Before the Second World War, Leon Trotsky put forward the perspective that the war would end either in the overthrow of the Stalinist bureaucracy of the Soviet Union through a political revolution, leading to the reassertion of workers’ democracy, or a capitalist counter-revolution that would destroy the USSR entirely.

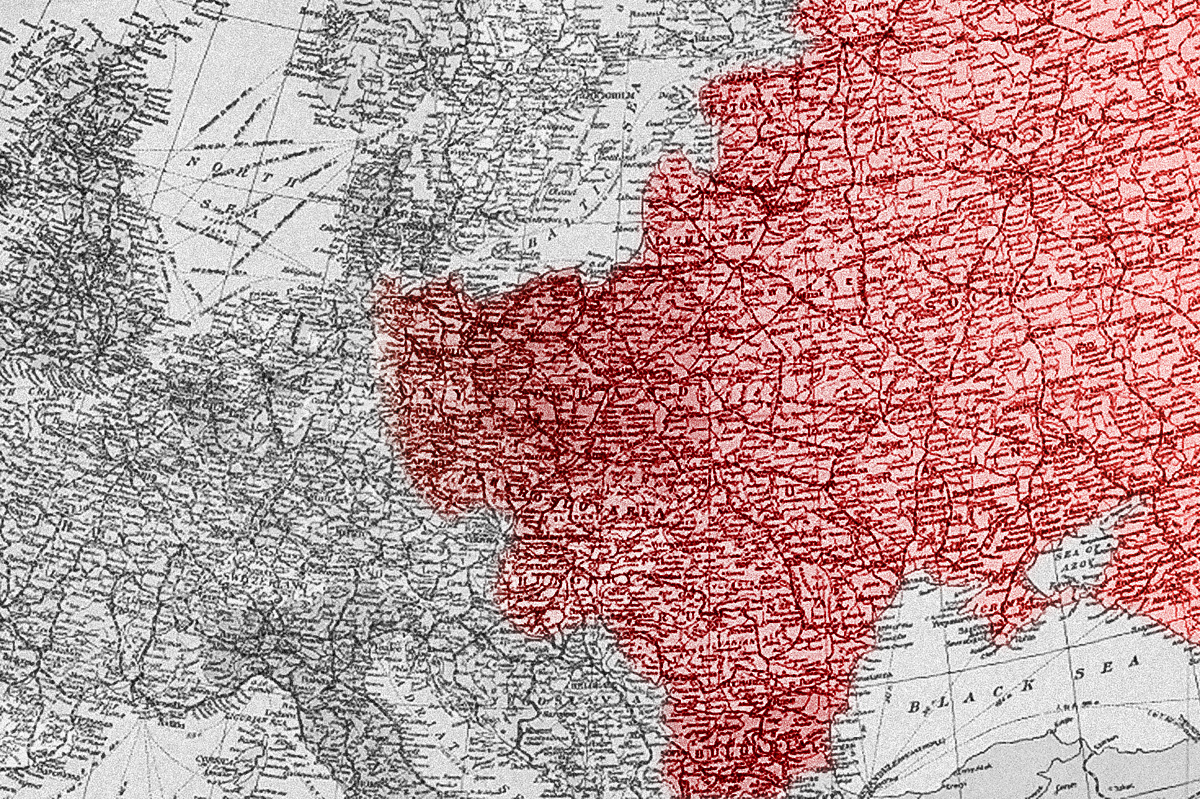

The end of the war, however, brought with it a drastically altered balance of world forces. The Red Army heroically defeated Hitler’s armies and flew the red flag over Berlin, holding a dominant position in Central and Eastern Europe.

Much of the national bourgeoisie of these countries – who had collaborated with the Nazi occupiers – had fled as soon as they saw the Red Army on the horizon.

Seeing the precarity of the situation, the USA attempted to bolster capitalism in Europe through tens of billions of dollars of Marshall Aid.

This backfired, however. Moscow forbade countries the USSR occupied from accepting this aid. Instead, they were compelled to expel the capitalists and essentially carry out ‘revolutions’, installing loyal ‘communist’ governments.

Instead of collapsing, therefore, Stalinism grew stronger. This demanded a reappraisal of perspectives from the Fourth International, which Trotsky established in 1938 to preserve the genuine traditions of revolutionary communism against the now thoroughly Stalinist Third International.

After Trotsky’s murder in 1940, however, the Fourth International had been left without its theoretical ballast, leading to all manner of illusions and confusion.

Theoretical failure

The first test was to determine the character of these new regimes in Eastern Europe.

Figures such as Tony Cliff argued that both the Soviet Union and its satellites were a form of ‘state capitalism’, with Stalin and the rest being a new ruling class. Others tried to make the case that the USSR remained a workers’ state, but the new regimes in Eastern Europe were state capitalist.

What was needed was a scientific study of the concrete developments in Eastern Europe. This required a return to the method of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky.

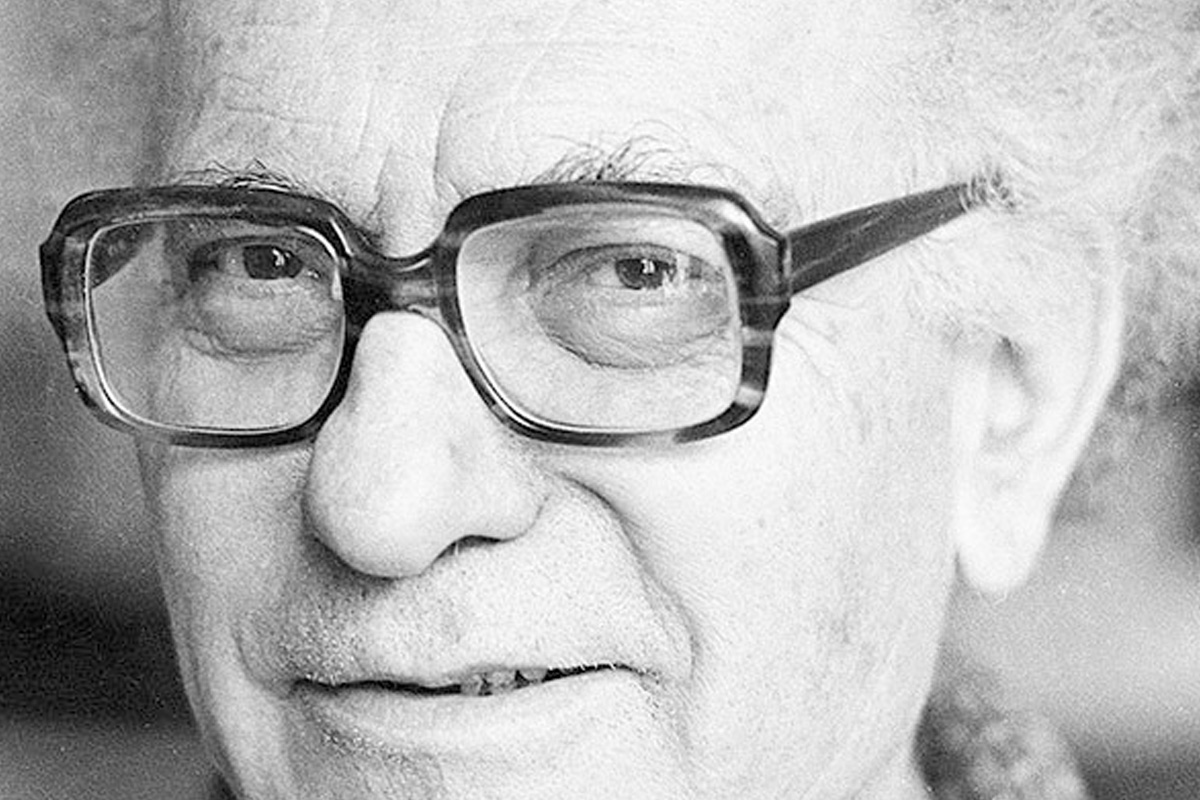

This task was taken up by Ted Grant, a leading figure in the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) in Britain.

Rather than basing his analysis on superficial symptoms, Grant attempted to determine the essential character of these regimes.

Firstly, what economic relations did the ruling bureaucracies defend?

Capitalism had now been abolished in Eastern Europe. Yet these new regimes started where the Soviet Union left off, with all traces of workers’ democracy extinguished.

The revolutions themselves were carried out in a bureaucratic manner, with the energetic masses jettisoned as soon as they had served their purpose.

Czechoslovakia in 1948, for example, saw armed demonstrations of workers and peasants on the streets demanding the establishment of a communist-dominated government, as opposed to a coalition with the capitalist parties.

‘Action committees’ were established, organising radical workers and students, and occupying offices and newspapers to seize power.

The intervention of the masses played a key role in booting out the capitalists, and ensuring a peaceful transition.

The workers and peasants gave their wholehearted support to the measures taken by the Stalinists, who – among other things – nationalised the commanding heights of the economy and instituted a monopoly on foreign trade.

The initiative of the masses had carried out this revolution. But the action committees were quickly sidelined, with a regime established in the model of Moscow.

Ted Grant concluded that these were a form of ‘proletarian Bonapartism’. The working class had been politically usurped by a bureaucratic caste, which rolled back many of the gains of the revolution. Capitalism, however, had been abolished. The basis of these regimes was a nationalised planned economy.

Grant described the setup as “a caricature of workers’ rule”.

“In a society where private ownership has been abolished and there is no democracy, the powers of the state gain enormous extension. The state raises itself above society and becomes a tool of the bureaucracy in its various forms: military, police, party, ‘trade union’ and managerial. These are the privileged strata within the society. They are the sole commanding stratum.” (The Colonial Revolution and the Sino-Soviet Dispute, Ted Grant)

Comparing this Bonapartism to its bourgeois counterpart, based on an analogy with the regime of Napoleon I, Grant continues:

“Just as bourgeois Bonapartism, manoeuvring between the classes, nevertheless in the last analysis, defends the basis of capitalist society, so in the same way proletarian Bonapartism rests in the last analysis on the base created by the revolution: the nationalised economy.” (ibid.)

The emperor has no clothes

The inability of the Fourth International leaders to understand new phenomena thrown up after the war was fundamentally down to their political weakness. In the face of a complex world situation, they lost their heads.

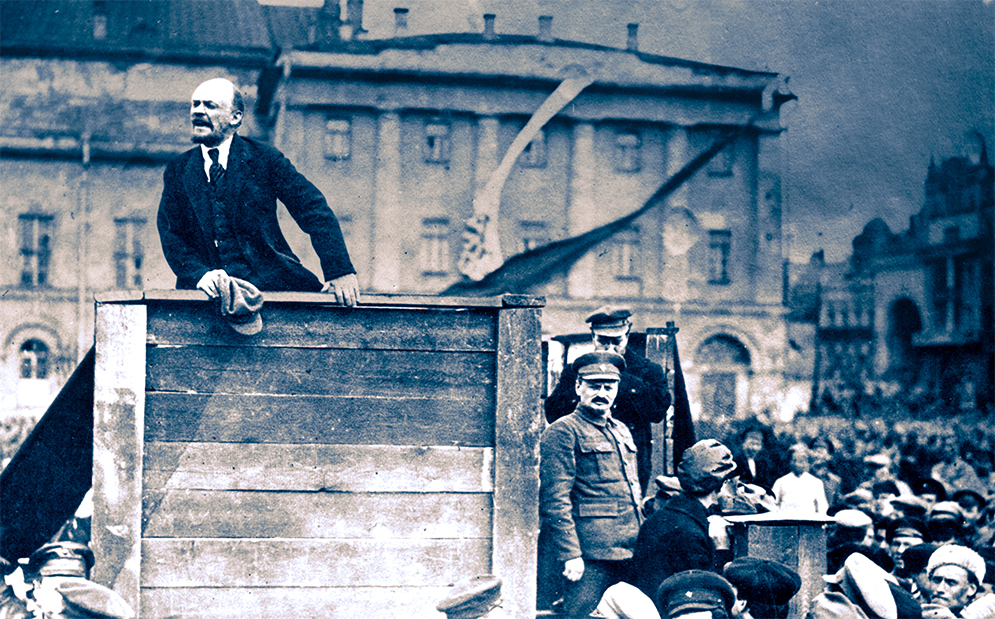

During the debates around the question of the Soviet Union in the late 1930s, Trotsky brought things back to the fundamentals.

In a masterful article called The ABC of the Materialist Dialectic, he explained the necessity of a correct method, and the dangers of ignoring it:

“It is not surprising that the theoreticians of the opposition who reject dialectic thought capitulate lamentably before the contradictory nature of the USSR. However the contradiction between the social basis laid down by the revolution, and the character of the caste which arose out of the degeneration of the revolution is not only an irrefutable historical fact but also a motor force. In our struggle for the overthrow of the bureaucracy we base ourselves on this contradiction.”

Once Trotsky had been murdered, the remaining leaders proved incapable of thinking in the dialectical way Trotsky explained. Instead, they took a superficial and formalistic approach. They made surface-level observations about Soviet society: the state was repressive; the bureaucracy was enriching itself off the planned economy; and so on.

Exacerbating their poor method was the weight of bourgeois public opinion – naturally opposed to the USSR. This pushed petty-bourgeois layers into theoretical justifications for their political weaknesses.

It was Grant who kept the flame of genuine Marxism burning. In the debate around state capitalism, he too brought things back to fundamentals.

Critiquing Cliff’s theory of state capitalism, for example, Grant took aim at Cliff’s method, pointing out that he attempted to mould the facts to fit his pre-conceived conclusions:

“Instead of applying the theoretical method of the Marxist teachers to Russian society in its process of motion and development, he has scoured the works to gather quotations and attempted to compress them into a theory.” (Against the Theory of State Capitalism, Ted Grant)

You can see this incorrect method in how the International treated Trotsky’s pre-war perspectives.

For Marxists, the ability to make predictions on the general line of march of events is incredibly important, allowing us to take a long view of processes.

Trotsky always stressed, however, that perspectives are conditional. They certainly aren’t a crystal ball. Yet this is exactly how the leaders of the Fourth behaved towards Trotsky’s analysis.

As Grant recalls in his (newly republished) History of British Trotskyism:

“One conference in 1946, when we raised the question of Trotsky’s prediction that in ten years not one stone upon another would be left of the Stalinist and Social Democratic organisations with one of the representatives of the SWP [American section of the International], he said: ‘Don’t worry, comrades! Trotsky wrote that in 1938. There are still two years to go.’”

In other words, they hopelessly clung to perspectives from almost a decade ago, and crudely foisted them upon a world that had decidedly developed in a different direction. This method has more in common with astrology than with Marxism.

‘Unconscious Trotskyism’

Even more confusion was thrown into the mix in 1948, when there was a split between Tito, the leader of Yugoslavia, and Stalin over the question of Yugoslavia’s independence against Soviet influence.

One contributing factor behind this split was Tito’s wish to create a federation of Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Albania – in which Yugoslavia would have played the dominant role. This would have weakened the influence of Stalin’s USSR, and was therefore something Moscow could not tolerate.

Like the rest, Tito’s regime had been characterised by the Fourth International as state capitalist. Consequently, these ‘theoreticians’ were blown off course by Tito’s denunciation of Stalin. Overnight they declared Yugoslavia to be a “relatively healthy workers’ state”, even going so far as to declare Tito to be an “unconscious Trotskyist”!

Such a feat of acrobatics was never theoretically explained to the ranks of the International. Indeed, there was no justification for this about-face.

They were operating on a completely empirical basis, blown around by events, lacking any understanding whatsoever of the reasons why things were happening.

These leaps from one position to another – absent of any explanation – only sowed confusion within the movement.

A question of method

The ranks of the RCP were not immune to such confusion. In his Reply to David James, Grant responded to claims of Tito’s alleged ‘unconscious’ Trotskyism from a member of the party’s Central Committee.

James argued that the split between Tito and Stalin had to be a clash between opposing class forces, for “when Trotsky spoke of the possibility of such an event, he was careful to describe the class lines on which it would break: he spoke of the ‘fraction of Butenko’ (bourgeois fascist) and the ‘fraction of Reiss’ (proletarian internationalist).”

Therefore, he argued, the task was now to determine whether or not Tito represented a bourgeois or a proletarian tendency.

Grant used this discussion as an opportunity to raise the political understanding of the ranks of the RCP, bringing it all back to the question of how to correctly apply the Marxist method.

He explained that James’ argument and its strict adherence to opposing class forces demonstrated a mechanical understanding of the state, which placed rigid categorisations above the real historical process.

To establish the class character of a state is important. However, this does not exhaust the question.

History has known all manner of states representing the same economic relations. For example, democratic republics, fascism, and bourgeois bonapartism all defend capitalist property relations.

To assume that all tendencies arising in the state must reflect opposing class interests is therefore a mistake, undoubtedly encouraged by the theoretical flip-flops of the International.

It is also true that Trotsky spoke of class divisions being expressed within the bureaucracy, and predicted that a crisis may bring these to the surface and lead to a major split. These divisions, however, never became as differentiated as predicted. James made the mistake of converting a conditional prognosis into gospel.

That around 50,000 of Stalin’s officials within the Yugoslav party were purged does not signify that Tito represented a different class to Stalin.

Tito possessed an independent base of support due to his role in the war: it wasn’t the Red Army that liberated Yugoslavia from Nazi occupation, but Tito’s partisans. This put him in a position of power compared to the grey-faced Moscow stooges that had been parachuted into power in other Eastern European countries.

The balance of forces therefore favoured Tito, allowing him to beat back Stalin’s interference.

The decisive question

The RCP offered critical support to Yugoslavia at the time, as a federation with Bulgaria and Albania would have given them more freedom from Moscow’s domination. They therefore put forward the slogan:

“For an Independent Socialist Soviet Yugoslavia within an independent Socialist Soviet Balkans. This can only be a part of the struggle for the overthrow of the capitalist governments in Europe and the installation of workers’ democracy in Russia.” (Behind the Tito-Stalin Clash, Ted Grant)

At the same time, the RCP was careful not to sow any allusions in Tito’s regime or his intentions. This was merely one Stalinist bureaucracy manoeuvring against another.

In Britain, the ‘official’ Communist Party – firmly in the pocket of the Stalinist regime – parroted the Moscow line, accusing Tito of using methods “borrowed from the arsenal of counter-revolutionary Trotskyism” (Daily Worker, 30 June 1948).

Ironically, both the Fourth International and the Stalinists were in agreement on Tito’s alleged ‘Trotskyism’.

Applying the Marxist method does not mean simply putting a minus wherever our enemies put a plus, or rigidly categorising the world into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ camps. It requires a sober and scientific assessment of the situation, starting with the living process of events.

As the leaders of the Fourth International demonstrated so readily, a failure to grasp the Marxist method makes it impossible to understand contradictory phenomena such as Stalinism, which is characterised by empirical zig-zags based on the bureaucracy’s immediate interests.

“It was not only a question of what was done, but who was doing it, how it was done, in whose interests and for what reasons,” Grant wrote, discussing Tito’s purge of Stalinists, warning of the dangers of taking events at face value. “That was the decisive question!”

Conscious Stalinism

On this basis, Ted Grant was able to point out that Tito was less of an ‘unconscious Trotskyist’ and more of a conscious Stalinist. The Soviet bureaucracy had emerged slowly, and found its feet empirically, whereas Tito consciously applied the lessons of his Russian neighbour, and so was sure to purge Stalin’s men before he met the same fate.

The destruction of capitalism; the expansion of the planned economy; the fiery speeches against Stalin: none of this was carried out to meet the needs of socialism or in the interests of the working class, but in the interest of the bureaucracy.

Similarly, Stalin’s expulsion of the bourgeoisie from Eastern Europe and the establishment of these planned economies was not down to a commitment to international revolution. The bureaucracy ultimately didn’t want to share its control of the state – the source of its prestige and privileges – with the capitalists.

Furthermore, as mentioned, the bourgeoisie had largely fled at the sight of the Red Army. The Soviets were therefore compelled to fill this vacuum themselves.

Trotsky described this in 1939 when writing about Stalin’s invasion of Eastern Poland. He used the analogy of Napoleon I following the French Revolution:

“The first Bonaparte halted the revolution by means of a military dictatorship. However, when the French troops invaded Poland, Napoleon signed a decree: ‘serfdom is abolished’. This measure was dictated not by Napoleon’s sympathies for the peasants, nor by democratic principles, but rather by the fact that the Bonapartist dictatorship based itself not on feudal, but on bourgeois property relations.” (The USSR in the War, Leon Trotsky)

In 1929, for example, Stalin reversed his previous policy of supporting the kulaks – the wealthy peasants – in their efforts to ‘get rich’, and now called for their liquidation as a class. In doing so, he adopted vast swathes of the programme of Trotsky’s Left Opposition, albeit in a crude and caricatured manner.

This was largely focused on rapid industrialisation through five-year plans. Some layers of the Opposition interpreted this as Stalin realising the error of his ways and correcting course.

Far from it! The change in course was based on the empirical needs of the bureaucracy. They had empowered the right wing in order to crush Trotsky’s Left Opposition. In doing so, they conjured up forces that were vying for a restoration of capitalism, which – if successful – would have ended Stalin’s regime. Having crushed the left, they could now turn on the right.

These measures weren’t a means of developing socialism, but a means of securing the position of the bureaucracy, which made no steps towards workers’ democracy whatsoever, and would carry out many more zig-zags when its immediate interests changed.

Tito himself would go through a similar process in the late 1960s. In the face of economic crisis, he implemented a series of reforms promising greater decentralisation and democratisation, with a purge of many old bureaucrats thrown in for good measure.

“Tito, like Stalin before him is shifting the blame onto one set of bureaucrats while leaning on another,” Grant explained in a 1966 issue of Militant. “The basic system remains the same.”

For a Marxist, it is not sufficient to take things as they are in the moment. We must study things as a process, to understand in which direction things are developing. In this case, the question was: were Tito’s moves a step towards international revolution and socialism, or a step towards a consolidation of the bureaucratic caste?

Thus, despite the musings of the ‘theoreticians’ of the Fourth International, none of these regimes achieved socialism. Instead, they were driven into stagnation and eventual collapse, and these same bureaucrats became the capitalist oligarchs of today.

Tell the truth

Rather than admitting to their mistakes, and using political discussion to raise the political level of the organisation – as Grant did with the RCP – the leadership of the Fourth International put their personal prestige first.

Unable to hold their own in any fair debate, the leadership opted for organisational manoeuvres to enforce their line and silence dissent.

This has nothing in common with the traditions of Bolshevism, but is closer to the methods of Stalinism.

These setbacks never got to Grant, who dusted himself off and got back to the task at hand – namely, building a revolutionary organisation of communists who can actively apply the method of Marxism, rather than repeating lifeless slogans devoid of content.

This is the heritage of the RCP that we defend, and are building upon today.