The resounding victory for Pablo Iglesias and his list of candidates at the recent Podemos congress, the National Citizens’ Assembly, marks an important development for millions of workers and youth in Spain. At the same time, it represents a defeat for the ruling class, who hid behind the right-wing stance of Íñigo Errejón.

The resounding victory for Pablo Iglesias and his list of candidates at the Podemos congress, the National Citizens’ Assembly, marks an important development for millions of workers and youth in Spain and, by extension, for the Spanish and European left. At the same time, it represents a defeat for the ruling class and the forces of reaction, who hid behind the right-wing stance of Íñigo Errejón, with the desire of dealing a demoralising blow against everything that is dynamic and truly progressive in Spanish society.

Pablo Iglesias won 51% of the votes for his list and about 55% for his three documents – the political, the ethical and the organisational. If we add the 13% and 10% and 11% achieved by the Anti-Capitalist current for their slate and their documents, respectively, that gives an overall support for the left of the party of 65% compared to 34% achieved by the right wing represented by the “errejonista” current.

The Podemos which emerges from this victory is one that bases itself on the aspirations of working class families and militant youth for a future of dignity and social justice, and which aims to use political institutions as a platform to denounce the false character of bourgeois democracy and to use parliamentary and council activity to mobilise the masses. This is the only way to advance the political consciousness of millions of the exploited and oppressed; the only way to wrestle from passivity and uncertainty the broad and politically more backward layers that need to go through more experiences.

The stance of Errejón’s wing was diametrically the opposite. They want to base the party on the petty bourgeoisie and the more backward layers of the population, and avoid pushing these layers towards the idea of social transformation; to take backwards the political consciousness reached by the millions who have already turned their backs on the old regime, promoting the prejudices and reactionary ideas of the most conservative layers of the population, and leading the party to increasingly mimic the ideological positions of the PSOE and Ciudadanos [Citizens], thus leading it into decline. It has been precisely this policy of playing ostrich, eliminating any hint of radicalism in the past two years – a policy of half measures and half-truths elaborated by the previously dominant errejonista faction – which led Podemos and Unidos Podemos [Podemos’ alliance with United Left and other forces] to electoral stagnation on June 26 last year.

Although we do not share all the political analysis and organisational proposals of the Pablo Iglesias wing, which we have already discussed in previous analyses (see below), we insist on what is the essential aspect for us – and that was what led us to give this wing critical support in this Congress. By leaning on the most dynamic sector of the working class and the youth, the Pablo Iglesias wing has left the door open to being influenced by this layer; to moving in line with the development of the class struggle towards sharper, clearer positions that challenge the capitalist system openly – that same capitalist system that only offers pain, suffering, poverty and barbarism everywhere.

The hysteria of the bourgeois media

In sharp contrast to the enthusiasm of most of the members of Podemos, the bourgeois media have not been able to hide their surprise at the overwhelming victory of the Iglesias’ wing. As with the Errejón wing, they thought Iglesias would win, but by a much smaller margin, with the Errejón wing coming a close second and leaving the followers of Iglesias without an absolute majority in the leadership, the National Citizens Council. They were hoping to be able to unleash a media campaign to highlight the decline of the Pablo Iglesias wing as a result of its “radicalism”, against which they hoped to oppose the moderation and statesmanlike nature of the Errejón wing, seeking to expand and instigate infighting so as to demoralise the activists, supporters and voters of Unidos Podemos. However, a very different reality has emerged from the Vistalegre congress.

As expected, all the front pages and analysis of the bourgeois media following Monday were full of mourning: “Podemos radicalizes”, “The beginning of the purge [of the Errejonistas]”, “hard line imposed.” A spokesman for the PSOE’s Interim Leadership, which manages the party in the interests of the ruling class, also chipped in. Speaking to the Onda Cero radio channel, Mario Jimenez said, “Pabloism-Leninism has won” and insisted, in case there was any doubt, that “the PSOE wants to address itself to the moderates so they can help us push forward a moderate project in Spain”.

The bourgeois media and its agents in the PSOE understand this internal debate inside Podemos the same as the Marxists: what was at stake was the taming (or not) of Podemos (and, by extension, that of Unidos Podemos) by the regime. Monday’s editorial in El País was forced to admit the bitter truth:

“That defeat is also an unmitigated defeat of the [party’s] current number two and parliamentary spokesman, Inigo Errejón, who has unsuccessfully tried to convince members of the need to moderate the approach of the party and position it stably within the institutions in order to gain credibility as a government force and to broaden the electoral base of support in upcoming elections.”

One of the most prominent hired pens of El País, Ruben Amon, put it more clearly in his analysis on Sunday. In addition to unleashing all his hatred and malevolence against Pablo Iglesias and the party ranks, he said:

“the spirit of United Left has taken hold of the essence, but it represents a huge electoral limit, the limits which Errejón aspired to overcome by normalizing institutional life and convincing his people that the future of Podemos, if any, is to the right of Podemos” [emphasis added].

The pre-congress discussion

Many people, including most of the activist base of Podemos, have struggled to get a clear idea of the character of the political differences at the top of the party, and to understand the level of tension reached in the debate between the Iglesias and Errejón wings. That has to do largely with the obtuse and convoluted structure and organisational methods of the party.

Podemos’ congress procedure, very democratic in appearance, poses enormous difficulties for genuine democratic participation of the ranks. The documents for discussion should have been available at least two months in advance and at the disposal of the members, so that they would have had enough time to read them and discuss them in the local branches and in wider gatherings. But they were only published three weeks before the Congress, making it impossible for tens of thousands of people to find the time to read and discuss hundreds of pages of documents of each of the currents. To make matters worse, the members were not allowed to submit amendments to these documents. In addition, hundreds of political and organisational contributions written by members and endorsed by the branches were barely publicised, and were finally published on the website of the organisation only a week before the voting, with the aggravating circumstance that the five most voted, which had the right to be presented and defended at the National Citizens’ Assembly were not binding on the organisation. These methods, defended by the three main currents, express their desire to control and steer the membership, and thus to prevent any voice which does not fit with their proposals from being heard. There is still a lot to do to make Podemos a fully democratic organisation, and this demand will be posed, sooner or later, by the thousands of members.

And yet, despite everything, the bulk of the membership could sense, perhaps not the fine details, but at least the broad strokes of what was at stake in this Citizens’ Assembly. The long experience of 40 years of bourgeois democracy in the country, with decades of betrayals by the leadership of the PSOE and the PCE [Communist Party] and IU [United Left], have not passed in vain. There was a feeling that Inigo Errejón and his wing wanted to shift Podemos to the right and push Pablo Iglesias into a corner. Iglesias is still seen by the bulk of the ranks as the most charismatic leader in Podemos and the one who best expresses their desire to transform society.

This feeling was reinforced by the clear bias and sympathy for Errejón expressed by the bourgeois media, the same media which demonises Podemos and its leaders, and which are viewed with deep suspicion and even contempt by millions of people.

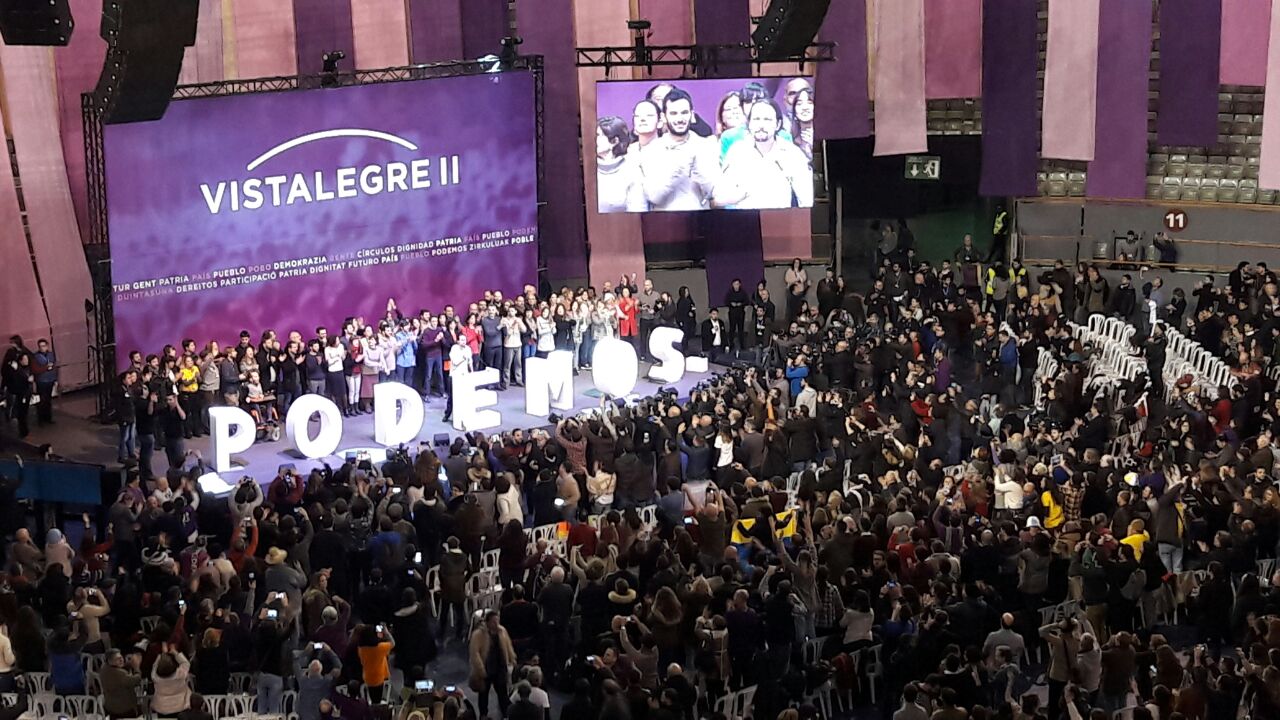

National Citizens’ Assembly

The crucial day of the Citizens’ Assembly in Vistalegre was Saturday 11 February. Thousands of activists and supporters thronged at the gates of the compound, in the hallways and in the stands. The atmosphere was sober, attentive and tense. After the arrival of the members of the outgoing National Citizens Council (the highest leading body of Podemos) applause and cheers started. But what broke the ice and put its stamp on the congress was when Pablo Iglesias took to the stage. He received a torrent of applause, with thousands of clenched fists following the rhythm of the shouts for “Unity, Unity”.

The thunderous cry for unity was a reflection of the limited level of pre-congress debate discussed earlier. In part, it is the logical conclusion of a highly mobilised honest layer of the rank and file that could not perceive thoroughly and clearly the political differences between the divisions that have opened up at the top, which are presented by the bourgeois media as just a personal clash. But the almost unanimous call for unity at Visatalegre was also the expression of a healthy sense of discipline, which was being demanded from the leadership in order to preserve the organisation against our enemies.

Beyond this, Pablo Iglesias and other speakers of his current were the only ones who stressed the political differences with the Errejón wing (though without naming him). The speeches of Errejón and his supporters, as well as those of the Anti-capitalists (Miguel Urbán and Teresa Rodriguez) in reality merely had the character of a rally. They criticized the political opponents of Podemos, but avoided any mention of the sharp political differences which have opened up inside the organization. Teresa Rodriguez (Anti-capitalists) made references to some programmatic measures proposed by her current (auditing the public debt, creating a public banking sector, defending “a new productive model”), but neither she nor Miguel Urbán raised any criticism of the right-wing ideas of Errejonismo. Their speeches were eloquent and combative, but would have gone down equally well in an election campaign, and thus helped to avoid debate in a congress plagued by political differences. Comrade Errejón, meanwhile, when the moment of truth came, in front of an audience of ordinary rank and file members, lacked the courage to openly defend the positions in his political document which had led him to the clash with Pablo Iglesias.

Anti-capitalists

We regret to say that the position of the Anti-capitalists current was particularly demagogic and disingenuous, taking into account that they regard themselves as the furthest left current in the organisation. They appeared as champions of unity, in order to win easy applause from the audience, and practically reduced the Iglesias-Errejón differences to a personal fight, hiding the politically pernicious character of the positions of Errejonismo.

Our position before the Assembly was that both currents, that of Pablo Iglesias and the Anti-capitalists, should have had a joint slate – as they did in the Madrid internal elections in Podemos three months earlier – against the common adversary of the right wing so as not to split the left vote. The Anti-capitalists could have maintained their political and organisational documents if they had wished. But they dismissed the attempt to have a joint slate with Pablo Iglesias because they thought they would get greater representation in the leadership of the organization by having a separate slate; on the eve of Vistalegre they said they were hoping to get between 4 and 8 seats in the National Citizens Council – in the end they only got two.

By refusing to fight Errejonismo head on in the pre-congress period, and even being complicit with it on organisational issues (they said they were closer to Errejón than Iglesias on these points), voting for this faction was seen as a lost vote by tens of thousands of activists who feared a victory of Errejón and the defeat of Pablo Iglesias. Hence, there was a closing of the ranks around Iglesias’ slate and documents to ensure the defeat of the Errejón’s wing. Thus, the Anti-capitalists paid a price for their opportunistic attitude.

The attitude of comrade Miguel Urbán after Vistalegre is to continue with this wrong position. Instead of celebrating the defeat of Errejonismo – which was determined to exclude any hint of leftism and anti-capitalism from Podemos had they won – he wants to appear as the champion of unity and defender of the presence of Errejón in the leadership of the organisation at the highest level of responsibility. It is a position that we do not support because it seeks to hide and mask the deep political differences that exist within Podemos and the class character that they express. We agree that all tendencies should have representation proportional to their support in the ranks at all levels of leadership in the organisation, but we also support the idea that the positions which have won majority support are those which should determine the policy of the organisation; and at the same that the positions defended by each current are expressed clearly, so that the membership has all the elements at its disposal to observe, monitor and follow the debates and political positions of each one of them.

Perspectives

After receiving a serious blow, the current of Inigo Errejón – which has its main base in the hundreds of public officials and full timers of the organisation, many of whom lack any links with the working class or social movements – is attempting to mask its defeat behind the defense of “plurality” in the leadership of the organisation. The bourgeois media is pushing in the same direction, warning against a “purge” that the new leadership is allegedly preparing against Errejón and the party apparatus on which it rests.

The current of Errejón has secured its presence in the National Citizens Council with 23 members, against 37 of Pablo Iglesias and two for the Anti-capitalists. It is logical and democratic that they should have proportional representation in the new party executive, which will be elected in the coming days. But it would be unacceptable that they should occupy any relevant responsibility that may be used to impede or block the new orientation of Podemos towards the working class and its presence on the streets, and towards the unity with the forces of the Left, nationally and regionally. And it is an elementary proposition that anyone can understand: Errejonismo must lose the disproportionate weight it has in the apparatus of the organisation, which does not correspond at all with its base of support. The new leadership must firmly ignore the thunderous cries about “purges” which the bourgeois media have launched. It must explain that it is a consequence of the democratic will of the party rank and file, emanating from the Vistalegre Assembly, and appeal to this rank and file when the ruling class counteroffensive resumes against the new leadership.

Sooner rather than later, Podemos will be met with the favorable winds of the radicalised mood in society. The overwhelming vote for Pablo Iglesias proves that there is no demoralisation or ebb amongst the most active and aware layer of the working class and the youth. The positions arising from Vistalegre are consistent with the developments that the class struggle in Spain will take in the coming months. The continuing casualisation of labour, low wages, long working hours; the feeling of impotence in the face of the abuses of the rich and powerful; rising prices; and the suffocating political environment imposed by the PP government, supported by the “triple alliance” of PP-PSOE-Citizens: all these are a recipe for a revival of the class struggle. In the coming months, the PSOE will emerge from its interim situation by ratifying = in the person of Susana Diaz – the umpteenth right shift in party policy, which will assure Unidos Podemos a much broader avenue for political agitation and popular support.

What is required is to advance in terms of the programme. The shameful increase in the price of electricity puts on the agenda the slogan of nationalisation of the utilities. But this abuse by those in power, and the growing social inequality that it entails, is consistent across all the companies that dominate the country’s economy. No significant progress can be made in public services, social services, job insecurity, unemployment, wages and social expenditure without breaking the stranglehold of the parasitic oligarchy at the top. Bank bailouts and scandals, with their multi-million scams, also pose the need to nationalise the banks as the only way of concentrating the country’s credit in a unified public banking sector, and to pool resources to fund a vast economic plan to solve the problems afflicting millions of working families.

Podemos emerges from Vistalegre much more mature and stronger, with a more aware membership ready to exercise accountability. What is required now is to go from words to deeds, to “have one foot in parliament and a thousand feet on the streets” – to be at the head of the struggle against the 1978 regime and the capitalist system as a whole.

Published on In Defence of Marxism

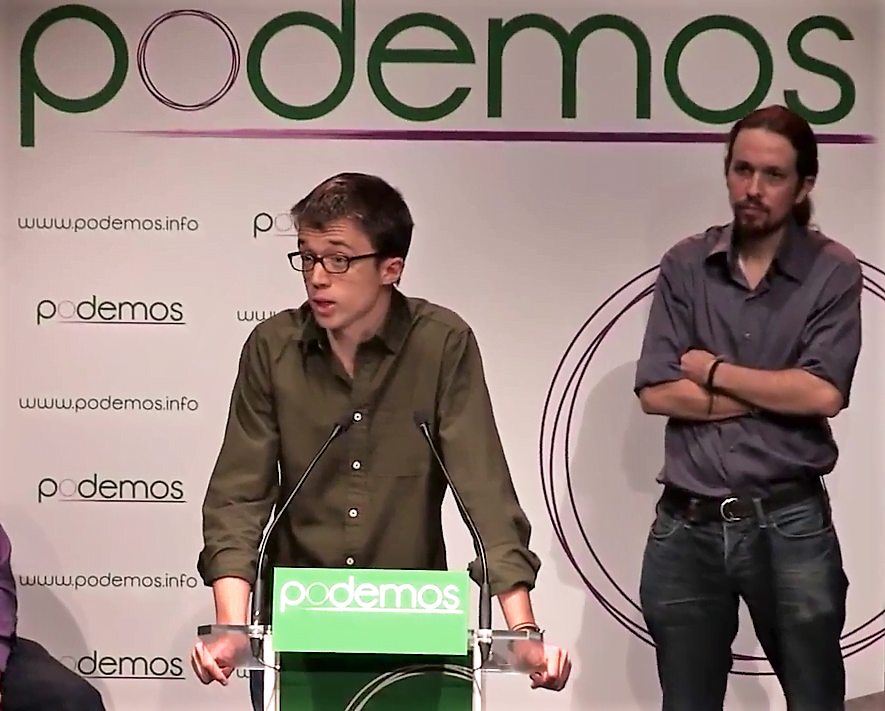

All pictures by Jose Camo, Lucha de Clases

The differences between Iglesias and Errejón: a reflection of the class struggle

By David Rey, Lucha de Clases

The fact that an open division about what strategy and tactics to pursue has emerged in the original leading nucleus of Podemos demonstrates that the political and organisational conclusions drawn from the founding Citizens Assembly (Vistalegre I) have proven to be false.

The fact that an open division about what strategy and tactics to pursue has emerged in the original leading nucleus of Podemos demonstrates that the political and organisational conclusions drawn from the founding Citizens Assembly (Vistalegre I) have proven to be false.

The thesis that the socio-economic crisis was merely a temporary phenomenon and that the task thus facing us was one of immediately winning the elections at any cost before the regime recomposes itself, led to a moderation of Podemos’s discourse and programme. Hence the vacillations and the zig-zags from left to right, which have left a large part of the membership (and actual and potential voters) disoriented.

In fact, when the language used by Podemos took on a more left-wing hue, the party was able to win positions and electoral support, as was the case in the general elections on the 20th December 2015 – only to lose it when they shifted to the right and took on a more moderate posture so as “not to frighten” the middle classes, as happened during the general elections of 26th June 2016 (“26J” as it is known in Spain).

With the argument of building an “electoral war machine”, a rigid apparatus with bureaucratic tendencies was created, which has been harassing comrades with more left-wing views. Political debate and decision making has remained concentrated in the hands of the organisation’s leadership, with local circles being emptied of political discussion and thousands of activists drifting away.

There were tactical errors prior to 26J, such as not having been able to convince a sufficient part of PSOE’s core voters that its leaders would prefer a PP government than ruling alongside Podemos-IU, as has now been proven to be the case. By failing to call a Podemos-IU led popular mobilisation demanding such a government, thus dispelling any doubts, the Socialist leadership were given the opportunity to present the proposal of a PSOE-PODEMOS-IU government as a mere manoeuvre, falsely blaming us for the continuation of the right-wing government. This in itself demonstrates – contrary to the opinion of comrade Errejón – that the left-right divide continues to be the main consideration in the political sympathies of working people, as they correctly see it as the line dividing rich and poor; bosses and workers; the restriction of democratic rights and their extension.

In the end, the need to expand electoral alliances to the left on a statewide level was recognised in the face of 26J, although in the case of IU this was done late and badly.

The thesis of comrade Errejón

The positions confronting one another – that of Iglesias and Errejón – express, in the last analysis, the pressures of the different social classes in society, as is the case in any profound and intense political debate.

Comrade Errejón is very clear to whom he is directing his message. In his document Recuperar la ilusión [Restoring Hope] he poses the need for an orientation towards the middle classes and calls for the moderation of both the image and language of Podemos, with “cross-cutting proposals, neither of the left nor of the right”. He treats the left with contempt, describing it as “folkloric and impotent” and presents a vulgar caricature of Marxism, without mentioning it by name, arguing that Podemos should be against “those who believe that positions in history are fixed by the economy.” He also makes clear his contempt for popular mobilisations: “Historically nothing frightens the people at the top less than the protests of noisy minorities”. And, this in the country of 15M and the Indignados! Where between 2012 and 2013 alone there were two general strikes and 130 daily protest actions, which created the very conditions for the emergence of Podemos!

According to comrade Errejón’s tendency we can find points of agreement that everyone can come together on: workers, the middle classes, the bosses, all for the purpose of “rewriting a social contract”.

His reasoning is simplicity itself. If we can succeed in pleasing all the social classes, if put forward the idea of uniting for the love of the fatherland and the nation, then we can all live happily in the happiest of all possible worlds. In this way everyone will vote for us: the poor and the rich, the businessmen, the workers and the youth; don’t you see that it really is that simple?

It’s no accident that comrade Errejón receives regular praise from the leaders of PSOE, the PP and the media of the regime. He himself complains about this. But are these not the very same right-wing leaders of the PSOE, the PP and Ciudadanos who also argue that leftism is out of date? Do they not argue, with the same ardour as comrade Errejón, in favour of “people’s unity” and of the fatherland? Let us be clear; there are no common interests between bosses and workers, between rich and poor, like the fatherland or the people. It only serves to hide the class interests and the domination and exploitation in society by big businessmen and bankers.

The ideas represented by Errejón’s tendency are nothing new. They are akin to those imposed by Felipe González in PSOE against the Marxist wing in the late 70’s in order “to win the middle classes”. If they succeed at Vistalegre II, they would lead Podemos to disaster, towards an ideological overlap with PSOE and Ciudadanos, and to the frustration of the expectations for a real change held by millions of workers, youths and of the exploited in our country. In addition, it would lead to an internal “state of emergency” being imposed against anything that smells of leftism, radicalism or socialism.

Vistalegre II

The pre-assembly debate has disgusted many militants. The documents of the main tendencies (Pablo Iglesias, Íñigo Errejón, Anticapitalistas) were only distributed to members three weeks prior to the Citizens Assembly itself. The circles are unable to amend them. Militants and circles are able to present their own contributions on political and organisational questions and vote on them, but such votes are non-binding!

Apart from everything else, the schedule of the debate has been confusing and information has arrived in an incomplete form to the circles. For this reason, only the most active nucleus of the organisation has had the opportunity to evaluate the content of the different proposals, contributions and documents in detail.

Now Iglesias and Errejón renege on the organisational model of Vistalegre I. This is not very credible in the case of Errejón. It was from amongst his supporters that the apparatus was organised through the ex-secretary of organisation Sergio Pascual – removed by Iglesias months ago – and which demonstrated a tremendous disdain for the rank and file. Although we share his criticism of granting special powers to the General Secretary (such as that of unilaterally calling referenda amongst the membership), it is not organisational questions which determine our support or lack thereof for this or that tendency but the political questions.

We have already explained our complete rejection of the positions and the list proposed by the camp of comrade Errejón, which represents the right wing of Podemos.

The other two currents (that of Iglesias and Anticapitalistas) better reflect the Podemos that the working class needs, maintaining their support for left-wing unity, and positioning the motor force of their politics in social mobilisation in opposition to the institutionalism of Errejón’s camp. Both, therefore, have our sympathy.

For an agreement of the “left” against the “right”

Fundamentally, from an ideological point of view, there do not appear to be substantial differences between Pablo Iglesias and Íñigo Errejón. Neither pose an alternative that goes beyond capitalism; both defend a narrow nationalism and their programs are limited to a series of progressive reforms.

Nevertheless, whilst Errejón and his followers have proven to be hyper-sensitive to the disciplinary whip of the ruling class, Iglesias’ camp, by resting on the most dynamic section of the working class and the youth, leave the door open to being influenced by them, to progressing along an evolution according to the development of the class struggle that could lead, down the line, to the formulation of socialist conclusions, although in an incomplete and insufficiently developed way.

The position of Anticapitalistas is further to the left, albeit with a high degree of ambiguity, as they do not argue openly for the adoption of socialist measures against big capital by a hypothetical, future Unidos Podemos government.

Nevertheless, the onslaught of the right-wing led by Errejón is very strong, and counts on the sympathy of the regime’s media. The presentation of two separate “left” lists could grant victory to the “right” and ensure its majority on the leadership.

For this reason we call for the unity of both wings. If the comrades of Anticapitalistas consider it impossible to amalgamate their political document with that of Iglesias, they have sufficient weight and means to make their proposals known to the rank and file via multiple channels. What this is about is ensuring the continuation of a Podemos oriented to the left and based on the working class and other excluded layers of the population; not of making a show of one’s weight in the party’s apparatus.

If such a unity is not forthcoming, we urge for a gathering of the vote around that wing with the greatest possibility of beating Errejón’s camp – that of comrade Pablo Iglesias – and for the future leadership body of the party to be based upon the unity between both left wing currents.