This article is a part of our new booklet, The Crimes of British Imperialism, which uncovers the bloodstained history of the world’s oldest capitalist power.

The booklet has been produced as part of the Revolutionary Communist Party’s ‘Books not Bombs’ campaign. The first step towards fighting imperialism and militarism today – in Britain and across the globe – is to understand it from a scientific, Marxist perspective.

Order The Crimes of British Imperialism today – on sale at a third off until 31 December!

The great imperialist powers like to cloak their plunder of the world in fuzzy humanitarian notions: democracy, education, assisting self-determination – in some cases even anti-imperialism! The ‘benevolent Brits’ are no exception.

The curriculum, museums and the press all unite to portray the collapse of the Empire – through a wave of independences after the Second World War – as a smooth transition accorded from the good of the Queen’s heart.

Nothing could be farther from the truth.

The Anti-British National Liberation War in Malaya (called “Peninsular Malaysia” today) is perhaps one of the starkest examples of calculated cruelty from the British ruling class in its efforts to defend its profits.

The “emergency”

The episode is known as the “Malayan emergency” because, as some defenders of British imperialism tacitly admit, insurers in London would not have paid out compensation to plantation and mine owners in a civil war – which is what this was.

The conflict officially lasted from 1948 until 1960, although most of the fighting took place until 1958, a year after Malaysia obtained formal independence.

Over 40,000 British and Commonwealth troops were mobilised against a peak of 7,000-8,000 guerrillas from the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the armed wing of the Malayan Communist Party. The vast majority of the latter were eliminated, with 6,781 killed and 1,287 captured.

For this reason it is commonly described as the “one of the only successful counter-insurgency operations by the West in the Cold War”.

US imperialism would later – unsuccessfully but to far more devastating effect – apply the British military lessons of fighting guerrilla warfare in the jungle during the Vietnam War.

This was especially a testing ground for the mass use of ‘Agent Orange’, Napalm, and forced relocations.

But the British tactics are also praised in the establishment narrative for the use of a “hearts and minds approach”. This is a nicer way of saying that the British administration used divide-and-rule tactics to isolate the communists politically.

Of course, crumbs were put on the table as part of this “hearts and minds” process, such as food aid delivered by aeroplane, wage rises, democratic rights extended to the Chinese minority, formal independence and “extending education”.

These measures are frequently latched on to as if to say “well, the British did some bad things to win the war, but they did loads of good things for the local population as well!”

In reality, we need to view these small concessions against the backdrop of devastating economic and social conditions created by British imperialism, as well as their political backstabbing and most importantly the scale of the terror inflicted during the war.

Why were the British in Malaya?

British capitalism first came to Malaya under the banner of the East India Company, and wrested control of its main targets Singapore, Penang and Malacca from the Dutch through the intermediary of the Napoleonic Wars.

In these early stages Britain was only interested in trading outposts and, significantly, control over the strategically positioned Straits of Malacca.

Up until the 1860s – when pre-monopoly capitalism was still in bloom – the major powers were still opposed to occupying vast swathes of territory, so much so that in 1852 Tory imperialist Benjamin Disraeli stated “the colonies are millstones around our necks”.

This changed, however, in the last decades of the 19th century.

Britain had previously enjoyed a monopoly position by virtue of being the industrial “workshop of the world”. Now France, Germany and the US were beginning to catch up and contest its might on the international stage.

In the home market, capitalism was transitioning from free competition into monopoly.

Although cartels remained the exception rather than the rule, London-based joint-stock companies and banks began to export capital around the world in search of sources of raw material and cheaper workers to exploit, rather than reinvesting in manufacturing at home.

British capital exported abroad quadrupled in the decade of 1862-1872, then again in the three decades of 1872-1902.

Malaya was a ripe field for such investments, with the abundance of tin and prime conditions for the production of rubber. To this day, Malaysia is responsible for 60 percent of the world’s market share of rubber, although the plant was originally imported there from Brazil by the British.

With such lucrative investments, the British monopolists naturally wanted to see these protected – especially against the grubby hands of their European rivals. The pressure grew on the empire, and in 1874 it was finally forced to intervene.

The governor of the Straits Settlements manoeuvred to get the British candidate Abdullah II elected for Sultan by the chiefs of the Perak region. He in turn became subservient to the British ‘Resident’ in return for their ‘protection’ against foreign aggression.

But just to make sure the Malay aristocracy understood the exact relationship between themselves and the Resident, the British went to war against the Perak chiefs after their rebellion a year later in 1875 and exiled Abdullah.

The ‘Resident’ system was subsequently extended to the rest of Malaya from 1875 to 1895.

These methods were practically carbon-copied from the French installation of a protectorate in Cambodia in the 1860s – which in turn was motivated by their desire to prevent further British expansion from Siam (Thailand).

But crucially, ruling through the old Malay aristocracy granted Britain a relatively stable political situation through which its capitalists could continue to make their profits in peace.

And like the French in Cambodia, they thought it best not to interfere with the ethnic Malays whatsoever – better to recruit the mine and plantation workers from elsewhere in the Empire, and keep all oppressed divided along ethnic lines.

Divide and rule

British imperialism had burnt their fingers in the Perak Wars in 1874, where the heavy-handed methods of the Resident in dealing with local customs and the property rights of the aristocracy met with the resistance of the latter, to the point of the Resident’s assassination.

Moreover, the British could learn from neighbouring Indonesia. The Dutch there subjugated 70 percent of the local Javanese population to forced labour, which led to devastating famines and consequently constant peasant revolts.

Chinese merchants had already begun to make incursions into the tin trade. They were used to import over 500,000 workers from South China by the end of the 19th century, mainly for the tin mines, mills and docks.

At the same time, Western banks and joint-stock companies backed by the sterling and the gold standard eclipsed the pre-existing Chinese capitalists, who became intermediaries between the Chinese workers and their British overlords.

Over 100,000 Indian workers were also imported, mainly in rubber plantations and public works. Today these two ethnic groups comprise 20 percent and 6 percent of the Malaysian population respectively – excluding Singapore, where ethnic Chinese make up three quarters of the population.

The perk for the British was that in addition to dividing Malaya along ethnic lines, these ethnicities were themselves divided: the Chinese by dialect, the Indian by caste, religion and language.

The Malay bumiputra (“sons of the soil”, peasants) were prevented by the British from entering capitalist relations – either by enriching themselves or becoming wage-labourers – through the strict monopoly on the rubber plant.

But simultaneously the bumiputra’s traditional oppression increased.

As Paul M. Lubeck clearly explains: “the organisational and technical superiority of the colonial state actually strengthened the aristocracy’s capacity to exploit their subjects through taxation, licences, corruption and, above all, indirect control over land title transactions”.

The Malay aristocracy, meanwhile, was given the monopoly on administrative and state positions to curtail the power of any Chinese capitalists.

The combination of all these factors pitted the peasant against the worker, the Malay against the Chinese, while keeping both enslaved to British imperialism via the intermediary of the aristocrat or the comprador.

There were no limits to how far British imperialism would go to balance one of these groups against another, always as a means of securing their control.

The Malayan aristocracy had formal power and the best positions in the state until the Second World War, and this had the paradoxical effect of rallying the oppressed, ethnic Malay bumiputra to them due to this apparent privilege over other ethnicities.

After the World War they stripped the aristocracy of a number of these privileges, and granted hundreds of thousands of Chinese and Indians citizenship of the Malayan Union – mainly as a necessary concession to the communists, but partly also to punish the aristocracy for their collaboration with the Japanese during the war.

In 1948 these rights were completely reversed to form the Federation of Malaya, and privileges given back to the aristocracy to form a rallying point for an offensive against the communists.

But the right to vote was quickly given again to the Chinese in 1952 – again to curb support for the communists.

The Empire in crisis

British imperialism, however, was in relative decline, starting with the industrial catch-up of other major powers. And when the world is already carved up, the only means of getting a bigger slice of the pie is to fight for it.

The first major shock to Britain came with the entry of Japan in the World War. It took two months from Japanese troops setting foot in Malaya to the British surrender in Singapore – a defeat which arch-imperialist Churchill called “the worst disaster in British history”. The monolith that appeared to the 1940s peasant to have ruled since the dawn of time collapsed like a house of cards.

At the same time, while the British ruling class kept one eye on the Japanese enemy in front of them, they directed the other to the enemy on ‘their side’: the United States of America.

The US were making their own bid for world domination, and under the guise of the “right of nations of self-determination” were hoping to take advantage of the collapse of their British ‘ally’.

Britain had no military ability to defend its Asian colonies from Japan without the help of the US, and so had no choice if it wanted to cling on to them but to arm yet another untrustworthy ally: the Malaysian Communist Party (MCP).

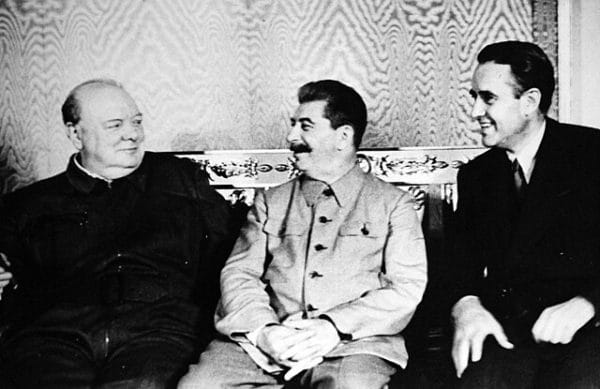

Ironically, this ally would turn out to be more reliable than US imperialism due to the treacherous leadership of Stalin.

Stalin dictated the ‘line’ to Communist Parties across the world – which, in this case, corresponded to his utopian desire for “peaceful coexistence” of the Soviet Union with the imperialists.

We shall return to the role of the MCP. Of note here is the hypocrisy and treachery of British imperialism.

The British imperialists decried the actions of the so-called ‘communist terrorists’ in the 1950s, but in their hour of need they trained the MCP in the same guerrilla tactics to use against their Japanese rival.

The same weapons were literally turned against them, three years later.

The Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) – as the communist resistance front was called – was effectively in power after its heroic struggle, the rapid collapse of Japan in the War, and the absence of the British ruler.

The Empire could only wrest back control due to Stalin’s treachery. The British gave concessions to the MCP including the aforementioned Malayan Union and rewards for guerrillas who handed in their weapons.

The latter went so far that Chin Peng, leader of the MPAJA and later leader of the MNLA, who would resume the struggle from 1968-1989, was knighted with an OBE!

From crisis to downfall

But now came the crux of the British Empire’s disintegration. Britain was not only losing its colonies, but was economically weakened next to the rising star of the US, and desperately needed to make concessions to the working class at home against the threat of revolution.

It is worth noting in passing that at the start of the Anti-British Liberation War, the Foreign Office in Whitehall was not occupied by Winston Churchill but by right-wing Labour gangster and staunch anti-communist Ernest Bevin.

But his imperialist policy received the quiet support of the rest of the Labour government, who were busy forming the welfare state.

After all, if you are going to manage capitalism, as the Labour government was committed to, you have to accept the laws of capitalism. To fund a larger welfare state within capitalism would require that the profits from the plunder of the world by British imperialism continue.

After India gained independence in 1947, Malaya became the next ‘jewel in the crown’ of the British Empire. Most importantly, it was the most important source for Britain to obtain US dollars, of which it was in dire need.

The US had lent Britain $3.75bn for reconstruction post-war, and Britain was at pains to repay this due to the sterling convertibility crisis – triggered by a condition in the loan that let other countries trade in their sterling pounds for US dollars in the British treasury.

But Malaya was the main source of US imports of rubber, the dollar value of which exceeded all British home exports to the US. Some 98 percent of US tin imports came from Malaya.

Keeping production going was therefore the lynchpin – at least to keep the economy from collapsing.

This motive was – unsurprisingly – incompatible with the newfound authority of the MCP built off the back of the World War, and its demand for independence from the British. That is why the British Empire went to war in Malaya.

‘Innocent British’ vs. ‘Communist Terrorists’

On the backdrop of rising prices and unemployment caused by the dislocation of industry following the war, heroic industrial battles were led by the MCP under the General Labour Union (GLU), whose membership ballooned.

A two-day general strike against the arrest of MPAJA members in January 1946 gave the signal and confidence to workers to go on the offensive. From April 1946-1948, 1.2 million workdays were lost in Malaya and 1.3 million in Singapore.

The British responded by banning the GLU, which consequently rebranded itself as the Pan-Malayan Federation of Trade Unions (they finally dissolved the latter in May 1948, when the “Emergency” had begun).

Strikers were arrested and deported. Under the protection, recommendation, and often assistance of the British, the bosses organised to flog, evict, and even execute strikers. Scabs were mobilised, often using Japanese prisoners of war at the beginning of the strike wave.

In effect, the civil war – which had slowly been brewed by imperialism for the best part of a century – was already a fact two years before the beginning of the “Emergency”.

The only ‘crime’ of the communist “terrorists”, who in the history textbooks are counterposed to the democracy-loving Brits, is that they did not take this civil war lying down but stood up and fought back.

Workers organised to picket, fight and execute scabs. And as Phillip Deery amusingly puts it: “[the communists] threatened the lives of managers and occasionally made good on their threats, prompting managers to evacuate their families to Penang.”

According to one historian Anthony Short, violence was in fact higher in 1947 than the first five months of 1948 leading up to the declaration of the “Emergency”.

So it was not, contrary to many accounts, one single act – i.e., the assassination of three plantation owners in June 1948 – that caused the British to escalate the situation.

Rather, they were waiting for the opportune moment: for the industrial struggle to subside after a stalemate with the bosses. This was a point from which they could isolate the MCP and get rid of them once and for all.

The Red-White-and-Blue Terror

Capitalism lights its own forest fires. Whatever we may say about the tactics of the MCP, they pale in significance with the crimes of British imperialism.

The terror of the ruling class is always greater than that of the oppressed, not just because they dispose of the perfected state machinery to carry it out, but because they are compelled to destroy the very forces formerly created to stay in power.

You would not get this impression from many contemporary sources. The National Army Museum states that “on the whole, the Army’s jungle operations were conducted according to the laws of war. The rare exception to this was the deaths of over 20 civilians at Batang Kali in December 1948.”

But the massacre in question was not an isolated incident that can be attributed to the actions of a few bad apples.

In the early stages of the war, the British routinely beat up, tortured, threatened the families of and killed villagers suspected of being linked to the MNLA.

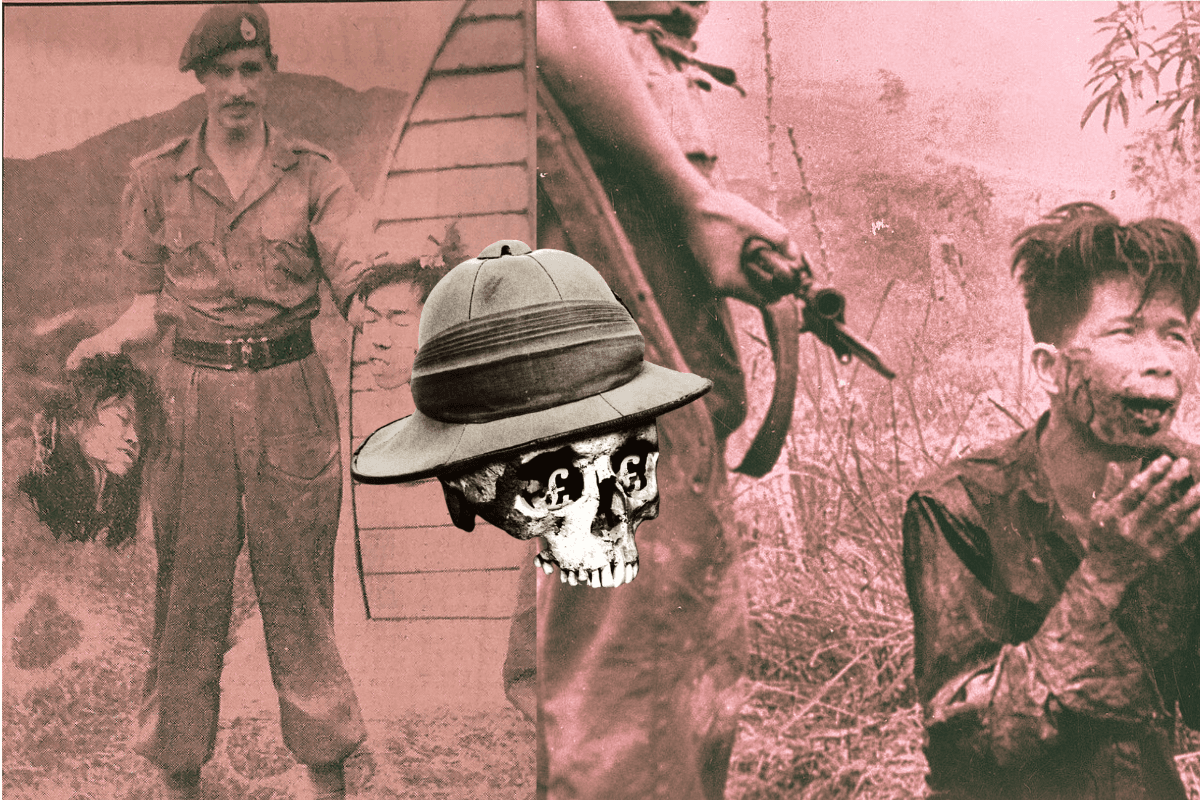

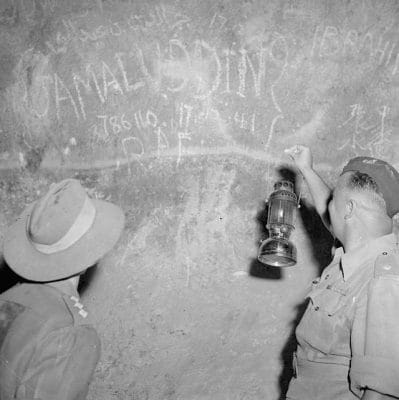

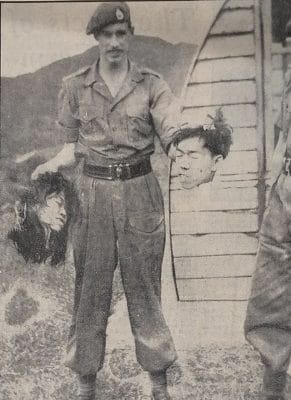

The bodies of killed MNLA fighters were mutilated, and their decapitated heads were exhibited in villages and towns, either to scare the inhabitants or to identify the victims’ relatives by eliciting their grief.

“The deaths of over 20 civilians” is a sickening euphemism for the torture, massacre and mutilation of a village, following which it was burned down by the British – and this was only the high-point in their use of similar tactics.

The MCP had historically found its stronghold within the Chinese workers.

During the 1930s depression and subsequently the world war, due to the bankruptcy and then disuse of the tin mines that employed them, the Chinese workers had migrated in their hundreds of thousands to farm for their survival on the fringes of the jungle.

They were therefore an important source of food and supplies for the MNLA in the early years of the Anti-British War.

To cut off this support, the British changed tactics in the early 1950s.

500,000 of what were deemed “squatters” – 100 percent of the entire population, consisting of 400,000 Chinese, and many Orang Asli (indigenous jungle dwellers) – were forcibly relocated into the euphemistically-called “New Villages”.

They were fenced off by barbed wire, guarded and patrolled, with the population frequently stopped, searched and questioned. Food distribution was strictly organised and centrally overseen, so that no store of rice could be smuggled to the guerrillas.

In other words, 10 percent of the Malay population was interned in concentration camps by the British.

Chemical herbicides were used to destroy the old farms and livestock were slaughtered. Use of the defoliant ‘Agent Orange’ in operations to destroy crops grown in clearings in the jungle led to an official estimate of 10,000 civilians later suffering health problems from the exposure: heart defects, organ malformations and cancer.

The British made liberal use of aerial bombardment, too.

One defence and military correspondent for the British press, Robert Jackson, relates that on one reported guerrilla camp, 545,000lb of bombs were dropped during 1946, 94,000lb at the beginning of May 1947, and 70,000lb on 15 May alone.

He claims that the attack was successful, as “four terrorists were killed!” Netanyahu clearly took some notes for his war on the invisible Hamas.

The British sent 4,500 air strikes in the first five years of the war, which included a forerunner of cluster bombs: the 500lb fragmentation bomb.

There has been no trial for the war criminals who raped Malaya in this period, and no justice for the victims.

The Geneva conventions, it turns out, are only a gentlemen’s agreement between the imperialists and a means to throw dirt at each other when the crimes are perpetrated by ‘the other side’.

When their interests are at stake the “laws of war” only become so valuable as the paper they are written on. And in civil war, they become a farce.

Could Britain be beaten?

Communists stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the heroic fighters of the MCP, whose severely outnumbered forces kept the British Empire busy for over ten years in the fight for national liberation and communism.

But if we did not draw lessons from their own mistakes, we would be forced to draw the conclusion that theirs was a fight that was doomed to fail – as would be the struggle against imperialism today. That would be the biggest lie.

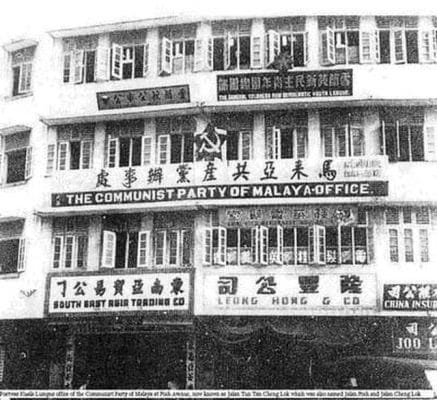

The MCP was born in 1930 out of the branches of the Chinese Communist Party in Malaya.

They began growing among the workers affected by the Great Depression, and between 1935-37 audaciously organised unions and strikes – culminating in the Batu Arang strike of 1937, which saw the declaration of a Soviet (in effect a strike committee) and armed challenge to the British.

Despite its defeat in 1937, the MCP made rapid strides at the end of the decade due to the Japanese invasion of China. It reached 5,000 members – with a much larger base of sympathisers estimated at 100,000.

But despite the MCP’s audacious leadership, which was clearly extremely skilled in agitating and organising, the MCP lacked a theory and programme. In this respect they were ‘yes men’ to the Communist International leadership from the moment of their foundation.

In effect this meant to follow every zig-zag in policy advocated by Stalin who had increasingly turned the International from a tool of worldwide revolution into an instrument of Russian foreign policy.

This led to disaster in the Second World War.

At first, the MCP led a campaign of strikes to halt the British war machine – but when Stalin and Churchill found themselves on the same side in 1941, the leadership made a complete somersault to support the British war effort.

The MCP were right to receive weapons and military training from the British during the Japanese invasion – after all, if the imperialists will give their gravediggers a shovel to whack their enemies with, communists would be daft to refuse it for moral reasons!

The crucial mistake, however, was to sow trust in the British.

The MCP followed Stalin’s line, who thought that by appeasing Britain through derailing revolutions across the world, he could cosy up to Churchill and find an arrangement for “peaceful coexistence” between the Soviet Union and imperialists.

The MPAJA, coming out of the jungle in 1945, held power in their hands. But even after they gave up (some of) their weapons upon the British return, the struggle was not over – as demonstrated in the wave of strikes and violent clashes outlined above, from 1945-1948.

“People’s Front” or class struggle?

The MCP led the industrial struggles in earnest, but the leadership simultaneously pulled wool over their members’ and workers’ eyes.

They focussed their efforts on forming a ‘people’s front’, with whatever element of the Malay middle-class or Chinese capitalists they could find. They wanted to pressure Britain to “grant independence” – something Britain would never do while the communists held the strings.

The classical Stalinist idea was first to achieve independence through an alliance with the ‘progressive’ capitalists. Then, after socialism had been prepared by a lengthy period of capitalist development, in the indefinite future, conduct a struggle for socialism.

The main snag was that – as the strike wave showed – the MCP was the only party that held the force in its hands to challenge British rule.

The capitalists, on the other hand, left the independence coalition precisely as soon as their rule and profits became challenged by the working class in action.

When the strike wave of 1945-48 had receded and the popular front had collapsed, the ranks of the MCP finally began to become disillusioned with the party line. They had not fought a glorious struggle against Japanese imperialism for this!

But they looked with romantic eyes upon this guerrilla war – which in the last analysis had put power in their hands, though mainly through the collapse of the Japanese Empire.

And so instead of building for the next wave of industrial struggle from the underground, they successively isolated themselves from the working class: first by retreating to the jungle, then through giving in to the British tactics to separate them from the Chinese “squatter” communities.

They lost the support of many workers as their sabotage of industry – in the context of a boom and negotiated wage rises – was seen to cause more harm than good.

Finally, after they had framed the war as a struggle for independence divorced from the struggle for communism for almost a decade, the ground was pulled from under the MCP’s feet when the British granted independence in 1957.

After all, their profits were safe in the hands of the Malay aristocracy, who had effectively resumed power.

Long live the Malay revolution!

A communist revolution could have been won in Malaya in the 1940s and 50s. Its defeat was a tragedy for the working-class of Malaysia and the world.

24 hours after the “Emergency” was declared over, the infamous “Internal Security Act” was enacted, which has been used to imprison thousands of activists without trial.

Despite ‘independence’ being declared, the national question was unresolved – riots in 1964 preceded the exit of Singapore from Malaysia, and dozens died in later ethnic riots in 1969.

Meanwhile, 1.2 million people – over twice the amount originally interned – still live in the “New Villages”, 85 percent of them Chinese.

Britain did finally relinquish its dominance over Malaya – only to give it to its now uncontested imperialist rival.

The US used generous trade terms with Malaysia to boost its economy and bolster it as a “bulwark against communism”, as it did in multiple “newly industrialised countries” in Asia.

But the cost of this strategy was to develop the working class at a far faster rate than was otherwise possible, growing it massively. Today only 10 percent work in agriculture compared to 66 percent in the 1960s, and this share comprises the rubber and palm oil industry which are largely dominated by wage-labourers.

Sooner or later the working class will rise again in Malaysia. British managers, beware!