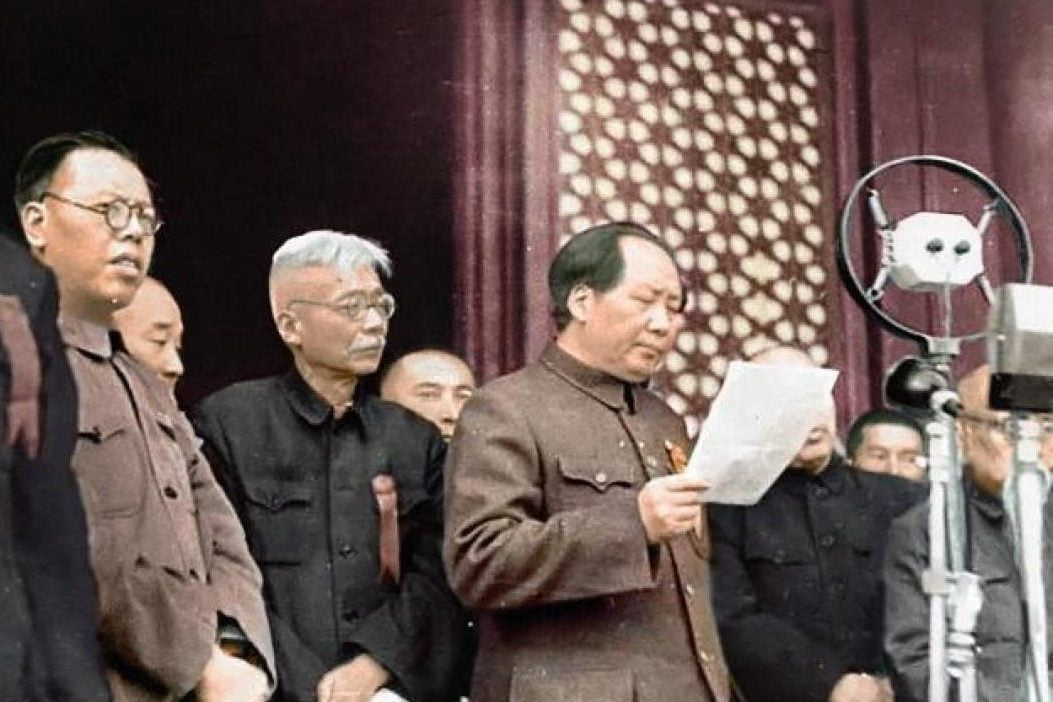

On 1 October 1949, Mao Zedong, leader of the Chinese Communist Party, proclaimed the People’s Republic of China.

For Marxists, the Chinese Revolution of 1949 was the second greatest event in human history, second only to the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

The revolutionary Chinese masses took matters into their own hands, changing world history for ever. Millions of peasants and workers, who had hitherto been brutally exploited by the landlords and capitalists, threw off the humiliating yoke of imperialism and capitalism.

In this article, based on one written 10 years ago, Alan Woods explains the processes surrounding these inspiring revolutionary events.

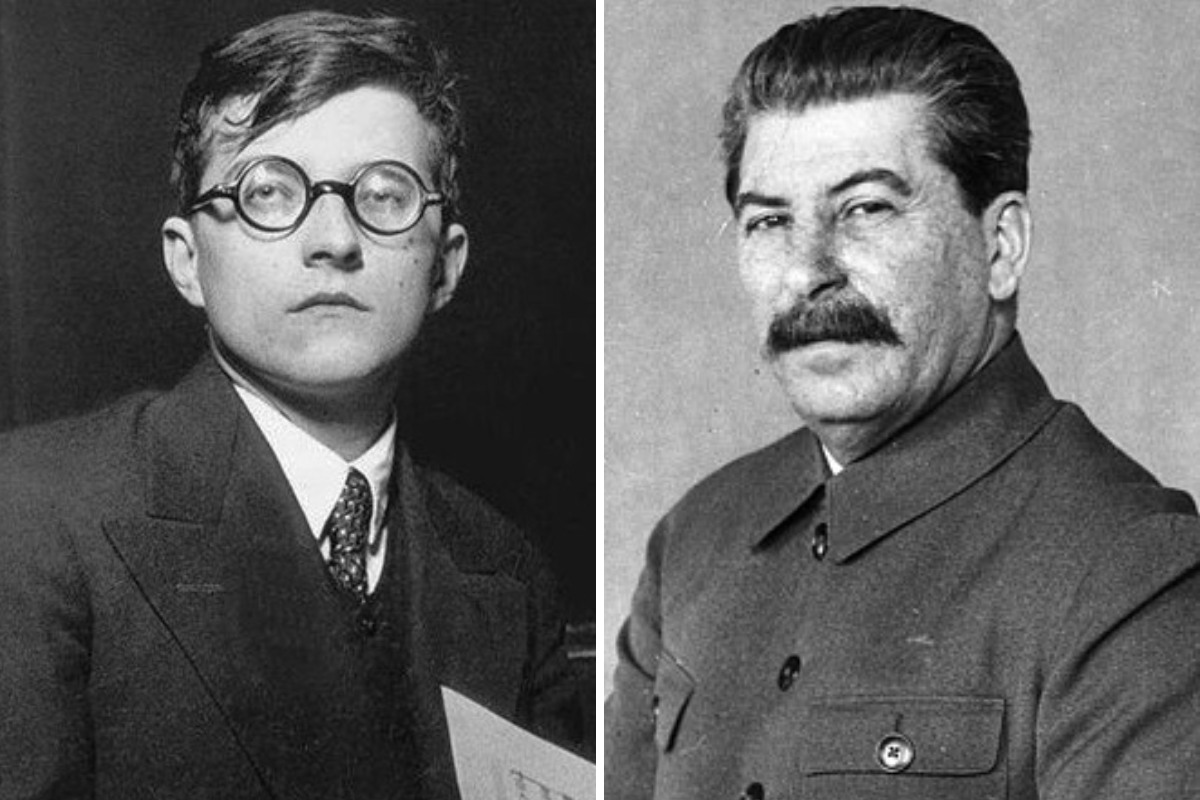

The first Chinese Revolution of 1925-7 had been a genuine proletarian revolution. But it was aborted by the false policies of Stalin and Bukharin, who subordinated the Chinese working class to the so-called democratic bourgeoisie under Chiang Kai-shek. The Chinese Communist Party was dissolved into the bourgeois Kuomintang (KMT) and Stalin even invited Chiang Kai-shek to be a member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International.

This disastrous policy led to a catastrophic defeat in 1927 when the “bourgeois democrat” Chiang Kai-shek organised the massacre of the Communists in Shanghai. The smashing of the Chinese working class determined the character of the Chinese Revolution subsequently. The remnants of the Communist Party fled to the countryside, where they began to organize guerrilla war based on the peasantry. This fundamentally changed the course of the Revolution.

The Revolution of 1949 succeeded because of the complete blind alley of landlordism and capitalism in China. Chiang Kai-shek had two decades after 1927 to show what he could do. But in the end, China was as dependent on imperialism as ever, the agrarian problem remained unsolved and China remained a backward, semi-feudal and semi-colonial country. The Chinese bourgeoisie, together with all the other propertied classes, was entangled with imperialism, forming a reactionary bloc opposed to change.

Manchuria

The rottenness of the Chinese bourgeoisie was exposed when the Japanese imperialists invaded Manchuria in 1931. During the struggle to defeat the Japanese invaders, the Chinese Communists offered a united front to the bourgeois-nationalists of the Kuomintang led by Chiang Kai-shek. But, in reality, the level of actual cooperation between Mao’s forces and the KMT was minimal. The alliance was a united front in name only.

The Communists assumed the lion’s share of the fighting against the Japanese. The KMT forces were always far more concerned with the fight against the Reds. In December 1940, Chiang Kai-shek demanded that the CPC’s New Fourth Army evacuate Anhui and Jiangsu Provinces. This led to major clashes between the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and Chiang’s forces and there were several thousand deaths. This signified the end of the so-called united front.

The Second World War ended with the enormous strengthening of US imperialism and of Stalin’s Russia, and the inevitable conflict between them was already becoming evident. On August 9, 1945, Soviet forces launched the impressive Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation to attack the Japanese in Manchuria and along the Chinese-Mongolian border. In a lightning campaign the Soviet army smashed the Japanese army and occupied Manchuria. 700,000 Japanese troops stationed in the region surrendered, and the Red Army conquered Manchukuo, Mengjiang (inner Mongolia), northern Korea, southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands.

The rapid defeat of Japan’s Kwantung Army by the Red Army is not mentioned by anybody nowadays. But it was a significant factor in Japan’s surrender and the termination of World War II. It was also a significant element in Washington’s calculations in Asia. The US imperialists feared that the Soviet Red Army would march straight through China and enter Japan itself, just as it had previously advanced through Eastern Europe. Japan finally surrendered to the USA after the US dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The main purpose of wiping out these Japanese cities was to show Stalin that the USA now possessed a new and terrifying weapon in its arsenal.

USA and Russia

Under the terms of the Japanese unconditional surrender dictated by the United States, Japanese troops were ordered to surrender to Chiang’s troops and not to the Communists in the occupied areas of China. Chiang Kai-shek ordered the Japanese troops to remain at their post to receive the Kuomintang and not surrender their arms to the Communists.

After the Japanese surrender, US President Truman was very clear about what he described as “using the Japanese to hold off the Communists”. In his memoirs he writes:

“It was perfectly clear to us that if we told the Japanese to lay down their arms immediately and march to the seaboard, the entire country would be taken over by the Communists. We therefore had to take the unusual step of using the enemy as a garrison…”

What was the position of Moscow in all this? Initially the Red Army allowed the PLA to strengthen its positions in Manchuria. But by November 1945, they reversed their stance. Chiang Kai-shek and the US imperialists were terrified at the prospect of a Communist takeover of Manchuria after the Soviet departure. He therefore made a deal with Moscow to delay their withdrawal until he had moved enough of his best-trained men and modern material into the region. KMT troops were then airlifted to the region in United States aircraft. The Russians then allowed them to occupy key cities in North China, while the countryside was left under the control of the CPC.

In reality, Stalin did not trust the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party and did not believe that they could succeed in taking power. Stalin urged Mao to join a coalition government with the Kuomintang, an idea that Mao originally accepted.

“While the war continued, Mao Tse-tung had been demanding that the Nationalists agree to the establishment of a coalition government to replace their one-party rule, and Stalin and Molotov had been saying that the two Chinese sides should get together.” (Edward E. Rice, Mao’s Way, p.114)

In the end, as was inevitable, negotiations broke down and the civil war resumed. The Soviet Union provided quite limited aid to the PLA, whereas the United States assisted the Nationalists with hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of military supplies and equipment.

The Americans had the ambition of making China a US sphere of influence (in effect a semi-colony) after the war. But after all the sufferings of the Second World War, the American people would not have been prepared to support a new war to subjugate China. More importantly, the American soldiers would not have been prepared to fight such a war. The inability of US imperialism to intervene against the Chinese Revolution was therefore an important element in the equation.

Demoralisation and desertion

In July 1946, with the active support of US imperialism, Chiang Kai-shek launched a counter-revolutionary offensive against the People’s Liberation Army. He had made careful preparations, and at that time he had approximately three and a half times as many troops as the PLA; and his material resources were far superior. He had access to modern industries and modern means of communication, which the People’s Liberation Army lacked. In theory, he should have had an easy victory. So how did Mao win?

What the US imperialists and Chiang Kai-shek failed to realise was that the most effective weapon in the hands of the PLA was not guns and tanks, but propaganda. They promised the landless and starving peasants that by fighting for the PLA they would be able to take farmland from their landlords. In most cases, the surrounding countryside and small towns had come under the control of the PLA long before the cities.

In every village the PLA distributed land to the peasants, but they always left a number of plots unoccupied – for the soldiers in Chiang Kai-shek’s army. This proved to be highly effective. Chiang’s army had probably the highest rate of desertion of any army in history. This meant that despite suffering heavy casualties, the PLA was able to keep fighting, with a constant supply of fresh recruits.

In theory, the Nationalists still had a big advantage over the PLA. On paper, they enjoyed a clear superiority in both numbers of men and weapons. They controlled a much larger territory and population than their adversaries, and enjoyed considerable international support from the USA and Western Europe. But that was only in theory. The reality on the ground was very different. The Nationalist forces suffered from a lack of morale and rampant corruption that greatly reduced their ability to fight, and their civilian support had collapsed.

The demoralized and undisciplined Nationalist troops were melting away in the face of the irresistible forward march of the People’s Liberation Army. They surrendered or fled, leaving their weapons behind.

The PLA was able to go onto the counteroffensive, forcing the Kuomintang to abandon its plan for a general offensive. The transformation of the military situation was really incredible. The PLA, which for years had been outnumbered, by July-December 1948 finally gained numerical superiority over the Kuomintang forces.

In January 1949, Beiping was taken by the PLA without a fight and its name was changed back to Beijing. On April 21, Mao’s forces crossed the Yangtze River and captured Nanjing, the KMT’s capital. Within a short space of time they were driving the disorganized and demoralized remnants of KMT forces southwards in southern China.

In the end, Chiang Kai-shek and approximately two million Nationalist Chinese – predominantly from the former government bureaucrats and businessmen – retreated from mainland China to the island of Taiwan (then known as Formosa). All this culminated on October 1, 1949, with Mao proclaiming the People’s Republic of China.

Bonapartism

Before the War, Trotsky had pointed out that the decisive question was what would happen when the Red Army entered the towns and cities. A genuine workers’ state would base itself on the working class and its organs of power: the soviets. It would encourage the self-organisation of the workers, with real trade unions, independent of the state.

However, the 1949 revolution in China was carried out in Bonapartist fashion from the top. Instead of basing themselves on the working class to overthrow the bourgeois state, they formed a coalition government composed of various factions of the former Kuomintang government. Far from encouraging the independent movement of the masses, any manifestations of independent action on the part of the workers was repressed.

Mao initially began with a programme that did not go beyond the limits of capitalism. He balanced between the bourgeoisie and the workers and peasants in order to consolidate the new state and concentrate power into his hands. In the first stages, he did everything to prevent the workers from taking power and crush whatever elements of an independent workers’ movement that had emerged.

Mao originally had the perspective of fifty or a hundred years of capitalism. He insisted that he would only expropriate “bureaucratic-capital”. But having taken power, Mao very soon realised that the rotten and corrupt Chinese bourgeoisie was incapable of playing any progressive role. Thus, leaning on the working class, he proceeded to nationalise the banks and all large-scale industry and to expropriate the landlords and capitalists.

Mao consolidated a new state, not as a direct expression of the working class but by balancing between the classes. And it was through this state that he expropriated the landlords and capitalists.

Stalinism and Maoism

In spite of the distorted manner in which it was achieved, the establishment of a nationalised planned economy was a progressive measure and a huge step forward for China. However, it was not a proletarian revolution in the sense understood by Marx and Lenin. The Chinese Stalinists, acting in the name of the proletariat, carried out the basic economic tasks of the socialist revolution, but the workers in China had been passive throughout the civil war and did not play an independent role in the whole process.

In spite of the distorted manner in which it was achieved, the establishment of a nationalised planned economy was a progressive measure and a huge step forward for China. However, it was not a proletarian revolution in the sense understood by Marx and Lenin. The Chinese Stalinists, acting in the name of the proletariat, carried out the basic economic tasks of the socialist revolution, but the workers in China had been passive throughout the civil war and did not play an independent role in the whole process.

The bureaucracy developed a totalitarian one-party dictatorship, modelled on Stalin’s Russia. Given the way the revolution was carried out, and the existence of a mighty Stalinist regime on China’s borders, this outcome was entirely predictable.

The only armed force in China was the PLA, the peasant army controlled by the Chinese Stalinists. Lenin explained that the state, in the last analysis, is armed bodies of men. By 1949 the CPC claimed a membership of 4.5 million, 90% of whom were peasants. Mao was the Party Chairman and really held the reins of power in his hands, although the government was formally headed by his right-hand-man, Zhou En-lai. The army, police and secret police were all in their hands. That is just another way of saying: they held state power. This was their real power base, and this was decisive.

Mao used the peasant army as a battering ram to smash the old state. But the peasantry is a class that is least capable of acquiring a socialist consciousness. Of course, in underdeveloped colonial and semi-colonial nations, the peasantry must play a very important role – but it can only be an auxiliary role, subordinated to the revolutionary movement of the workers in the cities.

We should remember that up to the Russian Revolution even Lenin denied the possibility of “the victory of the proletarian revolution in a backward country”. Only Trotsky had previously advanced the perspective that the Russian working class could come to power before the proletariat of Western Europe. However, in 1917 that is precisely what happened. The Bolshevik Party, under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, led the workers to power in Russia, which, like China in 1949, was an extremely backward, semi-feudal country. The Russian working class, which was a small minority of society (the majority were peasants), placed itself at the head of society and carried out a classical socialist revolution in October 1917.

Under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, the proletariat immediately carried out the tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution, and then carried on to expropriate the capitalists and established a regime of workers’ democracy. It would have been possible for the Chinese Revolution to have developed on the same lines as the October Revolution in Russia. What was lacking was the subjective factor: the Bolshevik Party of Lenin and Trotsky.

The kind of regime established in China represented a deviation from the classical norm. But, in real life, processes do not always conform to the ideal norms. All kinds of distortions and peculiar variants are possible. Ted Grant was the only Marxist theoretician who explained the role of proletarian Bonapartism as a peculiar variant of Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution. When Mao’s perspective was still that of a long period of capitalism, Ted explained in 1949 the inevitability of Mao’s victory and the establishment of a deformed workers’ state.

Revolutionary traditions

The Chinese Revolution was a giant step forward. If it had not succeeded, the country would undoubtedly have been transformed into a semi-colony of US imperialism under the dictatorship of Chiang Kai-shek. Instead, seventy years ago, the Chinese people for the first time achieved full emancipation from foreign rule.

The abolition of landlordism freed China from the burden of semi-feudal relations and the liquidation of private ownership of industry and the introduction of the state monopoly of foreign trade gave a powerful impetus to the development of Chinese industry. However, the nationalisation of the means of production is not yet socialism, although it is the prior condition for it.

The movement towards socialism requires the control, guidance and participation of the proletariat. The uncontrolled rule of a privileged elite is not compatible with genuine socialism. It will produce all sorts of new contradictions. Bureaucratic control signifies corruption, nepotism, waste, mismanagement and chaos, which eventually undermine the gains of a nationalised planned economy. The experience of both Russia and China prove this.

The leading stratum has now led China down the road of capitalism. This possibility was always implicit in a situation where the bureaucracy had raised itself above society. Starting initially as measures to stimulate economic growth within the planned economy, the bureaucracy has adopted capitalist methods.

However, in spite of the growth, the imposition of ‘market economics’ in China does not serve the interests of the Chinese workers and peasants. It is creating new and terrible contradictions, both in the towns and villages. At a certain point, these will lead to a new revolutionary upsurge.

On the basis of experience, the Chinese workers, peasants, and students will rediscover the great revolutionary traditions of the past. The new generation will embrace the ideas of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Trotsky and Chen Duxiu – the founder of Chinese Communism and its true heir.

The growing wave of strikes and protests seen across the country is a sign of the explosive events that are coming. And when the sleeping giant of the Chinese working class awakens, the whole world will feel its tremors.