Sci-fi franchise Star Trek is back on TV screens with the new CBS series ‘Picard’. The show’s bleak vision of the future is a far cry from the confident optimism of earlier incarnations. This reflects today’s impasse of the system.

When Star Trek left the small screen in 2005, fans must have wondered whether it was the end for their beloved show. Then in 2009, along came J. J. Abrams, rebooting it into a series of flashy Star Wars-style action films.

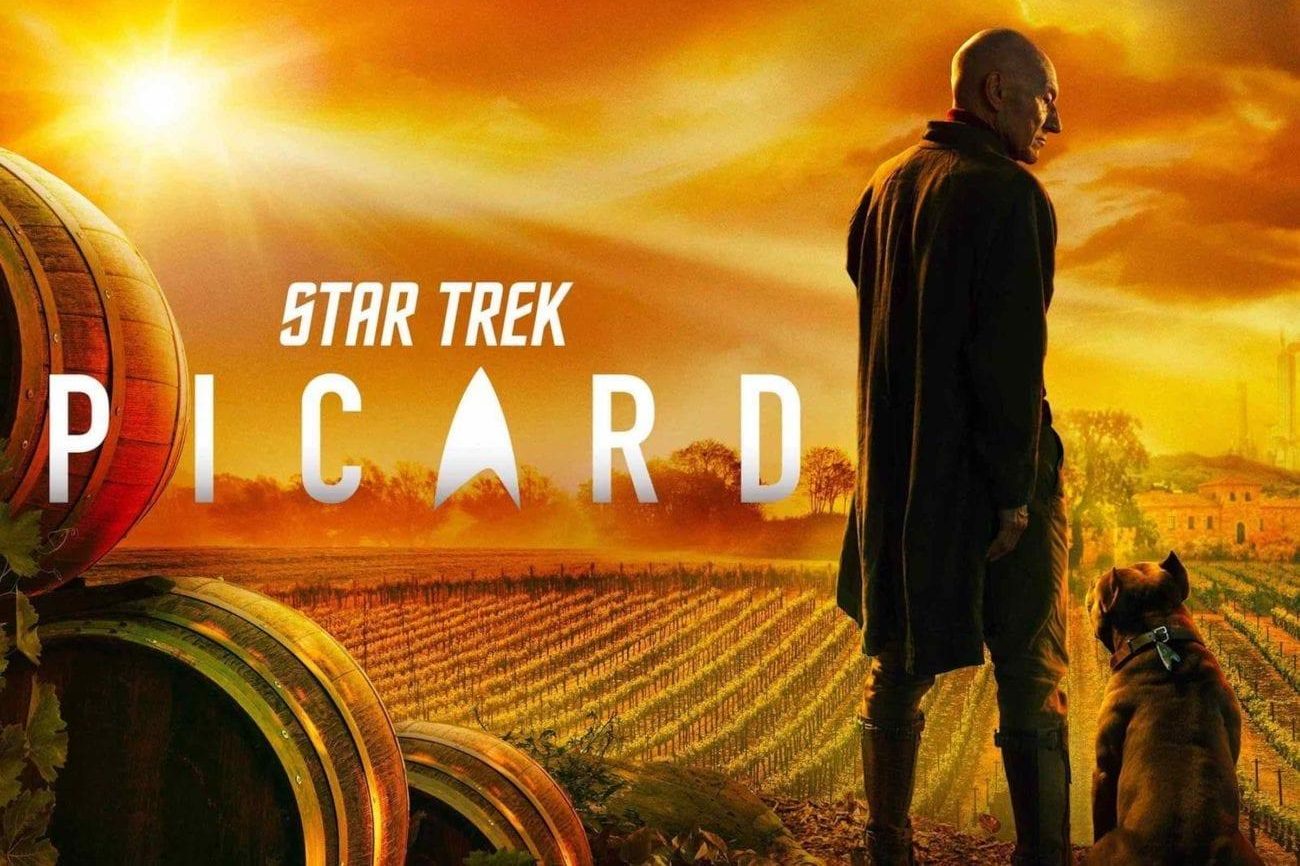

Whilst they bore little resemblance to the material that had come before, these films nonetheless re-ignited public interest. And so in 2017, CBS All Access brought Star Trek back to the small screen with their launch of Discovery. The first two seasons of the darker and more action-oriented show divided fans. But they proved successful enough to spawn a number of spin-offs, including the much-anticipated Star Trek: Picard.

Notably, the societies and worlds portrayed in these different series mirror the state of our own society over the decades, reflecting the alternating moods of utopian optimism and dystopian pessimism that follow capitalism’s booms, slumps, and stagnation.

What, in this respect, does the latest reincarnation of the Star Trek universe, Picard, tell us about the mood in today’s society?

Infinite diversity, in infinite combination

In 1964, TV producer and former World War II fighter pilot Gene Roddenberry pitched a ‘Wagon Train to the Stars’, depicting the intrepid crew of a starship, hurtling through space, visiting distant planets and encountering exotic alien species.

In 1964, TV producer and former World War II fighter pilot Gene Roddenberry pitched a ‘Wagon Train to the Stars’, depicting the intrepid crew of a starship, hurtling through space, visiting distant planets and encountering exotic alien species.

Whilst the show certainly had antecedents, Star Trek was something new. To begin with, the crew of the USS Enterprise featured members from different nations and ethnicities. The show’s emphasis on ethnic diversity reflected the struggles over civil rights at the time, and its fans even included Martin Luther King.

Not only that, at the height of the Cold War, Roddenberry skillfully used the science fiction setting to comment on contemporary politics in a way that would never have been tolerated in another kind of show. “[By creating] a new world with new rules, I could make statements about sex, religion, Vietnam, politics, and intercontinental missiles,” Roddenberry later explained.

Whilst Roddenberry was forced to make some compromises with the network, the crew of the Enterprise strove mostly to out-think rather than out-fight their opponents, seeking peaceful solutions wherever possible and presenting the scientists and engineers as the real heroes of the show. Earth was at the centre of a peaceful United Federation of Planets, where racism, bigotry and poverty were largely a thing of the past and cooperation was emphasised over competition.

A utopian vision

Whilst the 1960s television landscape placed certain limitations on Roddenberry, by the time he was planning his follow-up series in the 1980s, he felt confident enough to attempt something even more radical.

In the original series, Roddenberry was by his own admission deliberately ambiguous about the type of economic system present in the Federation. However, Star Trek: The Next Generation, set 80 years later, depicted a moneyless society, where humans had evolved past the accumulation of wealth and possessions, and instead concentrated on higher pursuits such as exploration, science and the arts.

French-American economist Manu Saadia discusses how such a society might work in his book Trekonomics. For him, the basis of the Federation’s utopia is twofold: all basic human material needs are catered for, eliminating poverty, inequality, and the need for some people to work for others merely to subsist; and drudgery has been largely automated, leaving time to do other things. These two advances have been achieved through a near-limitless energy supply, and devices called replicators which can synthesise everything from food to building materials instantly.

However, Saadia does not believe that the existence of material superabundance and automation alone guarantees such a society – no ‘technological singularity’ has been reached. He noted, for instance, that:

“If we decide as a society to make more of these crucial things available to all as public goods, we’re probably going to be well on our way to improving the condition of everybody on Earth… This is not something that will be solved [alone] by more gizmos or more iPhones. This is something that has to be dealt with on a political level, and we have to face that.”

Saadia references the hyper-capitalistic Ferengi, who possess the same replicator technology, but have them owned by a small number of people who charge for their use.

Into darkness

Science fiction certainly has a utopian tradition. The societies depicted in utopian fiction do not have to be perfect – the Federation has its fair share of rogue admirals and high-handed bureaucrats – but they do represent a qualitative leap forward from what exists today.

Yet the more common literary device is that of the dystopia, taking today’s society, exaggerating its (real or perceived) ills and transporting them to a nightmarish future. Instead of showing what a better future might look like, dystopian fiction warns us how things might turn out if present trends continue.

Popular series such as Babylon 5, Firefly and The Expanse all depict futures nobody would want to live in, with the common trope of small bands of honourable people struggling against an indifferent universe. Phillip K. Dick’s novels are even grimmer, frequently featuring no characters that could be seen in a positive light.

The first Star Trek series to be produced entirely after Roddenberry’s death was Deep Space Nine. Set on a space station far from Federation space, the show started by examining some of the murkier compromises the Federation was forced to make to ensure peace. It then delved into even darker territory with the Dominion War arc, which put the Federation and its allies up against a superior enemy that threatened to destroy them. The utopian ideals of the Federation were stretched to breaking-point as it fought for its survival.

Following on from this, we got J.J. Abrams’ blockbuster treatment of the franchise. Whilst Abrams’ reimagining of the original series won widespread praise, the film felt much more like Star Wars – another franchise Abrams would also eventually take the reigns of. Abrams did paint the Federation in a largely positive light, but the core Trek values of diplomacy, cooperation and scientific endeavour were buried under an avalanche of fight scenes, action sequences and lens flare.

This was then followed by the prequel TV series, Discovery. Unlike the wiser and more mature humans we saw in earlier series, the crew of the Discovery come across as a collection of rather unpleasant, damaged people, including a violent security chief who described prisoners as animals and rude and arrogant chief engineer. The Federation itself was little more than a military bureaucracy modelled on the present-day United States.

Return of the captain

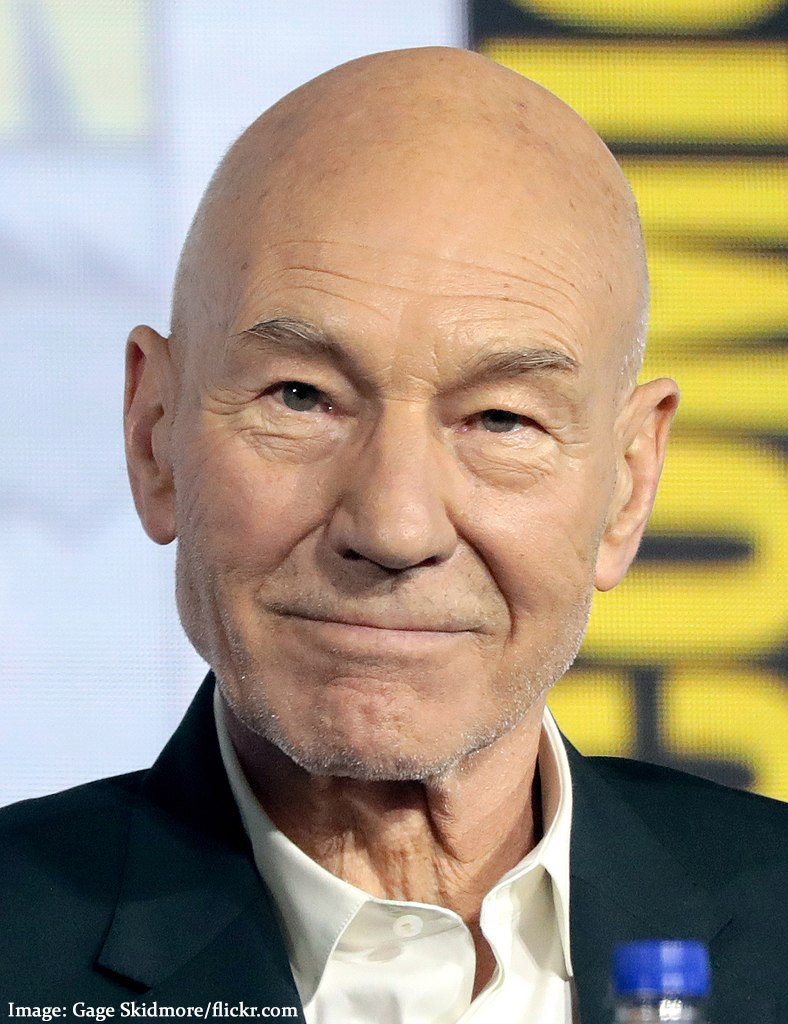

One of the most popular characters in the history of the franchise was The Next Generation’s Jean Luc Picard, played by Yorkshire-born Shakespearian actor Patrick Stewart. Quiet and thoughtful, yet assertive and passionate when the need arose, Picard embodied Roddenberry’s humanist ideal.

One of the most popular characters in the history of the franchise was The Next Generation’s Jean Luc Picard, played by Yorkshire-born Shakespearian actor Patrick Stewart. Quiet and thoughtful, yet assertive and passionate when the need arose, Picard embodied Roddenberry’s humanist ideal.

The actor is himself a long-standing supporter of the Labour Party and was drawn to the role partly because of Roddenberry’s utopian vision. When Stewart announced that CBS had persuaded him to make another show, the news was greeted with near-universal joy.

However, it soon became clear that Patrick Stewart had no interest in recreating that world. The actor clearly feels that in the present epoch, Roddenberry’s utopian optimism doesn’t make sense. As he explains in an interview with Variety:

“In a way, the world of ‘Next Generation’ had been too perfect and too protected… It was a safe world of respect and communication and care and, sometimes, fun. [The new show] was me responding to the world of Brexit and Trump and feeling, ‘Why hasn’t the Federation changed? Why hasn’t Starfleet changed?’ Maybe they’re not as reliable and trustworthy as we all thought.”

Set nearly 30 years after the events of The Next Generation, Picard depicts a Federation that has taken an isolationist turn in response to two major catastrophes, including the destruction of the Romulan homeworld. The whole tone and aesthetic of the series is much darker than Stewart’s previous series, with an embittered Picard estranged from Starfleet, and the camp-futuristic look of previous series replaced by something much more gritty and contemporary. What’s more, Federation citizens are shown working for money, and some have far more privileged lives than others.

With a compelling story and good production values, the series is gaining positive reviews from critics and fans alike. But it looks like Star Trek has well and truly moved away from its utopian roots into a much darker space.

Revolution and reaction

“People think the future means the end of history,” opines Captain Kirk in the film The Undiscovered Country, in reference to Francis Fukoyuma’s famous claim about the collapse of the Soviet Union. “Well, we haven’t run out of history just yet.”

“People think the future means the end of history,” opines Captain Kirk in the film The Undiscovered Country, in reference to Francis Fukoyuma’s famous claim about the collapse of the Soviet Union. “Well, we haven’t run out of history just yet.”

In fact, the decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the supposed triumph of liberal capitalism have been far from uneventful. Explaining Picard’s dark turn, Patrick Stewart cites Brexit and Trump as signs that the world has become a darker place. To him, the past two decades have brought nothing but chaos.

And indeed the past 20 years have included many catastrophic upheavals. For many left-leaning intellectuals and commentators, the forces of reaction are rampant everywhere. But this is to look only at half of the picture. The same period also encompassed the Arab Spring; the election of left governments across Latin America; big social and industrial movements across Europe; recent revolutionary developments in Sudan, Algeria, Lebanon, and Iraq; and even the popularity of socialist ideas in the United States, with the rise of the movement around Bernie Sanders.

Star Trek was originally somewhat vague about how its utopian Federation came into being. The film First Contact offered a vision of advanced aliens bringing enlightenment to a war-torn Earth. Yet the Deep Space Nine two-parter, Past Tense, offers something rather more interesting. In 2024, cities across the United States have vast camps for the unemployed, who are subjected to terrible conditions. These lead to an uprising in one camp, the ‘Bell riots’.

Whilst the episode takes a somewhat liberal turn – the riots apparently ‘turn public opinion’ and force the government to start dealing with the country’s social problems – the story nonetheless shows the role of the masses, and a mass movement, in challenging the status quo and bringing about change.

In other words, oppression, chaos and social upheaval can spark mass movements that lead to genuine revolutionary change. One of Deep Space Nine’s biggest contributions to the lore of the franchise was to depict social progress stemming not from some abstract enlightenment or gentle evolution, but from a struggle between living forces.

It is this side of the equation that often passes left-leaning intellectuals by: they see the problems in society, but are unable to conceive of something as chaotic and convulsive as a revolution offering a way forward.

That’s not to say that the role of the individual isn’t important. In Past Tense, Captain Sisko provides leadership that turns a potentially reactionary riot into a positive movement. In our real world, a fighting, revolutionary leadership can win people over to a radical, socialist programme – genuinely challenging the power of the capitalist class and ushering in the kind of society that Roddenberry dreamed of.

Star Trek inspired this author from a young age, showing the kind of world it is possible to build when the wealth of society isn’t hoarded by a parasitic billionaire class. Whilst the show’s contemporary writers may have lost faith that such a society can be built, this Marxist puts his faith in the working class across the globe. As Ferengi revolutionary Rom once said, echoing Marx’s famous call to arms in the Communist Manifesto, “Workers of the world unite – You have nothing to lose but your chains!”