The profound hypocrisy and inherent barbarism of bourgeois

civilization lies unveiled before our eyes, turning from its home, where it

assumes respectable forms, to the colonies, where it goes naked…..The Indians

will not reap the fruits of the new elements of society scattered among them by

the British bourgeoisie, till in Great Britain itself the now ruling classes

shall have been supplanted by the industrial proletariat, or till the Hindus

themselves shall have grown strong enough to throw off the English yoke

altogether. Karl Marx: "The Future Results of

British Rule in India" New-York Daily Tribune, August 8, 1853

There is no end to the violence and plunder which is called

British rule in India. Lenin: "Inflammable material in

world politics", 1908

In order to understand the partition of the sub-continent

and the terrible conditions it had to face it is necessary to identify the role

of imperialism in India and cover certain historical ground. For our present

purpose we are not concerned to follow in any detail the chronicle of British

rule in India, which would require a separate volume. We are concerned to bring

out some of the decisive forces of development which underlie the present

situation and its problem.

The burning question today is the present oppression and the

path of liberation. We are only concerned with the past in order to bring to

light the dynamic forces which still live in the present. The first to bring

this dynamic approach to Indian history, to turn the floodlight of scientific

method on to the social driving forces of Indian development both before and

after British rule, and lay bare alike the destructive role of British rule in

India and its regenerative or revolutionizing significance for the future, was

the founder of modern socialism, Karl Marx.

Marx’s well known articles on India, written in a series in

1853, are among the most fertile of his writings, and the starting point of

modern thought on the question of imperialism. Marx’s writing show the

distinctive problems of Asiatic economy, especially in India and China, the

effects of the impact of European capitalism upon it, and the conclusion to be

drawn for the future development as well as for the emancipation of the Indian

people. This close attention is given by some fifty references to India in

"Capital", and the many references in the Marx-Engels correspondence.

Marx’s analysis starts from the characteristics of "Asiatic

economy", which the impact of capitalism for the first time overthrew. "The key

to the whole East, is the absence of private property in Land", wrote Engels to

Marx in June 1853. The absence of private property in land is not originally

different from the primitive starting-point of European economy; the difference

lies in the subsequent development. Why, then did primitive communism in the

East not develop to landed property and feudalism, as in the West?

Climate

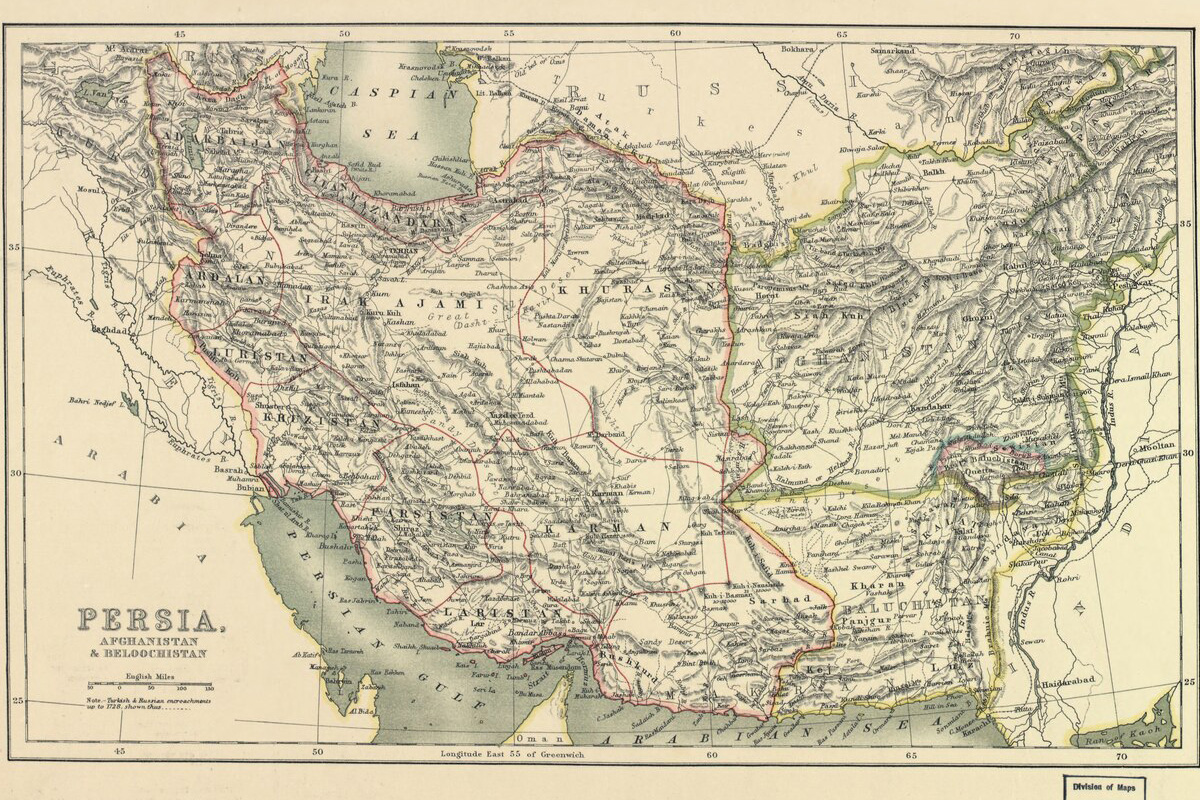

Engels suggests that the answer is to be found in the

climatic and geographical conditions: "How comes it that the Orientals did not

reach to landed property or feudalism? I think the reason lies principally in

the climate, combined with the conditions of the soil, especially the great

desert stretches which reach from the Sahara right through Arabia, Persia,

India and Tartary to the highest Asiatic uplands. Artificial irrigation is here

the first conditions of cultivation, and this is the concern either of the

communes, the Provinces or the Central Government" (Engels, letter to Marx,

June 6, 1853).

The conditions of cultivation were not compatible with

private property in land, and so arose the typical "Asiatic economy" of the remains

of primitive communism in the village system below, and the despotic central

government above, in charge of irrigation and public works, alongside war and

plunder. The understanding of the village system is thus the key to the

understanding of India. The classic description of the village system is

contained in "Capital":

"Those small and extremely ancient Indian communities, some

of which have continued down to this day, are based on possession in common of

the land, on the blending of agriculture and handicrafts, and on an unalterable

division of labour, which serves, whenever a new community is started, as a

plan and scheme ready cut and dried. Occupying areas of from 100 up to several

thousand acres, each forms a compact whole producing all it requires. The chief

part of the products is destined for direct use by the community itself, and

does not take the form of a commodity. Hence, production here is independent of

that division of labour brought about, in Indian society as a whole, by means

of the exchange of commodities. It is the surplus alone that becomes a

commodity, and a portion of even that, not until it has reached the hands of

the State, into whose hands from time immemorial a certain quantity of these

products has found its way in the shape of rent in kind. The constitution of

these communities varies in different parts of India…

‘This dozen of individuals is maintained at the expense of

the whole community. If the population increases, a new community is founded,

on the pattern of the old one, on unoccupied land. The whole mechanism

discloses a systematic division of labour; but a division like that in

manufactures is impossible, since the smith and the carpenter, & Co, find

an unchanging market, and at the most there occur, according to the sizes of

the villages, two or three of each, instead of one. The law that regulates the

division of labour in the community acts with the irresistible authority of a

law of Nature, at the same time that each individual artificer, the smith, the

carpenter, and so on, conducts in his workshop all the operations of his

handicraft in the traditional way, but independently, and without recognising

any authority over him. The simplicity of the organisation for production in

these self-sufficing communities that constantly reproduce themselves in the

same form, and when accidentally destroyed, spring up again on the spot and

with the same name this simplicity supplies the key to the secret of the

unchangeableness of Asiatic societies, an unchangeableness in such striking

contrast with the constant dissolution and refounding of Asiatic States, and

the never-ceasing changes of dynasty. The structure of the economic elements of

society remains untouched by the storm-clouds of the political sky". (Capital,

Vol 1, ch14, sec 4)

This is the traditional Indian economy which was shattered

in its foundations by the onset of foreign capitalism, represented by British

rule. Herein the British conquest differed from every previous conquest, in

that, while the previous foreign conquerors left untouched the economic basis

and eventually grew into its structure, the British conquest shattered that

basis and remained a foreign force, acting from outside and withdrawing its

tribute outside. Herein also the victory of foreign capitalism in India

differed from victory of capitalism in Europe, in that the destructive process

was not accompanied by any corresponding growth of new forces.

"All the civil wars, invasions, revolutions, conquests,

famines, strangely complex, rapid, and destructive as the successive action in

Hindostan may appear, did not go deeper than its surface. England has broken

down the entire framework of Indian society, without any symptoms of

reconstitution yet appearing. This loss of his old world, with no gain of a new

one, imparts a particular kind of melancholy to the present misery of the

Hindoo, and separates Hindostan, ruled by Britain, from all its ancient

traditions, and from the whole of its past history" (Marx "The British Rule in India", New-York Daily Tribune, June

25, 1853)

Destructive role

Marx traced with careful attention, distinguishing between

the earlier period of the monopoly of the East India Company up to 1813, and

the later period, after 1813, when the monopoly was broken and the invasion of

industrial capitalist manufactures overran India and completed the work. In the

earlier period the initial steps of destruction were accomplished:

1) By the East India Company’s colossal direct plunder. The

treasures transported from India to England were gained much less by the

comparatively insignificant commerce, than by the direct exploitation of that

country and by the colossal fortunes extorted and transmitted to England;

2) By the neglect of irrigation and public works, which now

allowed to fall into neglect;

3) By the introduction of English land system, private

property in land, with sale and alienation, and the whole English criminal

code;

4) By the direct prohibition or heavy duties on the import

of Indian manufactures, first into England, and later also Europe.

All this did not give the final blow. That came with the era

of nineteenth century capitalism. It was only after 1813, with the invasion of

English industrial manufactures, that the decisive wrecking of the Indian

economic structures took place. The effect of this wrecking during the first

half of the nineteenth century Marx traced with formidable facts.

Between 1780 and 1850 the total British exports to India

rose from £386,152 to £8,024,000; while the cotton manufacture in 1850 for which

the Indian market provided one-fourth of the foreign markets, employed

one-eighth of the population of Britain and contributed one-twelfth of the

whole national revenue.

"From 1818 to 1836 the export of twist from Great Britain to

India rose in the proportion of 1 to 5,200. In 1824 the export of British

muslins to India hardly amounted to 1,000,000 yards, while in 1837 it surpassed

64,000,000 of yards. But at the same time the population of Dacca decreased

from 150,000 inhabitants to 20,000. This decline of Indian towns celebrated for

their fabrics was by no means the worst consequence. British steam and science

uprooted, over the whole surface of Hindostan, the union between agriculture

and manufacturing industry". (Marx, The British Rule of India-in the New-York

Daily Tribune, June 25, 1853).

The handloom and spinning wheel were the pivots of the old

Indian society. The village system was based on agricultural union. British

capitalism not only destroyed the old manufacturing towns, driving their population

to the crowded village, but destroyed the balance of economic life in villages.

From this arose the desperate overpressure on agriculture. At the same time the

merciless extraction of the maximum revenue from the cultivators, without

giving any return for necessary expansion and works prevented agricultural

development.

Does Marx shed tears over the fall of the village system and

the destruction of the old basis of Indian society? Marx saw the infinite

suffering caused by the bourgeois social revolution, as in every country, and

all the greater in India on account of its being carried through under such

conditions. But he saw also the deeply reactionary character of that village

system and the indispensable necessity of its destruction if mankind is to

advance. Marx’s words lose none of their force today for those who, in India as

in Europe, seek to fight British rule by appealing for the revival of the

vanished pre-British India of the spinning wheel and the handloom.

"Now, sickening as it must be to human feeling to witness

those myriads of industrious patriarchal and inoffensive social organizations

disorganized and dissolved into their units, thrown into a sea of woes, and

their individual members losing at the same time their ancient form of civilization,

and their hereditary means of subsistence, we must not forget that these

idyllic village-communities, inoffensive though they may appear, had always

been the solid foundation of Oriental despotism, that they restrained the human

mind within the smallest possible compass, making it the unresisting tool of

superstition, enslaving it beneath traditional rules, depriving it of all

grandeur and historical energies.

"We must not forget the barbarian egotism which,

concentrating on some miserable patch of land, had quietly witnessed the ruin

of empires, the perpetration of unspeakable cruelties, the massacre of the

population of large towns, with no other consideration bestowed upon them than

on natural events, itself the helpless prey of any aggressor who deigned to

notice it at all. We must not forget that this undignified, stagnatory, and

vegetative life, that this passive sort of existence evoked on the other part,

in contradistinction, wild, aimless, unbounded forces of destruction and

rendered murder itself a religious rite in Hindostan. We must not forget that

these little communities were contaminated by distinctions of caste and by

slavery, that they subjugated man to external circumstances instead of

elevating man the sovereign of circumstances, that they transformed a

self-developing social state into never changing natural destiny, and thus

brought about a brutalizing worship of nature, exhibiting its degradation in

the fact that man, the sovereign of nature, fell down on his knees in adoration

of Kanuman, the monkey, and Sabbala, the cow".

"England, it is true, in causing a social revolution in

Hindostan, was actuated only by the vilest interests, and was stupid in her

manner of enforcing them. But that is not the question. The question is, can mankind

fulfil its destiny without a fundamental revolution in the social state of

Asia? If not, whatever may have been the crimes of England she was the

unconscious tool of history in bringing about that revolution" (Marx-The

British Rule in India, New-York Daily Tribune, June 25, 1853).

British Rule in India

England in Marx’s view had a double mission in India. One,

destructive, the other regenerating-the annihilation of the old Asiatic

society, and the laying of the material foundations of western society in Asia.

So far the destructive side had been mainly visible; nevertheless the work of

regeneration had begun.

Wherein did Marx see the beginning of such regeneration? He

gives numerous indications: political unity…more consolidated and extending

further than ever it did under the Mogul rule and destined to be strengthened

and perpetuated by the electric telegraph; Strengthening of the British

military control; free press, introduced for the first time into the Asiatic

society; the establishment of the private property in land – the great

desideratum of the Asiatic society; building up, however reluctantly and

sparingly, of an educated Indian class imbued with European science; regular

and rapid communication with Europe through Steam transport.

More important than all these was the inevitable consequence

of industrial capitalist exploitation of India. In order to develop the Indian

market, it was essential to secure the transformation of India into a

reproductive country–that is the source of raw materials to be exported in

order for the imported manufactured goods. This made necessary the development

of railways, roads and irrigation. This new phase was only beginning at the

time when Marx wrote. From the consequences of this new development Marx made the

prophecy which is the most famous of his declaration on India:

"Know that the English millocracy intend to endow India with

railways with the exclusive view of extracting at diminished expenses the

cotton and other raw materials for their manufactures. But when you have once

introduced machinery into the locomotion of a country, which possesses iron and

coals, you are unable to withhold it from its fabrication. You cannot maintain

a net of railways over an immense country without introducing all those industrial

processes necessary to meet the immediate and current wants of railway

locomotion, and out of which there must grow the application of machinery to

those branches of industry not immediately connected with railways. The

railway-system will therefore become, in India, truly the forerunner of modern

industry….. Modern industry, resulting from the railway system, will dissolve

the hereditary divisions of labour, upon which rest the Indian castes, those

decisive impediments to Indian progress and Indian power." (Marx, The Future

Results of British Rule in India, New-York Daily Tribune, August 8, 1853).

Does this mean that Marx saw imperialism in India as a

progressive force capable of emancipating the Indian people and carrying them

forward along the path of social progress? On the contrary. He made clear that

imperialism was laying down the material conditions for new advance. But that

new advance could only be realised by the Indian people themselves on

conditions that they won liberation from imperialist rule, either by their own

successful revolt, or by the victory of the industrial working class in

Britain, carrying with it the liberation of the Indian people. Until then, all

material achievements of imperialism in India could bring no benefit or improvement

of conditions to the Indian people.

Marx’s analysis of the Indian situation up to the middle of

the nineteenth century turns on three factors:

1) The destructive role of the British rule in India,

uprooting the old society;

2) The regenerative role of British rule in India in the

period of free-trade capitalism, laying down the material premises for the

future new society

3) The consequent practical conclusion of the necessity of a

political transformation whereby the Indian people should free themselves from

imperialist rule in order to build the new society.

Today imperialism all over the world has outlived its

objectively progressive role, corresponding to the role of capitalism, and has

become the most powerful reactionary force in the Indian sub-continent,

strengthening all the other forms of Indian reaction. The stage has thus been

reached when the task of the political transformation indicated by Marx is

directly on the order of the day.

See also: The Crime of Partition – part 2