In the second part of our article on the 1944 apprentices’ strike, we publish a short question and answer session between Socialist Appeal supporters and Bill Landles, dealing with the Worker’s International League and its involvement in the apprentices’ strike, and the trial which followed.

In the second part of our article on the 1944 apprentices’ strike, we publish a short question and answer session between Socialist Appeal supporters and Bill Landles, dealing with the Worker’s International League and its involvement in the apprentices’ strike, and the trial which followed.

The Worker’s International League, founded by Ted Grant and other British Marxists in 1938, was the predecessor to Socialist Appeal and the Militant Tendency, active during World War Two. It was a sympathetic section of the Fourth International, and was later joined by the Revolutionary Socialist League in March of 1944 to become the Revolutionary Communist Party. It is from these groups, the Workers International League and later the Revolutionary Communist Party, upon which our tradition has been built.

Socialist Appeal: One of the things that I was quite surprised to find out about was just how many copies of Socialist Appeal (the paper of the WIL) were sold during the war considering the rationing of paper. Would you be able to tell us a little about the Worker’s International League at the time? It seems as though it was a very serious organisation with some deep roots in the class. You also mentioned the trial of the members of the WIL involved in supporting the apprentices’ strike. Could you tell us a little bit more about how you got involved with the WIL and how that developed in terms of their intervention in the dispute?

Bill Landles: The Workers International League was very serious indeed and contact was made between the apprentices and the WIL because initially Bill Davy had, in looking around to see where we could get support, come across this name Roy Tearse, who at that time was the industrial organiser of the WIL, so that was the initial contact. He was contacted and had discussions with Bill Davy and was able to give advice on various things, like the preparations of leaflets, who we should try to get in touch with, how we should raise money and so on. But it so happened also that that the WIL had two comrades who actually lived on Tyneside. One was Heaton Lee, and also his partner Anne Keen, and they were local people. So we had approached them as well and they were willing to help in the preparation of leaflets, to do some typing and in fact in any way to help our endeavours as far as the strike was concerned.

Now the WIL organisation, which was a national organisation at the time, had taken a leading part in fact in many of the activities and struggles of the class, and during the War their paper, the Socialist Appeal, had a circulation of about 20,000. So they had some very deep roots in the class and had been instrumental very often in being able to give leadership and help raise funds and publicise the activities of the class when they went into struggle.

Later on, these same people, who had supported our strike, were actually arrested under the 1927 Trade Union Trade Disputes Act. At the time of the strike the right-wing press and the trade union bureaucrats attempted to persuade the public that the strike had actually been festered and fostered by these Trotskyists, but nothing could be further from the truth. The strike itself, as I’ve already illustrated, was in fact the immediate response of young people to this legislation [The Bevan Ballot scheme], so although the WIL was involved from the point of view of being sympathetic to the strike, and willing to do what they could to further the aims of the apprentices in that strike, they certainly in no way could possibly have been accused of being agitators who were agitating for strikes.

They were viciously attacked both by the press, by the government, and by the trade union leadership for this activity, and the level of the attacks upon them really reflected the fact that there was an awareness that the WIL were in fact simply echoing the basic wishes and demands of the actual class itself. So to that extent they were supportive, but in no way were they responsible for any of the ridiculous claims made by the right-wing press.

After the strike, the police raided the houses of a number of people all over the country, including the local people who had helped us – Anne Keen and Heaton Lee. At 3am there were knocks on the door, and every single document, the typewriter – everything was removed from the premises. They were later, together with Roy Tearse and Jock Haston, arrested and charged under the 1927 Trade Union Trade Disputes Act. This Act essentially stated that it is unlawful to act in furtherance of a strike. It’s actually quite funny, but Jock Haston managed to avoid the police in the first instance by going to the pictures, strangely enough, because he happened to be in Edinburgh at the time. He did actually later go into a police station after having been to the pictures and said, “I’m Jock Haston, you’re looking for me!” At which point they took him into custody.

In the trial, the prosecution actually felt that they could use the apprentices’ representatives as part of showing that these Trotskyists were influential in causing the strike. I was interviewed personally. At work, one morning after the strike, after having gone back to work, I was approached by the foreman and told to go down to an office where somebody wanted to see me. So I went down there and there were two persons in the room who were both either special branch or MI5, I’m not sure which, but they then asked me all kinds of questions about the strike which I answered to the best of my ability. They had gone around to speak with at least another 20 apprentices.

When it came to the actual trial, the prosecution had in fact called upon 11 apprentices to give evidence on behalf of the prosecution. And out of that 11, when the prosecution put the witnesses in the box and cross questioned them, somewhat to their surprise, they found that every apprentice that they questioned made comments, remarks, and answers which in fact showed quite conclusively that they had not in any way been influenced by Trotskyists, or anybody else for that matter.

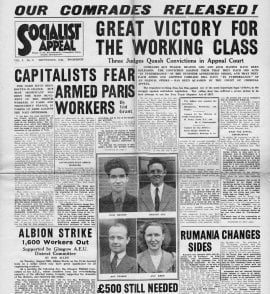

I remember that when I was questioned I was asked about the strike. My replies were simply that we came out on strike because we didn’t think that conscription was going to solve the problem, and that our particular policy on that issue was to nationalise the mines. This kind or response to the prosecution meant that the case was considerably weakened, to the extent that, out of all of the counts brought by the prosecution, I think that only two of them were actually sustained by the Jury. Unfortunately that in itself was enough to find them guilty, and two of them were sentenced to twelve months – that was Roy Tearse and Jock Haston. Heaton Lee got six months and Anne Keen was sentenced I think to 13 days, but as she had already been arrested and had spent time in prison before they had appeared, she was released straight away.

The prosecution really hadn’t done their homework very well in a sense because, with the support of a number of left leaning MPs, who were involved in the Anti-Labour Laws Victims Defence Committee that was set up by the WIL/RCP, money had been raised, and we were able to mount an appeal in the High Court straight away. The High Court heard the case, and during the trial they pointed out that it should never have been brought before any court of law because the 1927 Trades Disputes Act applies only to any activity in the furtherance of a strike; but in actual fact the activities which the prosecution had highlighted were those which had taken place before the strike was under way. The helping with leaflets and things like that were done before the strike actually took place, so the prosecution had themselves misunderstood the 1927 Trades Union Trades Disputes Act, and the appeal court had no option but to quash the sentences, and the three who were still in prison were immediately released. They then went back to what their normal activities in life had been at the time.

Socialist Appeal: You remained politically active after the apprentices strike and joined the WIL. Could you tell us a little bit about the fusion of the WIL and the RSL (Revolutionary Socialist League) to become the Revolutionary Communist Party (the official British section of the Fourth International)?

BL: At the time, as you say, these two groups, the Workers International League and the RSL (Revolutionary Socialist League) – two separate factions – did come together and unite under the new title of the Revolutionary Communist Party. That must have been later on in ’44.

[Editor’s note: before the unification, the WIL described itself as a sympathetic section of the Fourth International whilst the RSL was the official British section, recognised by the International. The Fourth International continuously made calls on both sections to unify, but WIL comrades would only agree to unity on a principled basis. This was achieved in 1944 when, after a period of degeneration (both political and organisational) of the RSL, it agreed to dissolve itself into the WIL, which had continued to grow throughout the war and proved itself the only real representative of Trotsky’s ideas within Britain, thus making a unified formation, which became the official British section of the Fourth International.]

Jock Haston had come up to what was our branch meeting. By then I was a committed member of the organisation, which is not surprising really because my father worked down the pits, and I well-remembered the days when they were supposed to be working and very often the pits were just made idle depending on the rate of profit that the coal owners were making at any particular time. This meant that the workers were sent home with no work to do, unable to earn a living. And during the 30s I lived in a family which was familiar with the conditions in the pits. I doubt whether you’d use the expression in those days, but we were in fact socialists and left wingers, so that it was almost automatic really that I would gravitate as an individual towards left-wing politics. Due to this, I became a member of the Revolutionary Communist Party.

At that time we actually even stood Herbie Bell as a candidate in the local council elections in Wallsend; he was a lifelong socialist and a founder of the ILP (Independent Labour Party) in the area, so we put him up as a candidate. They were difficult times for a revolutionary party to be actually propagating their ideas but nevertheless we did get a good response to our campaign and in fact I think we gained many votes in that local council election in Wallsend, which wasn’t a very big ward; I think it was 340+ votes we actually got, because there was actually quite a sympathetic response to our ideas at the time.

From then on I was fully committed to the ideas of the Revolutionary Communist Party until I was 21. After I had finished serving my time, I was conscripted into the forces. I came out of my apprenticeship on the 26th of October and I was conscripted immediately and I was in the air force before Christmas. I had been forewarned that this would happen, when I was working at Reyrolle’s, by my foreman who took some delight in saying, “Landles, as soon as you’re finished your time, they’ll have you out of here lad!” and he was right; he knew something at the time which obviously I didn’t know.

Socialist Appeal: Just to come to an end, what would you say the lessons of the apprentices strike are for young revolutionaries and Marxists today?

BL: There will always be continuity as far as understanding of politics is concerned by young people. This is because their own experience is always in fact a shared experience with their family and they are aware of the objective conditions their families and the wider class face. Strikes hit the headlines and get into the newspapers and on television and the like, but in actual fact it is a continual battle in workshops, in all of the industries, and we see this now particularly in the civil service and with teachers out in struggle. It is a battle working people always face to try and achieve a reasonable standard of living.

Young people are brought up in that atmosphere so it’s not surprising that there is a continuity and that in almost all instances you’ll find young people involved in the class struggle. You’ll find young people taking part – taking part with a vigour and an energy which only youth itself can actually provide in these struggles. This will always be the case – that young people will respond immediately to any kind of struggle which is taking place at the time.