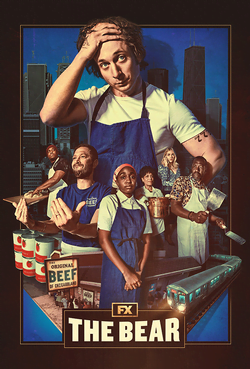

The latest ‘prestige television’ hit, The Bear, has been widely lauded as the best TV show around, now that Succession is over.

Whilst there’s no doubt that The Bear is well made and acted, beautifully shot, and has believable and likeable characters, these positives ultimately serve to deliver a story that expresses petty-bourgeois contempt for the working class.

Plot and protagonist

The set up of the series revolves around Carmen, who is left his brother’s Italian American restaurant after he commits suicide.

As a result, our protagonist abandons his position as a leading chef at a world-renowned restaurant, in order to keep his brother’s place going. This traditional restaurant is presented as being just as worn out, ramshackle, and toxic as its now dead former owner.

The arc is clear: Carmen must overcome his family’s deep-seated problems and self-destructive nature, by transforming the mess of a restaurant his brother left him. The restaurant’s chaos clearly expresses the chaos of his family.

This story, compelling enough to watch unfold, is told very much from the perspective of restaurant owners. The establishment he inherits, and the family he comes from, are believably presented. There are many places and families like that.

The direction the show takes implies that this is a world to be escaped, or transformed into something better. All the industry’s stresses and obstacles are seen from the point of view of a frustrated petty bourgeois with aspirations to break free of their more humble beginnings.

All the characters go on a journey, starting as likeable but narrow minded and self-destructive, and eventually becoming enlightened.

Resistant to change

In the second (and most recent) series, Carmen has turned the ship around. But he is not satisfied. He wants to turn it into his own ‘fine dining’ establishment in Chicago.

The struggle is to get all this done on the very tight schedule required by their investor – a family friend who is always portrayed as helpful, flexible, and understanding, if a little bit of a ball buster. The associated stresses in meeting this schedule serve to bring to the surface deep-seated tensions and unresolved family problems.

The meaning of the show is encapsulated not by its two main characters, but by Richie, who not only managed the restaurant under Carmen’s brother, but was also his best friend. He therefore represents the restaurant’s outdated past, with all the toxicity and stubbornness that entails.

If the motor force of the story is the need to overcome the family and its restaurant’s bad ways, then Richie’s abrasive personality is essential to dramatising this.

At every turn, he opposes change. He unhelpfully butts in on others work, since he is insecure about his own role, lashing out at other staff and generally spreading stress.

His general method is to improvise shoddy solutions, to make things up as he goes along, and to not take himself or the restaurant seriously. We see how he papers over financial cracks, for example, by selling drugs in a back alley behind the restaurant.

Richie is portrayed as loveable, with his heart in the right place, but down-and-out, stuck in his ways, and badly in need of some self-awareness and self-respect.

Again, he is a realistic and likeable character. But by making it clear that he plays a negative role, and that this is entirely down to his flawed personal character, the viewer is led to the typical petty-bourgeois conclusion that working-class people are responsible for their own mess.

Personal growth

As they struggle with the high-class renovations of the restaurant in season two, Richie’s behaviour becomes such an obstacle that he is sent by Carmen to work in what we are told is the world’s best restaurant – presumably to learn how a serious, professional restaurant works.

At this restaurant, we see Richie being made to do nothing but polish forks for eight hours a day. If a fork has so much as a hint of dullness to it, he is upbraided by his new manager and made to do it again.

Later on, in a staff meeting, a manager berates the staff like schoolchildren, because none of them have owned up to causing a ‘smudge’ on a customer’s plate. This smudge is treated as a deplorable dropping of standards, almost enough to bring the restaurant into a crisis.

At this point, the audience feels strong sympathy for Richie’s view that this restaurant is full of ponces, making appalling demands on its staff. It is much to our surprise, then, when this pedantry is revealed to be a good thing.

Richie receives a stern talking to from his manager, who tells him that all these petty tasks and standards are ultimately for the love of the art of food, and are about having self-respect and self-discipline.

He is then given a more interesting task for the next day, and takes it upon himself to turn his life around. He turns up the next day on time, more smartly dressed, and determined to work hard and achieve something.

Richie never looks back. He is a changed man. He discovers that the restaurant is indeed an inspiring place to work; that the staff excel in this environment’s impeccable standards.

The staff are portrayed as in love with the food, and with the experience that their restaurant generates for its customers. They are energised by the goals they are set and the rigorous methods employed.

Richie returns to Carmen’s restaurant in a high-quality suit, which he is never seen out of again. He proudly declares ‘I wear suits now’. He makes a point of apologising to staff for his previous behaviour, in an act of admirable self-awareness.

At one point, his friend and fellow ‘old skool’ member of staff embarrassingly uses the same racial slur he himself used to make. Richie makes a point of calmly telling off this “problematic individual”, as he calls him.

Richie’s journey is clearly told from the point of view of a frustrated business owner. He is portrayed as a typical working-class guy, as they would see it: slovenly, stubborn, lazy, a troublemaker, uneducated, and prone to faux pas. He is ‘problematic’.

He is able to overcome these poor traits and attain self-awareness, by becoming more middle class: wearing suits, being hard working and professional, and certainly not saying ‘problematic’ things. All of this is portrayed as a very good thing; as personal growth.

‘Enlightened’ professionals

The same point is revealed not only in the story of Richie, but also that of junior chef Tina.

Like Richie, Tina worked in the restaurant under the previous management. Like him, she resists change – even going so far as to sabotage the efforts of a new chef hired by Carmen.

Tina is clearly a working-class Latina. The depiction is rather stereotypical: she is uneducated and stuck in her ways; narrow minded and difficult. She masks her insecurity with rudeness to her superiors. This is how the ‘enlightened’ petty bourgeoisie sees the working class.

But Tina is shown attention by Carmen and his chef ally Sydney. He takes the time to show her his more professional ways; the superiority of his higher standards. And she comes to appreciate the respect she is duly shown.

In the second season, Carmen pays for her to go to a high-class culinary school, and gifts her some very expensive sharp knives. She is elevated by this. She becomes a calmer person, and is very much on board with the project.

This is exactly how a successful, ‘enlightened’ petty bourgeois likes to see themselves: showing the working class ‘the way’; lifting them up; helping them to attain a better life.

Confines of capitalism

The show does have a certain undeniable success with Richie’s story line. Undoubtedly, many small, lower-cost establishments like the one Richie comes from will have chaotic, unprofessional, and unhealthy ways of working. And indeed, the food that working-class people can afford under capitalism is generally of lower quality – using poor produce, unhealthy, and often badly cooked.

Thus, some of the methods that Richie learns here, the seriousness and the appreciation for quality, are needed for himself and for his restaurant.

The trouble is that, within the confines of capitalism, any serious effort to improve on these low standards, as Carmen is attempting, inevitably takes a restaurant into the domain of a different class.

Similarly, working-class districts are typically run down. Housing is run down; roads are polluted; and poverty is pervasive – all of which encourages crime. This is particularly the case in a city like Chicago, which has areas of acute poverty and crime.

But as we all know, the only way capitalism can ‘resolve’ such problems is through gentrification, which leads to higher prices and the cultivation of an exclusive atmosphere.

Neither dilapidation nor gentrification are acceptable. But they are all that capitalism has to offer. The Bear is essentially about the struggle to ‘improve’ an area by gentrifying it.

Competition and exploitation

The show’s depiction of the high end of the restaurant industry is also extremely naïve. And, once again, it is clearly from the perspective of an owner.

Yes, the pedantic and harsh standards of a Michelin-starred restaurant are shown. It is admitted to be a stressful environment – but ultimately one that is good for its staff, who thrive when given clear tasks and high standards.

Of course, many talented chefs do love making excellent food, something which should not be the preserve of the rich. But the nature of capitalism forces such chefs to run their restaurants in certain ways, whether they like it or not.

In reality, ‘fine dining’ establishments are notorious for not even paying vast swathes of their staff, treating them like slaves. Those who are paid are typically on very low wages.

According to the Financial Times, before the pandemic, ‘world no1 restaurant’ Noma only paid about half of its chefs, the rest being ‘interns’. Despite this, it is ludicrously expensive, at around £500 per person.

Noma is now closing, complaining that it cannot afford to stay in business after having agreed to pay all of its staff. It will instead cash in on its brand name and become a shop, selling 250ml bottles of sauce for £30.

The world of fine dining is all about branding. Carmen’s mission is to get that brand recognition for his new restaurant – obtaining a Michelin star and thereby completely obliterating what it once was. Once a head chef has secured that kind of international reputation, they can make a lot of money (and exploit a lot of interns desperate for a way into the industry).

Perhaps, like Carmen, they started out wanting only to do amazing things with food, for its own sake. But the process of doing so in a competitive international market will inevitably force them to adapt their menus to be as luxurious and attention grabbing as possible, which in turn leads to astronomical prices.

Out of reach

As if to ward off the audience’s likely criticisms that these restaurants are far too expensive and out of reach for ordinary Chicagoans, we are made to see that the chef’s passion for the experience (and not the money) shines through.

At the Michelin-starred restaurant Richie interns at, we are told that the staff have discovered that one of that evening’s diners has been saving up for months to go there. The staff agree to surprise these customers by gifting them the meal, purely out of sympathy for their economic constraints, and to blow their minds with how wonderful an experience it is.

The message is clear: these restaurants are not about the money, but love for food.

Later on, Richie overhears that some other customers have never tried Chicago’s famous ‘deep dish’ pizza. And so the manager sends him to secretly pick one up from elsewhere. The head chef then lovingly turns it into an even more special, ‘haute cuisine’ version of ‘deep dish’. The diners are then surprised with this treat. And once again, their minds are blown by the attentiveness and sheer joy of this restaurant.

At one point Richie stumbles across a woman working at an unsocial hour, all on her own in the kitchen. She is tediously peeling a gigantic pile of mushrooms. As he talks to her, she is revealed to be a charming and insightful woman, who helps Richie to understand himself.

It turns out that she is actually the owner of this world-leading restaurant, but she takes the time to perform tasks like this to keep herself grounded. In other words, the hierarchy of this elite restaurant is merely one of moral authority. The chefs and owners have earned their places through honest hard work. And they still muck in, and are not above sharing their life stories to even the newest worker.

In reality, it is widely known that those who intern – for free, at top restaurants – are left to do the tedious work on a production line by themselves. They almost never see the celebrity chefs, let alone work side-by-side with them whilst having heart-warming chats.

Hardship and pressures

In the end, Carmen manages to meet the demands of his investor and open on time. The capitalist pressure to do so is presented as stressful, but ultimately positive – a spurring on to great things.

Nothing is said about the fact the prices of this former working-class eatery have spiralled, or about how the new restaurant has absolutely nothing to do with its roots. Not only the food, but also the decor and layout are completely different. It ends up looking just like any other trendy restaurant serving wealthy people.

The reason this justification for gentrification is presented as a heart-warming story of personal growth, of overcoming mental health challenges and a difficult family, is because that is how the successful petty bourgeoisie sees it: their success is because of their own hard work and dedication to being better people.

These ladies and gentlemen see the difficulties of working-class life as owing to the psychological flaws of its members, and not the objective hardship their class position throws at them.

And ultimately, The Bear is a highly rated show because those doing the ratings share this mindset.