who as a 20-year old student, is the youngest MP in Westminster since 1695.

It is the worst Labour Party result in Scotland ever. You have to go back to before the 1906 elections, before the Labour Party was properly constituted, to find the Labour Party with not a single seat in Scotland. But the loss for the Labour Party is not just electoral, but has hit them hard in terms of support from the most active layer of the working class. For example, the trade union caucus of the SNP now has more members than the entire Scottish Labour Party.

The actions of the Labour Party leaders are of course not new. And the revulsion it inspires is by no means an exclusively Scottish response. It has existed for many years, if not decades. The difference in Scotland is that this burning sense of frustration and radicalisation was given a vehicle in the form of the anti-austerity, anti-westminster left nationalism of the SNP. South of the border no such vehicle existed, although the five million Green and UKIP votes was symptomatic of a similar anti-establishment mood.

The crisis of reformism

Capitalism equalizes everyone down to the same level. It is the basis for a socialist consciousness. The social nature of production under capitalism reinforces this, as does the class struggle itself. The workers may hate the class enemy, but also accept their unambiguous class nature. A worker may even be heard to remark “at least you know what you’re getting with the Tories.” Such a response, rather than being a sign of backwardness, is completely understandable given the messages emanating from the current Labour leadership, which inspire no confidence.

What invokes a different type of hatred, however, is betrayal. The bitter experience of misplaced confidence, a betrayal of solidarity and comradeship, provoke the contempt of the workers, who can only rely on each other in the class struggle. And the struggle to change society is one enormous social act, which cannot tolerate careerism, betrayal and deceit. The workers disdain for a scab can more than outweigh the open class enemy, which at least they can see clearly.

In May 1968 in France, the Communist Party, in a revolutionary situation, betrayed the working class and handed power back to De Gaulle and French capitalism. The sense of bitter betrayal experienced by the workers marked the terminal decline of the CP, which ever since has been eclipsed by the Socialist Party, whose fortunes received a reverse. Scotland in 2015 is not the same as France 1968, but there is an analogy to be drawn. Those parties and leaders, who at the crucial moment fail to represent the needs and demands of the workers, will pay a heavy price.

One of the defining characteristics of the present period is the exposure of all the half measures that cannot address the root cause of capitalist crisis. It is part of the polarisation taking place in society. The Liberals have fallen on their swords in defence of the capitalism system. As a capitalist party they could not do otherwise.

The events in Scotland are part of the same process of economic and political instability in society. There is no longer any middle ground on which to rest; no stable ground for the ideas of reformism. The leaders of the labour movement must either offer and fight for a bold socialist alternative; or they will be forced to carry out the cuts that capitalism requires. The fate of Scottish Labour is as a massive warning sign for the rest of the movement.