Spain: From Revolution to Counter-Revolution

Chapter 1: Why the Fascists Revolted

Chapter 2: The Bourgeois ‘Allies’ in the Peoples Front

Chapter 3: The Revolution of July 19

Chapter 4: Towards a Coalition with the Bourgeoisie

Chapter 5: The Politics of the Spanish Working Class

Chapter 6: The Programme of the Caballero Coalition Government

Chapter 7: The Programme of the Catalan Government

Chapter 8: Revival of the Bourgeois State: September 1936–April 1931

Chapter 9: The Counter-Revolution and the Masses

Chapter 10: The May Days: Barricades in Barcelona

Chapter 11: The Dismissal of Largo Caballero

Chapter 12: ‘El Gobierno de la Victoria’

Chapter 13: The Conquest of Catalonia

Chapter 14: The Conquest of Aragon

Chapter 15: The Military Struggle under Giral, and Caballero

Chapter 16: The Military Struggle under Negrin-Prieto

The Civil War in Spain

Chapter 1: The Birth of the Republic – 1931

Chapter 2: The Tasks of the Bourgeois-Democratic Revolution

Chapter 3: The Coalition Government and the Return of Reaction, 1931-1933

Chapter 4: The Fight Against Fascism: November 1933 to February 1936

Chapter 5: The People’s Front Government and its Supporters: February 20 to July 17, 1936

Chapter 6: The Masses Struggle Against Fascism Despite the People’s Front: Feb. 16 to July 16, 1936

Chapter 7: Counter-revolution and Dual Power

Foreword

The period in Spain between 1931 to 1937 was tumultuous to say the least. As Trotsky said, such was the heroism of the Spanish working class they could have made ten revolutions in those years.

With this in mind, there are many, many rich lessons to be learned from both defeats and victories, particularly in relation to the state.

After the King abdicated in 1930 and the left won the elections in 1931, the capitalists and big landowners had claimed to accept the Republic. However, in deeds they immediately began to undermine it using economic sabotage and funding fascist gangs.

The Republican-Socialist and Popular Front governments failed to take seriously this threat. They didn’t purge the state of pro-capitalist judges, police, civil servants, army generals and officers, etc. They didn’t expropriate the landowners and industrialists who had financed the counter-revolution.

Of course, as Ted Grant explains, this was because the government consisted of liberal politicians who, because of their class position, were unable to dismantle the capitalist state machinery, which defended and maintained their class interests.

At the same time, the liberals were also incapable of carrying out the basic tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution, predominantly agrarian reform. For instance, one million owners possessed 6m hectares, whilst 100,000 owners possessed 12m hectares.

The failure to carry out agrarian reforms led to growing discontent among the peasantry. The peasants, starved or half-starved and living in poverty, would soon turn to the counter-revolutionary forces, allowing them to resurge in the 1933 elections.

During ‘The Two Black Years’ that followed, the regime was successful in dismantling major gains of the revolution in a brutal wave of repression that saw tens of thousands imprisoned and tortured, wages slashed, etc. Ted Grant quotes one article which says that the regime was characterised by a constant state of emergency.

Of course, the workers and peasants could have easily swept aside the reactionary forces but the left leadership instead pursued the policy of the People’s or Popular Front.

So, when Franco’s forces mobilised, the Socialist and Communist party leaders pinned their hopes of victory not with the working class and the revolution; but on the restoration of the bourgeois democratic government – placing their faith in the Republican bourgeois to defeat Franco.

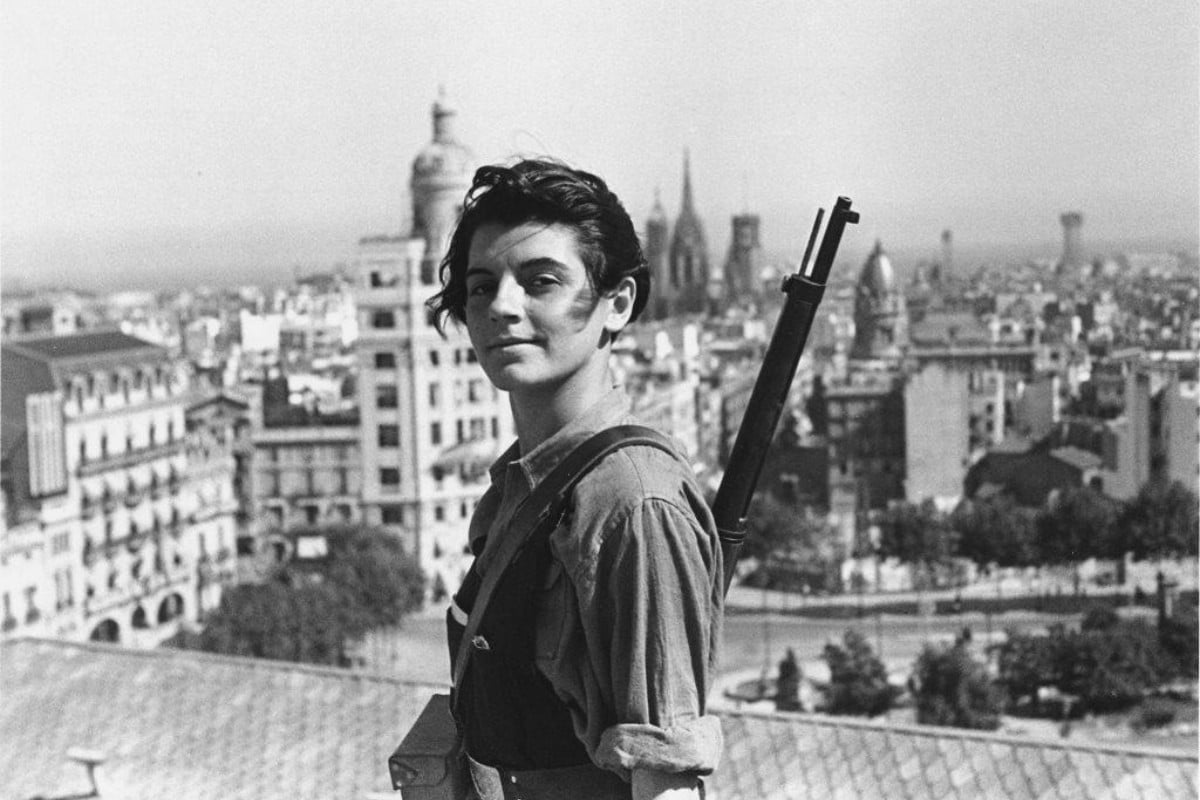

Despite this, the workers organised and armed themselves almost immediately in defence of the revolution. They were far in advance of their own leadership. In many factories and workplaces there were elements of workers’ control and for periods workers essentially controlled the streets.

Questions for discussion

- What was the political situation in Spain at the time Morrow’s book was republished in 1973? And what was the reason for republishing it?

- What similarities did the Spanish and Russian bourgeoisie share that prevented capitalism developing earlier?

- What impact did the coming to power of Hitler’s fascist regime in 1933 have on the consciousness of the Spanish as well as international working class?

- What similarities are there when comparing the Menshevik and Social Revolutionaries’ position on the Provisional Government in the February Revolution, with that of the position of the Spanish workers’ parties on the Popular Front government in 1936?

- How did the workers respond at the beginning of the fascist insurrection? What role did the workers’ parties play?

- What impact could the success of the revolution have had on the Soviet Union and its bureaucracy?

- Ted Grant uses the example of the Bolsheviks as well as Mao and the CCP to demonstrate the need to fight a civil war as a social struggle to win. How could the workers’ parties have done this in Spain against Franco?

Chapter 1: Why the Fascists revolted

The first three chapters of the book provide some context and set the economic and political scene of the period before the Spanish civil war, and they begin to explain why Spain’s ruling class decided to resort to Franco’s programme rather than continue as they previously had.

Chapter one deals primarily with the social and economic basis of fascism in Spain, and why Franco was supported by the capitalist class at this particular time. This was happening at a time when Spain was economically backwards compared to a lot of the European powers. The chapter explains that although 70% of the population lived on the land, the division of that land was the worst in Europe, with two thirds of the land held by big landowners or in large estates, and the remaining third left technologically underdeveloped and split between huge numbers of peasants. Despite agriculture being Spain’s main source of income, the average yield of the land was the lowest in Europe.

In these conditions, the ruling class were keen to avoid any and all concessions to the working class, which led to both increased repression of workers such as during the ‘two black years’, but it also led to further struggles in the labour movement, such as the huge strike wave between February and July 1936. With the ruling class unable to afford concessions and the workers becoming increasingly class conscious, fascism became a necessary last resort for the capitalists.

Questions for discussion

- Morrow explains that Franco’s programme was “identical in fundamentals” with that of Hitler and Mussolini. What are some examples of this?

- Why did the economic backwardness of Spain and its weakened position in the world market mean that the ruling class was less tolerant of workers’ and peasants’ organisations?

- Why is it wrong to say, as the Stalinists did, that fascism in Spain was based on feudalism?

Chapter 2: The Bourgeois ‘Allies’ in the People’s Front

This chapter discusses the resistance against the rise of Franco, specifically the Popular Front. There is a lot of detail about the different bourgeois organisations that were involved in the Popular Front, from Basque Nationalists to bourgeois republicans. All of them had an extensive history of collaborating with extreme reactionaries, suppressing workers’ movements, downplaying the threat of Franco etc.

The chapter points out that for these bourgeois groups, even though they were in the so-called Popular Front against fascism, their petty-bourgeois class interests meant that they would ultimately always have more in common with the defenders of capitalism than with the workers.

Questions for discussion

- What does the reactionary history of the bourgeois parties in the Popular Front show us about the effectiveness of the popular front method of fighting fascism?

- What is the difference between the suppression of workers under fascism and the ‘suppression’ of the liberal bourgeoisie? How does this impact their willingness and ability to fight fascism?

Chapter 3: The Revolution of July 19

This chapter describes how in many areas, and particularly in Barcelona, the working class, represented by organisations like the CNT or the POUM, fought back against army barracks that had declared their support for Franco. Armed with guns, dynamite or even just their fists, workers built barricades, distributed weapons and built an army of workers that could face the army that was behind Franco.

As well as organising in order to physically oppose fascism, however, workers’ organisations also began the reorganisation of the economy and industry in order to better use it for their revolutionary purposes. Where possible, workers’ committees took control of transport, factories and all areas of production necessary for the fight against fascism. The chapter points out that these efforts were not always the most successful or efficient, but their weaknesses were primarily due to the weakness of Spanish industry and the inevitable hastiness that the situation demanded, rather than due to any lack of heroism from the workers.

Questions for discussion

- Why did the workers of Catalonia reach revolutionary conclusions more quickly than those in other areas of Spain? What are the similarities between this and, for example, Petrograd in 1917?

- What are the characteristics of the dual power that began to develop after the ‘revolution of July 19’?

Chapter 4: Towards a Coalition with the Bourgeoisie

This chapter starts with the Days of July. It explains that reformists are the main prop for bourgeois governments in times of dual power. There was no army that the government commanded, and much of the police had been swallowed up into the workers’ militias.

The government scorned the workers for taking over factories, for seizing land, but at the same time it did not purchase arms – despite its gold reserves – with which to destroy the threat of fascism.

Morrow starkly highlights the lack of revolutionary leadership. Throughout most of the country, the situation and opportunities for the workers were far more favourable than the situations in the German revolution and in Russia before 1917.

The government had no army; the people were rallied to fight the fascist insurgency; locally there were armed militias, and a mushrooming of organs of workers’ power. But no attempts were made to generalise these; these organs of workers power were never centralised into soviets and workers’ councils linked up nationally.

Without the perspective being raised for a workers state, and the brushing aside of the bourgeois government, the leaders of the CNT and POUM entered into collaboration with the government. None of this was explained, and was bound to leave the masses confused and disorientated.

Similarly, this chapter reveals the weakness of the revolution’s leadership in not taking hold of the commanding heights of the economy – most specifically the banks. As capitalism was not overthrown, its laws continued to function. Finance capital was used to curb the workers movement with the flight of capital, run on the currency, etc.

Question for discussion

- Why would the bourgeoisie want workers’ leaders in the government?

- What was the main problem or limitation of workers’ power in the Spanish revolution?

- What was different about the way in which the Bolsheviks fought the Kornilov coup and how the anarchists and the POUM fought the fascist insurgents?

- Why were workers (producers) cooperatives still subject to the laws of capitalism? What is necessary for workers’ control to rise above capitalist economics?

Chapter 5: The Politics of the Spanish Working Class

This chapter analyses the politics of the ostensibly left wing parties and tendencies.

Much of the right wing socialists are described as petit bourgeois republicans, cut from the same cloth as Azana who had used his premierships to crush strikes and the movement of the peasants.

The Stalinists practiced open collaboration with the bourgeoisie. They shared the same aim: to prevent a successful workers’ revolution in Spain. What is interesting is who they recruited: conservative labour leaders; petit bourgeois politicians, businessmen, manufacturers.

The anarchist CNT proved in practice the falsity of the anarchist ideas on the nature of the state. Because the anarchists blur any distinction between a workers’ state and a bourgeois state (for them, they are both simply ‘authoritarian’), they participated in the existing bourgeois government, which seemed to them less ‘authoritarian’ than forming a new workers’ state which would overthrow and destroy the bourgeois state.

The chapter points out that the POUM could have undertaken the task of organising soviets. They seemed to think they could use the liberals to their own ends, but instead it was the POUM who were hung out to dry once they had been discredited by the coalition with these liberals.

Questions for discussion:

- How did the policies of the Seventh Congress of the Comintern stand in complete opposition to the policies of the Communist International under Lenin and Trotsky?

- Why did the Stalinists call for the liquidation of the workers’ militias?

- What is wrong with the ‘theory’ that Spain needed no soviets?

- Why was limiting the struggle to solely ‘seeking control of the factories as the real source of power’ doomed to fail?

Chapter 6: The Programme of the Caballero Coalition Government

This new coalition government talked about ‘liberty’ and the need to defend the republic. But this was the same republic that had shot trade unionists, put down factory occupations, and generally undermined the workers’ movement at all opportunities. All of which was done because this allegedly ‘provisional revolutionary government’ was committed to maintaining the ‘old bourgeois order’. In turn this meant basing itself on appeals to aid from the ‘great democracies’, i.e. the major imperialist powers. For these reasons, the government also refused to listen to demands from Morocco for freedom from Spanish colonialism, thereby squandering a base of support for the revolution in North Africa and against Franco.

As a result, the talk of ‘liberty’ was abstract, no material gains or changes for the working class or peasantry were forthcoming, and therefore the working class became demoralised at seeing their leaders participate in this process.

Questions for discussion

- Caballero put his hopes in winning over the ‘great democracies’ of Britain and France in fighting fascism. What were the ramifications of this strategy?

- How would the blockade best have been fought?

Chapter 7: The Programme of the Catalan Government

This chapter begins attacking POUM leader Nin’s typical zig zagging style of centrism. Nin cried ‘down with the bourgeois ministers’, but a few days later his own CC accepted a coalition with them. This demonstrates his lack of foresight, or his not taking revolutionary slogans and the struggle for power seriously.

The POUM CC justified its coalitionism with the claim that the Catalan government is ‘profoundly popular’, leaving its class character unanswered. This statement is full of revolutionary sounding desire, it implores the government to build the revolution, but it is all vague and wishful thinking. It says the Catalan government’s working class supporters are moving to the left – Morrow mocks them for thinking the way to win these workers is by giving their leaders a left cover. We can see that Nin was fudging questions, and substituting agreements at the top for the mobilisation of workers. He celebrated dual power, pretending that one side of this duopoly could help foster the other, rather than being in life or death struggle with it.

And yet as he said these ‘revolutionary’ phrases, he signed decrees handing power to the bourgeoisie, only to then be kicked out of the government. Thus the POUM, as all other tendencies, betrayed the Spanish revolution.

The chapter explains that the compensation given to capitalists was used to crush the workers cooperatives, because this compensation was paid not on a national basis, but by each cooperative shouldering the entire burden. This shows how workers’ control by itself – ie without state power, the anarchist ideal – was just cooperativised capitalism. Each cooperative must sink or swim according to market pressures. Morrow also explains how the structures of collectivisation were also designed to inhibit the working class and gum up the revolution.

Questions for discussion

- What does the entry of the POUM into the Generalidad, or the existence of ‘all workers’ cabinets in other countries with bourgeois states, demonstrate about the nature of the bourgeois state and democracy?

- How do the errors of Nin’s comments on dictatorship of the proletariat help us to understand the nature of the workers’ state?

- How did POUM leaders justify entry to Generalidad?

- What did the Generalidad do on 19 July? And what on October 27 1936? What does Morrow characterise these acts as signifying?

- What did the failure to nationalise the banks mean for collectivised industries?

- Why did POUM and CNT fail to send delegations abroad to campaign amongst advanced workers for solidarity?

Chapter 8: The Revival of the Bourgeois State: September 1936 – April 1937

The chapter starts by explaining how the bourgeois governments in Madrid and Barcelona used state power to gradually whittle away the economic gains of workers and peasants, banning collectivisations, abolishing the workers’ supply committees, and allowing landowners to get their land back under cover of being ‘co administrators’.

The radio stations of the POUM and CNT were curtailed. This repression shows that the weakness of these parties only invited aggression. In the repression of the POUM and CNT, and the workers’ militias, the role of Stalinists in recruiting fascist thugs was important.

The army was eventually reorganised under bourgeois command, with workers’ democracy liquidated, because you cannot have a workers militia of a bourgeois state. The POUM leadership prevented democracy in its own militia to preserve the bureaucracy’s control.

Questions for Discussion

- What attitude did the Generalidad display towards the workers’ organisations it was formally in coalition with?

- Interestingly, Morrow attacks the banning of the newly revived police from joining a union, as ‘quarantining the police against the working class’. How does this relate to sectarian ultra leftism regarding the police today?

- What ultimately was decisive in allowing the government to reorganise the militias under their command? What should have been done?

Chapter 9: The Counter-Revolution and the Masses

This chapter explains that after all this repression, the CNT capitulated even more thoroughly to Companys after threats from the Communist Party. Morrow points out that the CNT leaders can afford their own capitulation, but the masses could not. Price rises, thanks to the return to the market and the hoarding of middlemen, were astronomical.

The Friends of Durruti arose as a sort of Bolshevism against the betrayal of anarchist leaders. But the lack of a revolutionary party slowed this process of organising a left opposition within the anarchist ranks. The POUM failed to win such layers. The POUM again spoke in revolutionary terms, but addressed themselves to the government, not the workers. It even focused its ‘revolutionary’ demands around the appeal for a place in the government once again. In reality their radical proposals were simply words to placate their left wing base.

The chapter ends with a good account of what Soviets are, explaining their directness and their broad base, which together allow for the most flexible, up to date expression of working class political development, and thus are ideal for a revolutionary organisation to fight within for leadership of the working class. Morrow criticises Nin’s fetishisation of a multiparty regime within soviets as a fudge to avoid taking power whilst the other workers organisations are reformist. An excuse, as is always found, to cling to the coattails of reformists, who in turn cling to the bourgeois.

Finally, Nin clamps down on his own party as the ranks declare in favour of creating Soviets.

Questions for discussion

- What was the significance of the creation of the Friends of Durutti?

- Why was it ridiculous for the POUM to propose a revolutionary programme to the government?

- Why did Nin clamp down on democracy within the POUM?

Chapter 10: The May Days: Barricades in Barcelona

In this chapter we see the conflict between the aspirations of the workers and the gradual return to bourgeois ‘normality’ come to a head with the May Days of 1937.

The Catalonian working class was the backbone of the anti-fascist forces at this time. Industries under workers’ control, such as textiles, chemical, and metal, could have helped equip the anti-fascist army.

But the CNT, having just rejoined the Generalidad, was receiving pressure from the government to break down workers’ control. They capitulated, trying to find a so-called peaceful solution.

The immediate cause of the uprising in Barcelona / Catalonia was the attempt of the Stalinists to seize control of the telephone exchange for the Catalan government. The control of the telephone exchange marked one of the gains of the revolution of July 19th, which the CNT workers had seized and controlled and guarded since then. Morrow notes how this is a concrete example of dual power at this time.

As news of this seizure spread, the working class built barricades, their tradition of local defence committees providing leadership for this. Stalinist headquarters were also seized by CNT and POUM militants as a preventive measure. Morrow says that this showed the masses of Catalonia, overwhelmingly under the banner of the CNT, could have formally seized Barcelona which would have led, in a very short space of time, to working-class power.

We continually see the bankruptcy of the POUM-CNT leaders at such a critical point. There are countless examples in this chapter, such as promising to ensure workers’ troops didn’t advance in return for no more government troops in Barcelona, only to let more of these troops in when they heard they were coming anyway.

The intuition of the working class was right: “Again, as the workers saw the government forces continue the offensive, they returned to the barricades, against the will of both the CNT and the POUM”. But there was no organisation with deep enough roots in the working class to offer an alternative leadership.

Questions for discussion:

1. Why did the attempt to seize control of the Telefonica provoke such a militant response from the working class?

2. What was the role of the Stalinists in this?

3. If the workers’ republic would have been established in Catalonia, why would it not have been isolated or crushed?

4. How could a workers’ republic have fought against the fascists at this point?

5. What was the response of the CNT / POUM to the uprising?

6. How did this strengthen the counter-revolution?

7. Why was the parallel of May with July 1917 in Russia wrong?

Chapter 11: The Dismissal of Largo Caballero

The defeat of the masses after the May Days in Barcelona marked the beginning of the advance of the bourgeois-Stalinist counter-revolution in the Spanish Republic. The centrist leaders of the working class, in the UGT/PSOE, POUM and CNT-FAI had all along obscured the consolidation of the reactionary bourgeois-Stalinist bloc within the Popular Front and were now to be dispensed with by the counter-revolution.

The Stalinists quickly understood the need for the suppression of the POUM and CNT in order to decapitate the working class, before liquidating all the gains of the Revolution: workers’ control in industry, collectivisation of the land, workers’ militias and supply committees etc. Well versed in the methods of police state terror, political slanders and frame-ups, the Stalinists acted in service of Anglo-French imperialism and the Spanish bourgeoisie by pacifying the working class.

Morrow explains that the fundamental aim of the Spanish republican bourgeoisie and imperialism was to reconcile with Franco and thus end the civil war and finally crush the proletarian revolution.

Largo Caballero, owing to his mass popularity in the UGT, proved to be a difficult obstacle. Also as Defence Minister, Caballero came into conflict with the programme of the bourgeois-Stalinist bloc for the dissolution of the workers’ militias at the Front and workers’ control in war industries. Despite attempts by Caballero and the left-Socialists to placate the right, he was dismissed in favour of Juan Negrin (a right-wing Prieto-Socialist).

Questions for discussion

- Why did the bourgeois-Stalinist bloc need to dismiss Caballero?

- How were the centrist leaders of the POUM and CNT useful to the counter-revolution before and after the May Days?

- Why were the Stalinists able to ‘absorb’ the left-Socialists?

- Why was the re-opening of the Churches important to the counter-revolution?

Chapter 12: ‘El Gobierno de la Victoria’

The counter-revolutionary Negrin government was hailed as the ‘Government of Victory’ by its supporters, not least the Stalinists. This phrase attempted to conceal the re-establishment of the supremacy of the bourgeois state over the working class, and the dismantling of what remained of dual power. The international bourgeois press openly recognised this, calling it a government of ‘order’ that would remove the influence of ‘extremists’.

The revolutionary tribunals that had been established to suppress fascists and reactionaries were subverted by the return of right-wing bourgeois judges, and turned against the working class. While special courts jailed workers, the censor punished criticism of the Stalinists and the Catholic Church, and revolutionary radio stations were shut down, known fascist-sympathisers were given amnesty and released.

Resistance put up by workers and peasants to the bourgeois-Stalinist opposition to land seizures and workers’ control was smashed by the police, paving the way for the return of the old bosses and landlords. In the countryside, the hated overseers and enforcers of the landlord class returned – now holding Communist Party membership cards.

Reactionary ministers were invited back into the Government, happy to work alongside the Stalinists and opportunists in the ‘reconstruction’ of Spain. The Communist Party justified this on the grounds that only their inclusion gave legitimacy to the Government, on the basis of a parliamentary majority in the February 1936 elections. The power of the working class asserted by the July 19 Revolution was thus declared illegitimate, and effectively dissolved in favour of the bourgeois Cortes. Morrow asks: “Was it for this then that the masses shed their blood?”

Questions for discussion

- How did the bourgeois-Stalinist bloc oversee the counter-revolution in the countryside?

- How did anarchist errors on the nature of the State endanger workers’ control of industry?

- How was the bourgeois-Stalinist bloc’s industrial programme of ‘state control’ and ‘militarisation’ different from a socialist programme?

Chapter 13: The Conquest of Catalonia

Once Catalan autonomy had been crushed, the Bourgeois-Stalinist bloc proceeded in earnest with the counterrevolution in Catalonia.

Immediately they took action to crush the POUM – using the methods of the Stalinists in the USSR – labelling them as fascists, agents of the Germans, Italians, etc.

The POUM press and radio were seized, the Friends of Durriti’s headquarters were occupied, the organisation outlawed. The anarchist press was put under iron censorship.

But the POUM and CNT leaders didn’t join together in protest, or organise a united front to defend themselves – because this would have meant admitting that their previous policy was wrong. The POUM was then outlawed, and its leaders arrested.

Morrow explains that only the Bolshevik-Leninists (Trotskyists) put forward a correct programme for struggle – but they were too small to win leadership of the masses.

The Stalinists then began pogroms against the left – night raids – arresting and assassinating leading members of the POUM and CNT.

By the end of June all Catalan autonomy had been smashed. Police had been transferred to other parts of Spain (except the most reactionary section), even the firemen transferred to Madrid. This was in order to remove radicalised and organised workers so the Stalinists could proceed without effective opposition.

Parades were forbidden, union meetings could only be held at three day’s notice, under permission from the delegate of public order. Workers’ patrols had been wiped out – most active members had by now been imprisoned.

Morrow points out that all of this was done under the screen of the CNT ministers sitting in the government! But now the Stalinists felt the time had come to dispense with the CNT. Their purpose had been served.

It is also explained how the counterrevolution struck against the peasant collectives by sending tens of thousands of Assault Guards. The peasants tried to defend themselves, but the lack of centralised direction meant they were overpowered.

Workers’ collectives in industry were also wiped out – although due to a mass campaign of the transport workers’ union, they managed to hold control over Barcelona transport system.

Questions for discussion

- How did the actions of the POUM and CNT leadership assist the counterrevolution in suppressing their organisations? What should they have done to defend themselves?

- Why did the Stalinists now break with Companys?

- How did the bourgeois-Stalinist bloc carry out the counter-revolution in industry?

- What effect did keeping the struggle within the bounds of bourgeois-democracy have on the morale of the working class?

Chapter 14: The Conquest of Aragon

Aragon was the only province to have been under fascist control, and then taken by the CNT and POUM militias. These forces had been led by Durruti and were organised as an ‘army of social liberation’. All the large estates were confiscated and handed over to the village committees. Voluntary collectivisation led to big increases in agricultural production.

In practice, the anarchists leading Aragon abandoned anarchist federalism in favour of centralism, out of necessity.

But despite the strength of the revolution in Aragon – in fact precisely because of it – the bourgeois-Stalinists had to reconquer it. They laid the basis for their invasion with a campaign of lies about the regime in Aragon throughout Spain.

Questions for discussion

- What was key to the success of the left militias in conquering Aragon?

- How did anarchist principles break down in practice under their administration?

- How did the bourgeois-Stalinist bloc retake control of Aragon?

Chapter 15: The Military Struggle under Giral, and Caballero

Morrow explains that the military strategy followed by the Giral cabinet ultimately reflected their political outlook. Despite having adequate resources at their disposal, they failed to arm the masses. This led to regions such as Irun falling to the fascists.

Caballero’s cabinet followed suit in failing to organise the navy appropriately. For the Spanish bourgeoisie, the desires of Anglo-French imperialism mattered more than fighting facism. Despite the betrayal of the popular front government, the masses consistently showed their determination to organise and fight the fascists.

The Stalinists began to provide military support for Stalinist controlled areas only. On top of this, they argued for the need to liquidate militias into the bourgeois army. All of this, taken together, led to the fall of the Aragon front.

The setbacks in Aragon, and Basque, allowed Franco to push on to try to take Madrid, which was controlled by the Stalinists. The defence of Madrid became an absolute priority. Methods of defence that were actively subdued in other regions, were suddenly provided for here. Revolutionary methods that called for workers committees through the streets were now called for by the Stalinists. This is what was needed everywhere. But in all other fronts these methods were actively suppressed.

Questions for discussion

- How did anti-revolutionary politics reflect itself militarily?

- What general lesson should we take from the general strike in Saragossa?

- What is the ideological basis of a united front?

Chapter 16: The Military Struggle under Negrin-Prieto

Under the Negrin-Prieto cabinet there was a further move to the right, particularly on the national question. Unlike the Bolsheviks, who sought to win over oppressed minorities, the Negrin-Prieto cabinet exacerbated divisions by failing to grant autonomy to different regions. The fascists and monarchists were known for their oppression of national minorities. By more or less repeating the same policy as the fascists regarding the Basque country and Catalonia, this regime undermined the struggle against the fascists.

The government continued to seek to isolate and wipe out POUM regiments by sending them into doomed battles. The POUM militias fought so well that this plan was undermined. They resorted to disarming the militia after its successes. Anarchist divisions were not paid for months so that they were too weak to fight.

In some cases the demoralisation at this leadership was so extreme that troops passed over to the side of the fascists, but the anarchist press was prevented from reporting this as it embarrassed the Stalinists.

Morrow explains that the Basque capitalists openly sabotaged the struggle against Franco on account of their class interests. In this they were aided by ‘democratic’ Britain. In contrast, the Asturias, held by CNT and left Socialist forces, fought doggedly against fascist invasion, causing the latter huge amounts in materiel and men. However, the Asturians were betrayed by the central government, who left them isolated.

Questions for discussion

- Why would a ‘declaration of autonomy for Galicia immeasurably facilitate the guerilla warfare there?

- Why did the Basque bourgeois surrender?

- What was the difference between the military in Oviedo and Gijon?

Chapter 17: Only Two Roads

By this point, Morrow is describing revolution in full retreat.

The imperialists for whose support and approval the Stalinists had sacrificed and destroyed so much had no intention of seriously intervening on the side of the Loyalist government of Negrin.

It was clear that the imperialists expected a Franco victory, or a compromise largely favouring the fascists, and were already making preparations for this outcome.

The only reason they didn’t openly court Franco at this time is they saw war in Europe coming, and they needed to preserve the myth of democratic war against fascism to mobilise their own working classes behind them.

They did also want to edge out the German-Italian imperialist bloc supporting Franco, without being drawn into an open confrontation, if possible.

Even the Stalinists in their press were forced to admit that the imperialists regarded the war in Spain as a ‘secondary consideration.’

While it was clear that Franco expected and was seeking total victory, the imperialists and Stalinists tried to stitch up the basis for a “non-intervention agreement”, in which they would broker a ceasefire in return for a raft of concessions to the fascists.

Stalin readily accepted this plan. His main consideration at this time was to maintain his arrangement with French imperialism in particular (this was before the pivot to the non-aggression pact with Germany in 1941).

The Communist International instructed the communist parties around the world to agitate for worker activists to protest for their ‘democratic governments’ to come to Spain’s aid – a policy of, on the one hand, abandonment of revolutionary war, on the other, lining up workers behind their respective governments for the coming world war.

While all this was going on, the Moscow trials and their aftermath saw open attacks on Trotskyists and their ‘allies’ (genuine or otherwise) all over the world – in part using the slander that the POUM had assisted the counter-revolution in Spain.

Questions for discussion

- What were the ‘two roads’ that Morrow sets out at the start of the chapter?

- Why did Anglo-French imperialism refuse to seriously assist the Popular Front government in defeating Franco?

- What would a compromise with the fascists have entailed? What conditions would it have involved and what would have been the consequences?

- Summarise the condition of the main, non-Stalinist workers’ organisations: the CNT, the UGT, the POUM and the Friends of Durruti

- What does Morrow lay out as the main tasks for the Fourth Internationalists in Spain?

- Discuss how Stalinism internationally acted in an increasingly counter-revolutionary manner.

Postscript

In the postscript, written just as he was going to press, Morrow talks about the jailing of workers and peasants and the opening of the front lines by ‘republican’ officers to the fascists.

General Sebastian Pozas adequately symbolizes the period: he was an officer under the monarchy; an officer under the republican-socialist coalition of 1931–1933; an officer under the Lerroux-Gil Robles bienio negro of 1933–1935; a Minister of War before the fascist revolt broke out.

When Catalan autonomy was done away with and the CNT troops were at last subordinated entirely to the bourgeois regime, Pozas was appointed chief of all the armed forces of Catalonia and the Aragon front.

He purged the armies of the CNT and POUM, arranging for whole divisions to be wiped out by sending them out under fire without artillery or aerial protection.

The consequences of the alliance with the ‘republican’ bourgeoisie, of the People’s Front programme, were now apparent: Franco’s victory. Morrow states that the Stalinists, the Prieto and Caballero socialists, the anarchist leaders, proved insurmountable obstacles on the road to regroupment, facilitating Franco’s victory.

This defeat set the stage for four decades under the fascist jackboot, until the revolution in 1970s

Questions for discussion

- In his post-script, what does Morrow say is the ultimate objective of his book?

The Civil War in Spain

Introduction

In the introduction, there is an anecdote that gets to the heart of the problem with the Spanish civil war. When the workers’ militiamen call on the fascists to join the struggle for the Republic, they shout back ‘What did the Republic give you to eat?’ With the programme of the coalition government being presented as a military and not a social one, it is easy to understand why the cause of the republic did not galvanise much of the peasantry.

The need for presenting a revolutionary socialist programme was crying out in Spain. The masses, after the experience of the early 1930s, would clearly not be galvanised by a cause that had continued to repress them and failed to solve the tasks of the bourgeois democratic revolution. A comparison is made with the French revolution and Bolshevik sloganeering.

Questions for discussion

1. What was the weakness of the slogan ‘Defend the Democratic Republic’? How does Morrow counterpose it with the sloganeering of the Bolsheviks?

Chapter 1: The Birth of the Republic – 1931

Morrow begins talking of the birth of the republic. The sweeping aside of Alfonso was the easy part, what was to follow was turmoil and civil war. The situation in Spain was conditioned by world relations at the time. Though Alfonso appeared to do relatively well in WW1, profiting off neutrality, Spain was no match for the dominance of the victors (‘Great democracies’) in the aftermath.

This gave rise to a mood of radicalism – encapsulated by the militancy of the youth. The tide had turned enough by 1931 for the monarchy to realise this was not a fight they could win.

The most established republican parties – like the radicals – actually did nothing to bring the Republic about. They themselves were very comfortable with the monarchist regime, and had already established very lucrative posts. Hence, there was no political leadership from the very start.

The real support for the republic was led by the rank and file of the trade union organisations like the UGT. But they were also woefully unprepared for the task at hand. The petit bourgeois outlook of figures like Azana confirm this. They based themselves on the false theory of two stages.

The CNT had similar limitations, based on their anarcho-syndicalism, that the revolution must only take place in the factory. Leaving politics to one side, they were initially passive on the developments of the republic.

Questions

- Why do you think Spain’s empire had something to do with the failure of Spanish revolutions before the 1930s?

- Why do you think the young Spanish bourgeoisie were so loyal to the crown?

- Who would the task of overthrowing the monarchy fall to? What does this signify?

- What were the main tendencies of the Spanish working class by the 1930s? What were their weaknesses?

Chapter 2: The Tasks of the Bourgeois-Democratic Revolution

Morrow explains the tasks of bourgeois democratic revolutions, and the problems that were faced in Spain.

The agrarian question is described graphically, revealing just how important this question was. Morrow makes a very good comparison to France and the Jacobins. But there is a key difference: by now the land in Spain was exploited on a capitalist basis, and so land reform would have threatened the interests of the capitalists rather than enabled the development of capitalism, as in the French revolution.

Morrow discusses the weakness of Spanish capitalism, which was cruelly revealed with the end of World War One. Spanish capitalism, less competitive than that of France and Britain, could not develop in a contracting world market, as was the case at this time. However, as with Russia, the lateness of its capitalist development meant there was a large, powerful proletariat concentrated in a few key cities.

The Church’s extraordinary power and vast landholdings are explained, which was the basis for the deeply reactionary role it played in relation to the new Republic after 1931.

Morrow explains the history of the Spanish army and the building up of a privileged officer caste, which was a grave danger to the new Republic. But this new Republic did very little to the army or to diminish the power of this officer caste.

Spain’s colonial conquests in Morocco are explained as capitalist in character. The Republican ‘socialist’ regime of 1931 continued and maintained this colony. Morrow points out this not only means oppression for the Moroccan people, but also poses a serious danger to the Spanish working class, since this militarised territory could and would be used as a base for Spanish reaction, as indeed proved to be the case with Franco.

Similarly, it would be essential for the new regime to grant the right of self determination to Catalonia and the Basque country, and to immediately end their national oppression, so as to cut across the rise of Catalan and Basque nationalism and to forge unity in the working class across national boundaries. The republican-socialist government failed to do so.

Questions for discussion

1. Why was the monarchy ‘thrown to the wolves’ by the industrialists?

2. Why did Trotsky predict the impossibility of the bourgeois republic carrying out the tasks of the revolution? How does this relate to the theory of permanent revolution?

3. What was the importance of Spanish industry being developed ‘under protection of a monopoly of foreign trade’?

4. Why did the Church’s influence need curbing?

5. What does Morrow mean when he writes: “The liberty of the Spanish masses would be imperilled unless the colonies were freed”?

Chapter 3: The Coalition Government and the Return of Reaction, 1931-1933

These chapters give a clear account of the sweep of revolution from 1931-6, a movement so strong none of the reformist or Stalinist leaders could contain it.

It begins with a description of mass burning of churches in 1931 in response to the counter-revolutionary role of the Church. Massive fights between workers and monarchists broke out. Revolutionaries also demanded the arrest of monarchist leaders, but the Socialist leadership preached calm and worked with the police. The government calls for martial law.

This government, a popular front, was based on the false idea that this was a bourgeois revolution and therefore it was necessary to strengthen the bourgeoisie. Socialist leaders ignored Marx’s conclusion of 1848 that workers and socialists must fight independently of the wavering petty bourgeois.

Instead, the Socialists declared Spain a ‘republic of workers of all classes’.

The new constitution gave the vote to over 23s and made representation of minority parties almost impossible. It was designed, like the US constitution and Weimar, to keep everything as it is. It was also very explicitly anti-working class: there were massive restrictions on strikes, the workers’ press etc. The Socialists thought their coalition with the bourgeoisie would go on indefinitely.

As if to make the bourgeois domination of the Socialists clear, when the Socialist Prieto became Minister of Finance and tried to take control of the Bank of Spain, a scandal was created and he was promptly removed.

Despite this, the workers militia was simply organised as a defence of this counter revolutionary government. Government troops crushed the CNT in Jan 1933.

Sensing an opportunity to win support from workers and peasants disappointed with the anti-worker policies of the ‘socialist’ government, the Monarchists decided to change tack and to demagogically defend peasants who were attacked by the regime. They even attacked the government for banning workers’ papers. Their exploitation of this discontent

led to a big electoral victory for the monarchists in November 1933.

Questions for discussion

1. Why did Socialists help the police and establishment of martial law? What was their perspective?

2. What was the main lesson of the German and Austrian revolutions?

3. Why does seeking to democratise the bourgeois state not mean supporting it?

4. What must a ‘real proletarian militia’ not do, and what must it do?

5. How did the monarchists change tactics in order to undermine the bourgeois republican regime?

Chapter 4: The Fight against Fascism, November 1933 to February 1936

For the next two years, Lerroux’s ‘Radicals’ were generally at the helm. These were the ‘two black years’.

Over 100 issues of El Socialista were seized by this regime in a year. In September 1934 12,000 workers were imprisoned.

Gil Robles’ clerical fascists remained weak (because the middle class was small) and were smashed by workers. The Spanish workers quickly moved to the left after the defeat of the German revolution.

The leftward turn the Socialists now made enabled the defeat of Robles’ fascists, however they were still confused and afraid of insurrection.

In their leftward turn they refused to call for anything that would involve participation in bourgeois democracy, such as the dissolution of the government and new elections. On the other hand, they also saw the need for broader unity purely in terms of agreements between leaders, and not in terms of mobilising the masses of different workers’ parties. The Socialists saw everything from above, the role of the masses was conceived as passive.

However, so strong was the upward, militant mood in the working class, that even the Stalinists had to abandon their ‘Third Period’ ultra-leftism and join the Socialist led protests.

A nationwide general strike was declared after Robles entered the Lerroux government in October 1934. This failed due to lack of preparation with the CNT.

However it was very militantly carried out, and in Asturias thanks to a more leftwing leadership, it established the commune.

As a result of many further strikes over the next year, the government wavered and retreated. It then collapsed and in elections the left were swept to power. But Socialist leaders, in power again, repeated all the same dampening ‘go back to work’ phrases from 1931-3.

Questions for discussion

1. Why did Gil Robles struggle in getting a mass base? Who did he turn to, and how?

2. How did the Socialists (erroneously) understand the need for broader unity?

3. Why did the general strike against Robles’ entering the Lerroux government in October 1934 fail?

Chapter 5: The People’s Front Government and its Supporters: February 20 to July 17 1936

The new Azana government’s programme was explicitly against agrarian reform, against bank nationalisations and unemployment benefits, against touching the church except to remove it from state education, against democratisation of the army, with little autonomy for Basque country and Catalonia, and no liberation for Morocco, no workers’ control in industry.

Once again this regime quickly showed how reactionary it really was – workers were arrested, strikes and demonstrations ruled out, massive censorship of workers’ press was imposed, anarchist and communist offices were forced shut, and hundreds of strike leaders were arrested. At the end of the day, it was led by bourgeois politicians who could not tackle reaction, because they could not touch the economic foundations of reaction. But because the Socialists and Communists had the perspective of supporting the bourgeoisie, they were incapable of leading opposition to these reactionary methods, and in fact once again gave a left cover to them.

Question for discussion

1. What is the limitation of voting blocs, and how should revolutionaries avoid this?

2. What were the agrarian and economic policies of the programme of the People’s Front? What does this tell us about ‘common programmes’ with liberals?

3. What did this programme make inevitable?

Why is maintaining an Officers’ Corp so important for the bourgeoisie? What should it be replaced with?

Chapter 6: The Masses Struggle against Fascism despite the People’s Front

The people’s front government took no time in revealing its class nature. Meanwhile, the masses took no time in getting on with the job of confronting the fascist affront. Azana, leading the government, constantly appeases reactionary elements, attacking the proletariat. This emboldens the fascists in their attacks against the workers.

Despite the government’s efforts, the mood amongst the workers was increasingly militant, and reflecting itself in strikes. Azana quickly realises the best way to quell this mood is to use the workers’ leaders themselves. Prieto from the Socialist Party is invited to join the cabinet. This poses important questions for the party, as outside elements push for him to join. This reveals different class pressures being put on the party and its leaders. Caballero feels the weight of the rank and file, and dares not jeopardise his following at this stage.

Questions for discussion

- Why did the bourgeoisie want Prieto in government? What does this show about their outlook?

- Why did Prieto not enter the cabinet?

- What does the number of strikes tell us about the nature of a revolutionary period?

Chapter 7: Counter-Revolution and Dual Power

As Franco seizes Morocco, Azana, the people’s front government and the Stalinists attempt to water down the situation, and refuse to arm the workers.

Despite the passivity of the government, the working class, sensing the real threat of fascism and danger, begin to mobilise independently. In key areas such as Madrid and Barcelona, we see the workers organise to defend themselves and their towns, with whatever arms they can get hold of.

This independent action represented a significant development. The workers had developed their own mechanisms of power alongside that of the state. This was a situation of ‘dual power’ that Lenin describes in the Russian revolution.

In Catalonia, the situation reached a fever pitch. Factory committees were organised, and a political programme developed. The experience of Catalonia proved why revolutionary methods were the only way to confront the fascists.

In Madrid, the Stalinists continued to play a treacherous role in handing power over to the bourgeoisie. They make clear they are against the idea of a workers’ state at this stage. Their anti-proletarian character is further expressed when they support the Azana government’s attempt at creating a new army.

Caballero’s entry into the government is met with genuine enthusiasm by sections of the proletariat. But this alone is not a solution, as he enters without a clear programme. The lessons of Catalonia remain for everyone to see, but the correct leadership is non-existent, and unable to take those lessons to the masses.

Questions for discussion

- What should working class militia defence look like?

- Where was the People’s Front weakest and why?

- What made the Catalonian proletariat so successful?

- Compare the slogans ‘All power and authority to the People’s Front Government’ and ‘All power to the soviets’