A reply to ‘Comrade Clifford’ is an under-rated pamphlet by Ted Grant, partly because it has been fairly inaccessible for much of the time since it was written in 1966. Another reason it may be under-appreciated is because Brendan Clifford and his little sect have long since disappeared from the political scene. But, as usual with Ted, the arguments of this Stalinist and Maoist are just the basis for a wide-ranging Marxist survey of the entire history of Stalinism and the resistance to it nationally and internationally from 1917 to the Second World War and beyond.

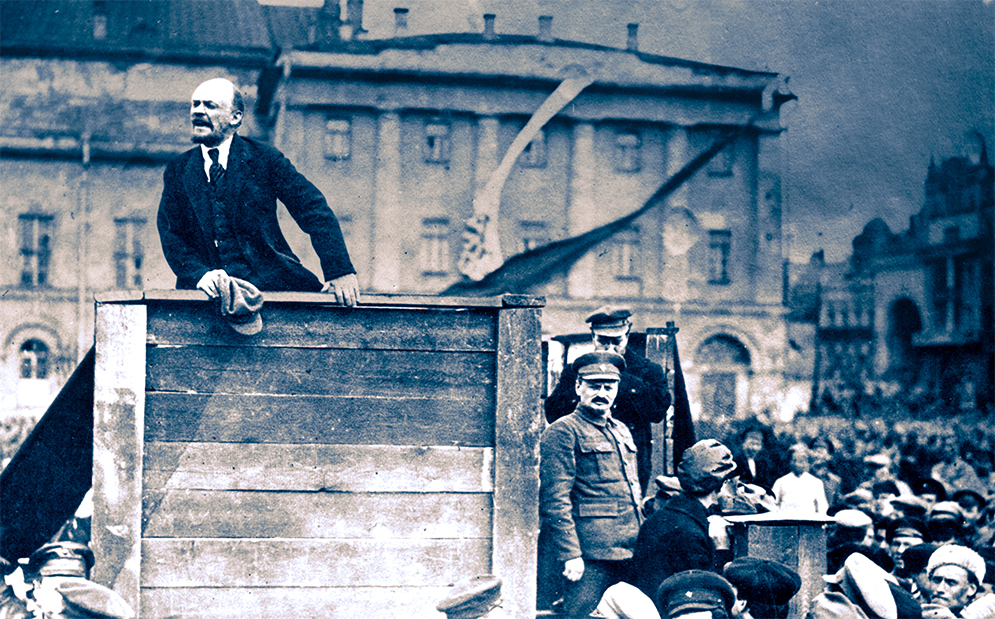

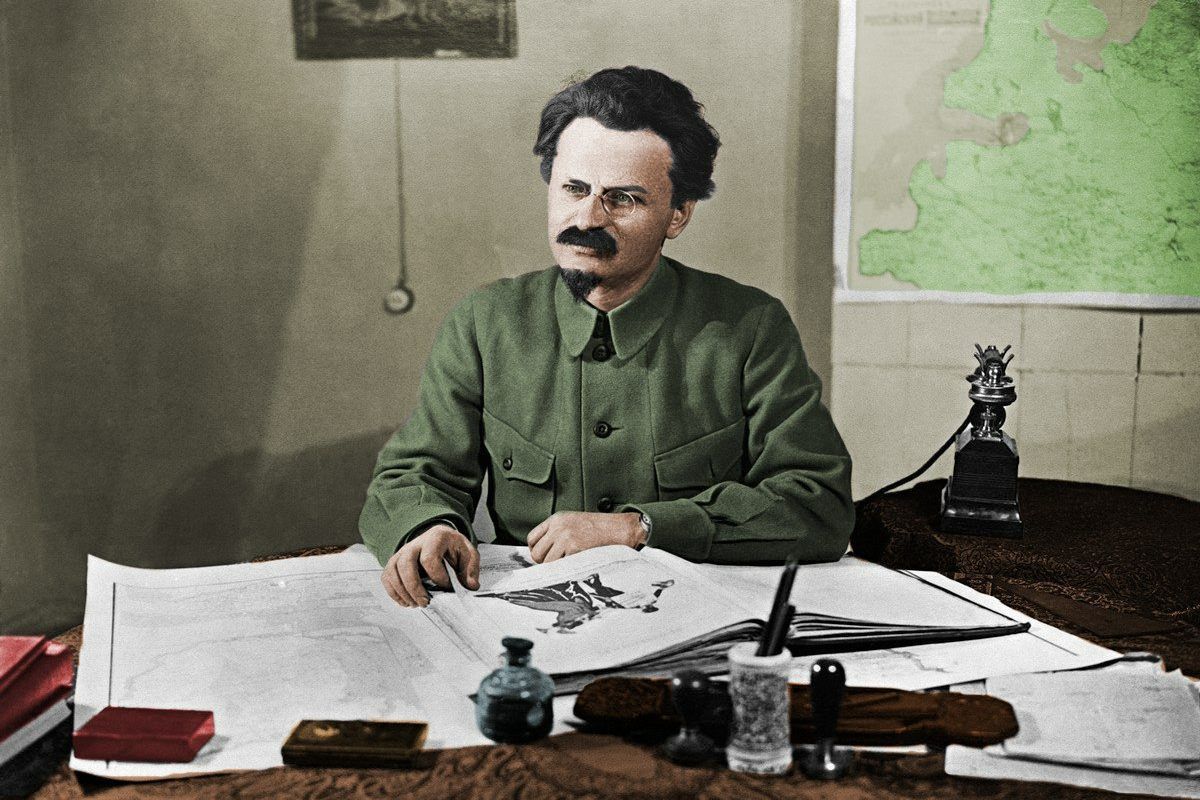

The debate enlightens two key theoretical concepts – the dictatorship of the proletariat and the theory of permanent revolution. Ted Grant unpicks the Stalinist lies which justified bureaucratic rule as ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat.’ He gives an inspiring yet realistic picture of the early years of the Russian Revolution, from workers’ democracy to Stalinist counter-revolution. As Ted shows the initial difference on which Trotsky and the Left Opposition took their stand against Stalinism was on workers’ democracy. In this they were defending the genuine heritage of Lenin.

Below we publish the introduction to the pamphlet from the selection of Ted’s writings called ‘The unbroken thread’. This introduction was written by John Pickard. The book is available from Wellred Books at £6.95

"(This) is a document, dictated in 1966, in defence of the basic tenets of Trotskyism. It was a reply to an Irish socialist, Brendan Clifford, who put the classic Stalinist position, using garbled and one-sided quotations from Lenin to show how Trotskyism was a ‘counter-revolutionary trend’ opposed to the ideas and methods of ‘Leninism’.

"Clifford circulated his views inside a small left wing group, the Irish Communist Group. His document was of more than historical interest because the position he adopted was an attempt to justify a Stalinist ‘stages’ theory of social revolution in Ireland. That would mean that the first task for the labour movement would be to participate – with middle class groups and the ‘nationalist’ elements within the capitalist class – in a struggle for the unification of Ireland, with socialism relegated to some distant future.

"The position adopted by the Trotskyists was that there was no barrier between the struggle to unify Ireland and the fight to transform society, that they were indissolubly linked. The unification of Ireland on a capitalist basis was ruled out, and conversely, the socialist transformation of society would be the basis upon which the unification of Ireland would become a reality.

"But the starting point of the Trotskyist position on Ireland was a defence of the general theories of Trotsky and T’rotskyism. The reply to Clifford, therefore, was a broad statement, outlining the early, pre-revolutionary differences between Lenin and Trotsky, and showing how their theoretical concepts compared to the living experience of the October revolution. Trotsky’s formulations proved more precise than Lenin’s ‘algebraic’ formula, but in reality both were vindicated by events: arriving at exactly the same position in 1917 after having travelled different paths. After the Revolution, both Bolshevik leaders considered their previous differences to be redundant and they were only dredged up after Lenin’s death, by the Stalinists eager to peddle the myth of ‘Trotskyism’.

"The reply also described the rise of the Stalinist bureaucracy in Russia and drew a sharp contrast between the ‘four conditions’ for workers’ democracy laid down by Lenin and the real situation as it became in the Stalinist USSR. As a matter of interest, some of the comments made about the attempts by the Russian bureaucracy to introduce reforms in the 1960s have a very modern ring to them. Like Gorbachev twenty years afterwards, Nikita Kruschev tried to move the sluggish Soviet economy forward by giving ‘incentives’ to managers and by ‘de-centralisation’ of economic planning – to little effect in the long run."

Read the full document in the Ted Grant archive.