“We didn’t think we were that strong.” Sheila Douglass

It was not the first such strike, and it would certainly not be the last. However, by standing up against bosses, union officials, and even other workers, they would send a message that has stood the test of time and inspires still.

On 7 June 1968, 187 female sewing machinists at the Ford car plant in Dagenham went on strike over the cutting of their pay. The pay cut was thanks to a dubious reclassification of the firm’s wage structure.

Dagenham was one of the largest and most profitable car-production plants in Britain. The factory dominated the whole area, covering 475 acres and employing 40,000 workers at its peak, operating production on a 24-hour shift system.

The action of the women – led by Rose Boland, Eileen Pullen, Vera Sime, Gwen Davis and Sheila Douglass – acted as a catalyst for the 1970 Equal Pay Act, which made discrimination against women by paying them less for equally skilled work illegal. They were supported by the women at the Ford Halewood plant in Merseyside, who also walked out on strike.

The signing of the Equal Pay Act in 1970 was a huge victory for working women. During the second reading of the Act, Shirley Summerskill MP stated that the strikers had played a “very significant part in the history of the struggle for equal pay”.

The women from Ford Dagenham and Halewood stood up against the bosses, against the press, against the government and, at times, against their male co-workers and trade unionists. They were brave and principled women who fought for workers’ rights and their fight should be celebrated and studied 50 years on, at a time when the gender pay gap is still being fought against in Britain and elsewhere.

Their struggle inspired generations of women workers to stand up and take industrial action during the years that followed.

Year of revolution

1968 was an explosive year for workers fighting against oppression and exploitation – not least in France, where the events of May ‘68 had shaken the establishment to its core with the trade unions and student movement coming close to taking power.

1968 was an explosive year for workers fighting against oppression and exploitation – not least in France, where the events of May ‘68 had shaken the establishment to its core with the trade unions and student movement coming close to taking power.

This was at a time when Britain had a significant manufacturing base. It was a time of mass production and the assembly line.

In 1931, Ford set up its plant in Dagenham on the borders of Essex and East London, which was to become the centre of its manufacturing, sales and servicing for the whole of Europe. By 1950, over a million cars were rolling off the Dagenham assembly lines each year. This number increased to 1,400,000 by 1955.

With the speed-ups came unofficial strikes. Pay was considered good for the area, but the company worked you into the ground. The Dagenham plant was renowned for squeezing all they could out of the workers. “No one makes old bones at Ford,” was a popular saying, referring to the short life span of many workers, worn down by the intensity of labour. One worker would later refer to the production line as a “living death.”

“They wouldn’t stop that fucking line,” said one worker. “You could be dying and they wouldn’t stop it.”

The working conditions in the plant were disgusting, with the women being made to work in an “old shack with an asbestos roof” that let in the rain and housed rats and mice.

“In summer it was like a sweat house and they came round and gave us lime juice and salt tablets,” said Vera Sime, one of the striking machinists. In winter, the women stuffed the holes in the ceiling, blocking out cold winds and rain to keep warm. Furthermore, they worked with machines that were without safety guards, which meant injuries were very common.

Despite all the problems, the women enjoyed the class camaraderie of the factory despite it being unsafe and unclean. One worker known as ‘Effing Eileen’, who loved to swear, was seen wearing a hat that said ‘bollocks’ on the front during Henry Ford’s visit to the Dagenham factory. The humour of the workers could not be suppressed despite the best efforts of management.

Militant traditions

The Dagenham women’s fight was primarily centred around how they were treated as workers. Their fight did not begin as a civil rights protest about gender equality. The women who went on strike were not second-wave feminists burning their bras in protest against gendered standards. The strike began with the simple request that their work be recognised as skilled in the same way that the work of others, who happened to be men, was so recognised.

The Dagenham plant already had a tradition of militancy, which would continue in the following decades with a series of walk-outs, including a three-month strike in 1971. Up until 1968, that militancy had primarily involved just the male workforce. Now things would change.

The immediate cause of the strike in June 1968 was due to a grading restructure that moved the women workers down from Grade C, skilled workers, to Grade B, unskilled workers. They argued that their sewing skills — making seats for Zephyrs and Cortinas — should put them on the same pay level as the spray-painters who, under the new pay structure, were earning 15% more than the women. Even within each wage category, women earned less than men.

“The discrimination against the machinists was symptomatic of the company’s more general discrimination against women,” explained the August 1968 Report of the Court of Inquiry under Sir Jack Scamp.

“Of 38,000 male production workers, 9,000 were on Grade C – roughly one in four. The 850 female production workers included only two in Grade C – one in 400. Even with technical and clerical work included there were only 12 women in C. There were no women at all in the two top grades D and E.”

Understandably, the machinists were angry that they were to be now considered unskilled, despite the fact that they had to pass tests in order to gain employment with Ford. The new pay structure left the machinists’ pay as the same as that of the cleaners, whose work required less skill.

And so, with encouragement from some in the union, they began their strike against Ford’s action.

Not a wheel turns…

The restructuring of their pay meant the women were now forced to act – forced to fight for fair wages, in a job that they didn’t mind so much as put up with – so that they could continue to feed their families and pay the bills.

The strike came when it did, not because the women had finally had enough of the working conditions, but because the wage cuts profoundly affected their ability to get by.

The strike went far beyond just inconveniencing the management of their own department. The women sewed the seats for the cars. And so, not long after they put down their tools, 9,000 male workers who assembled the cars at the Dagenham plant were laid off as a consequence, as there were no seats left to go into the cars. The whole factory ground to a halt. Machinists at the Halewood plant also were now out over the same issue, threatening the whole of Ford’s UK operation.

Bill Batty, Ford’s UK Managing Director, threatened the loss of 40,000 jobs if the strike continued. And the financial effect that the dispute had on the company did not go unrecognised. The walkout was estimated to have lost the company export orders worth £117m in today’s money.

This really raises the question of who it is that controls society. That 187 women could cause such disruption and loss of earnings for such a large company reveals the power that workers have.

Rather than it being the bosses who create wealth in society, the Dagenham strike proved yet again that it is the workers that create value and the bosses who cream off a huge slice of profit from the top. Without workers and their labour-power, capitalists would have nothing.

The strike went politically further than the workers could have imagined to begin with too. Their initial aim of having their work recognised for its equal value with that of the men in their own factory was broadened out to become a fight for equal pay for all women workers.

The placards and signs that the workers used on their picket lines were testament to this, bearing slogans such as ‘Equal rights in pay and grading’; ‘end sex discrimination’; and the infamous unfurling ‘disaster’ of the ‘we want sex equality’ banner, which caused a sensation when the last word took far longer than the rest of the banner to be displayed, causing shouts of ‘I know what you mean!’ from passing motorists!

What can be seen through the slogans used throughout the strike is the shift from the initial demand for recognition of their labour as skilled, to the demand for equality with male workers in terms of pay; equality in how the women’s’ labour was graded; and the call for equal pay.

Uphill struggle

But their fight wasn’t easy. Some of the strikers were opposed by men who had been laid off, arguing that the women should go back to work so that they could too. Some were opposed by the wives of these men, who were now struggling financially and therefore putting pressure on the strikers.

But their fight wasn’t easy. Some of the strikers were opposed by men who had been laid off, arguing that the women should go back to work so that they could too. Some were opposed by the wives of these men, who were now struggling financially and therefore putting pressure on the strikers.

“Some of the men said: ‘Good for you girl’ but others said: ‘Get back to work, you’re only doing it for pin money’,” said Eileen Pullen. “A lot of women jeered us. They didn’t go to work and their husbands were at Fords and we’d put them out of work”.

“But our wages weren’t for pin money,” added Gwen Davis. “They were to help with the cost of living, to pay your mortgage and help pay all your bills. It wasn’t pocket money. No woman would go out to work just for pocket money, would she? Not if she’s got a family.”

Davis gets to the heart of the strike in this comment. The strike was about providing for families and being able to live off the wages the company paid them. Working class families couldn’t afford to live off just one wage in many cases, and not all women had a partner to support them and their family financially.

In reducing their pay, the Ford bosses were simply increasing their exploitation of the machinists in order to increase their profits.

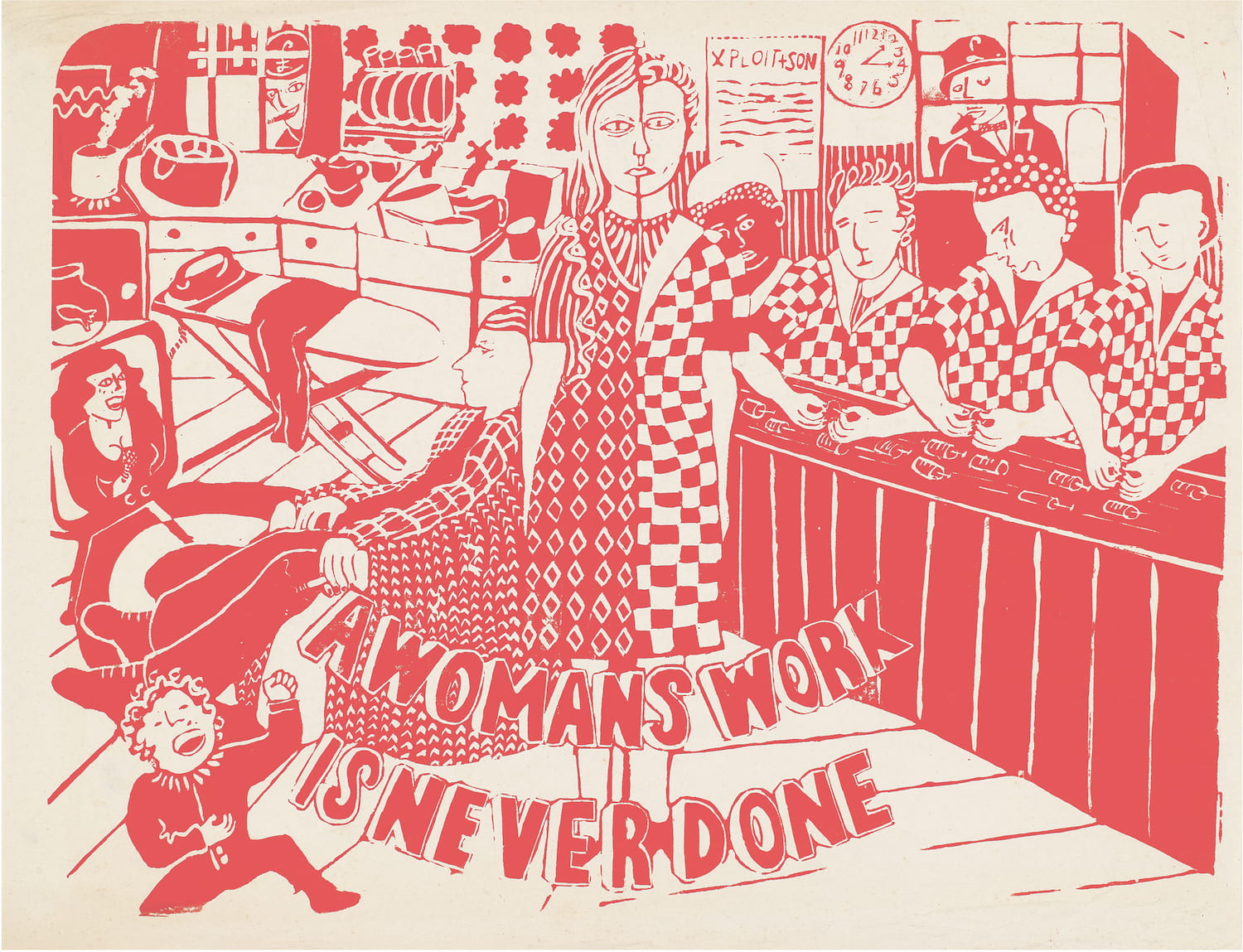

This was what the strike was about – and this is what oppression of women more generally is about. If women are oppressed and seen as less able and less worthwhile than men, they can be exploited along the lines of pay and conditions, on top of their unpaid labour in the home, and business owners directly profit from that.

“Two things were happening to the assembly-line worker”, explains Huw Beynon. “He saw himself being paid a rate just above that paid for sweeping up, and he was being laid off. He didn’t understand why the new payment system was discriminating against him. He didn’t like it and he liked being laid off less. The strikes by women increased the frustration of these workers. It was like a whip to their backs. Here they were they being laid off because the women were ‘having a go’. Why for Christ sake didn’t they have a go as well? At least that would be something positive, if only blindly defiant. ‘The women’, they claimed, ‘are the only men in this plant.’” (Working for Ford, p.176)

Added pressure on the women strikers came from some trade union officials – the very people who should have supported the female trade unionists.

The women of Dagenham said that union leaders did not think much about losing a mere 187 women’s union dues out of thousands of workers at the plant. Bernie Passingham recalled how they faced opposition from some within the TGWU (Transport and General Workers’ Union, now UNITE):

“Some of our national officials weren’t all that agreed with what we were doing. They didn’t think it was right.”

A female shop steward at the time, Lil O’Callaghan, had to push the TGWU site convenor Bernie Passingham, who was meant to be representing the women, into supporting the cause, barking at him to: “get off your arse Bernie and do something about it.”

Fighting for fair pay

With the Ford Dagenham plant at a standstill, the dispute was now of national significance. And, given the rise in trade union militancy (including a sharp increase in unofficial strikes) and the decline in the economy, Barbara Castle, secretary of state for trade and industry, intervened to insist on a deal.

With the Ford Dagenham plant at a standstill, the dispute was now of national significance. And, given the rise in trade union militancy (including a sharp increase in unofficial strikes) and the decline in the economy, Barbara Castle, secretary of state for trade and industry, intervened to insist on a deal.

This was mainly due to the enormous economic pressure that the strike was having on the British economy, with “concerns” already being raised by big business and the bankers about the state of affairs.

Following this move, the strike came to an end, three weeks after it began. It resulted in an immediate increase in the machinists rate of pay to 8% below that of men, rising to the full Grade B rate the following year, but not raising them to Grade C status.

The union were satisfied with this abolition of the women’s rate within category B and felt that the re-grading was too much to ask from the company. This offer was put to the machinists. Although not unanimous, they voted to return to work, but still at the unskilled rate.

Speaking about her experience, one of the machinists said:

“I was really annoyed that what we came out for originally was swept under the carpet. I suppose you could say that we started off equal pay but it wasn’t equal pay really.”

This clearly shows that the fight for ‘equal pay’ isn’t enough to achieve gender equality. In this fight, the B grade women’s rate was abolished; equal pay at the B grade was achieved. But does that mean equality? Of course not, when women’s work was still seen as less skilled than men’s.

Clearly the issue is about equal rights for equal work. And this historic strike, although it began the conversation about equal pay, did not achieve equality.

One clear consequence of the strike (and those which followed) was the passing of the Equal Pay Act 1970, which came into force in 1975. This aimed to prohibit inequality of treatment between men and women in terms of pay and conditions of employment for the same work.

Naturally, the bosses complained like hell about the “costs” of this reform and would try every means to get round it, something that has continued ever since. As such, we should be clear: this reform was won by the organised workers, not by the “fairness” of the employers.

However, for the machinists in Dagenham, parity in pay and grading was not finally achieved until after a further six week strike in 1984 – sadly, just in time for many of the original strikers to retire.

The Dagenham strike was far from being a “feminist” strike led by women wanting to defeat the patriarchy or questioning the unfairness of women being paid less than men. Rather, it was led by working class women fighting against poverty wages and against the injustice that their work be seen as less skilled than the work of the paint sprayers – regardless of gender. This was a fight over working conditions and fair pay, not gender equality.

The struggle continues

Although the Equality Act of 2010 enshrined gender pay equality in law, the pay gap – though narrowed – persists. Currently standing at around 19 per cent, it means women workers still earn, on average, only 81p for every £1 a man earns.

Although the Equality Act of 2010 enshrined gender pay equality in law, the pay gap – though narrowed – persists. Currently standing at around 19 per cent, it means women workers still earn, on average, only 81p for every £1 a man earns.

However, in order to close that gap, we need to look at what causes it. Today, compared to when the Dagenham women were striking, the pay gap is not caused by women workers being paid less to do a similar job (although that does still happen at times).

Now, it is caused by the fact that women workers are still discriminated against for becoming mothers and taking time out of work; for being less flexible with their time for having to raise children; and by having less access to highly paid jobs.

Women workers are paid less because they work in more precarious conditions, under zero-hour contracts, doing (sometimes multiple) part-time jobs, struggling because of their inflexibility.

If we truly want equal pay, we first must have a society that provides equal maternity and paternity leave at full wages; and that provides free childcare for all children, including in the evenings, so that women can attend trade union and political meetings and participate fully in the re-shaping of working class organisations.

We cannot artificially create opportunities for women workers to take in higher paid jobs and political positions. We have to change the material conditions that currently prevent women from doing this.

Simply put, we must do away with capitalism – a system that directly profits from the oppression of women workers – from viewing women’s labour as less valuable and from greater exploitation of women workers. Only then can we win the fight for equal pay and for gender equality.