Read the full article in the Ted Grant Archive.

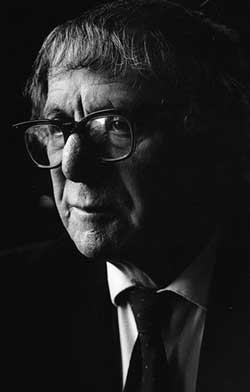

We republish one of Ted Grant’s most important

writings, from 1949. In the years after the Second World War the Trotskyist movement had to

reorient itself to a very different situation to that envisaged by Trotsky when

he had founded the Fourth International in 1938. Rather than falling into

crisis, capitalism in Western Europe and North America was experiencing a boom

which was later described as a ‘golden age’. After the post-War revolutionary

wave was seen off in the advanced capitalist countries, this made conditions

for revolutionaries very difficult. Illusions that capitalism had solved all

its problems began to develop quite widely. Ted analysed the causes of the boom

and why it would come to an end in ‘Will there be a slump? ’ in 1960.’

|

| Ted Grant in 1991 |

Developments in Eastern Europe and elsewhere were

equally puzzling. So far from Stalinism being thrown into crisis, it enjoyed an

enormous geographical extension into Eastern Europe and a new lease of life. By

this time the British Trotskyists had discussed the nature of these regimes

and, after a discussion as to whether they were state capitalist, recognised

that they were proletarian Bonapartist regimes identical to Stalinist Russia. (See Against the Theory of State Capitalism – Reply to Comrade Cliff by Ted Grant, 1949)

David James accepted this characterisation, but

further surprises were thrown up by the victory of the Chinese Revolution under

Mao, and the split between Stalin and Tito. Some Trotskyists were so impressed

by Tito’s declaration of independence from Stalin that they volunteered for work

brigades in Yugoslavia. It was left to Ted Grant to analyse the split as a

clash of bureaucracies and apply Marxist analysis to these new developments.

The pamphlet remains a masterly Marxist work of permanent value.

Below we reprint the

introduction published in ‘The Unbroken Thread ’, a selection of Ted’s writings.

(This is still available from Wellred Books for £6.95) This introduction is by

John Pickard.

“This Reply to David James…deals once again with the

Tito-Stalin split… ‘The only difference between the regimes of Stalin and

Tito’, it says, ‘is that the latter is still in its early stages. There is a

remarkable similarity in the first upsurge of enthusiasm in Russia, when the

bureaucracy introduced the first Five Year Plan, and the enthusiasm in

Yugoslavia today.’

Using the method of Marxism to describe the regime of Tito,

and hence explain the split with Stalin, the document takes the argument

further and extends it to the example of China. It elaborates further the

process by which Mao Tse Tung established his regime, explaining that it was,

of necessity, ‘deformed’ from the very beginning: ‘Basing itself upon the

peasantry, it (the Chinese Stalinist leadership) enters the towns not with the

aim and outlook of a genuine Communist Party, but with the aim of establishing

its power by manoeuvring between the classes. It does so not by transferring

its social basis to the proletariat – not as the direct representative of the

proletariat as would a Bolshevik party – but in a Bonapartist manner.’

Just as Tito has been able to assert his independence of

Moscow – because he came to power largely through ‘his own’ Yugoslavian

movement – so, therefore, Mao Tse Tung would also be able to assert his

independence, by resting on the Peoples’ Liberation Army and a nation of 500

million…’the danger of a new and really formidable Tito in China is a factor

which is causing anxiety in Moscow’.

By the late 1950s, the predicted differences between

Chinese and Russian Stalinism had begun to appear. Exchanges between the

Russian leader Nikita Kruschev and Mao Tse Tung became increasingly bitter

until, in mid 1960, there was a complete rupture, with the Soviet Union

withdrawing all the scientists and technicians previously placed in China to

aid its development. The public divisions between the Moscow and Peking

bureaucracies had a profound effect on the Communist Parties throughout the

capitalist world, with almost all of them suffering some split to form ‘Maoist’

parties.

As they had done previously with Tito, a section of the

remnant of the ‘Fourth International’, now composed of small ultra-left sects,

put Mao on a pedestal and hailed him as some sort of ‘unconscious Trotskyist’.

Encouraging the formation of Maoist Parties, one ‘Trotskyist’ sect even managed

the brilliant feat of losing its members to the organisation, the first time in

history that a ‘Trotskyist’ group participated in creating a Stalinist Party.”