Owen Walsh of the Leeds Marxists reviews Soy Cuba, a 1964 film written by Enrique Pineda Barnet and Yevgeny Yevtushenko and directed by Mikhail Kalatazov, which is a living monument to the Cuban Revolution. At a time when the future of the Cuban planned economy lies in the balance, this classic film is a must see for all who defend the Cuban Revolution.

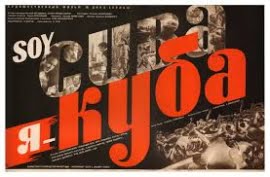

Soy Cuba is a 1964 film written by Enrique Pineda Barnet and Yevgeny Yevtushenko and directed by Mikhail Kalatazov. Among the most famous Spanish-language films ever, and considered to be the greatest Cuban film, it is regularly included in lists of the greatest films ever made, including popular lists by the likes of Empire magazine and expert polls by Sight and Sound. Among its fans are such names as Paul Greengrass, the leftist director of the Bourne trilogy, and Martin Scorsese, an interview with whom is featured in the latest DVD release of Soy Cuba by the independent label Mr Bongo.

The film seemingly spans the period immediately preceding the Cuban Revolution, and stretches into the revolutionary war itself. Divided into separate stories focusing on different characters who, with the narrator’s repeated phrase ‘soy Cuba’ (‘I am Cuba’), become windows into the Cuban nation, the film effectively depicts the real conditions of life for Cubans under the simultaneous and symbiotic dictatorships of Fulgencio Batista and imperialist Capital.

It has been described as a propaganda film by some, but this is a broadly inadequate designation. While propaganda cannot be sneered at by revolutionaries, it necessarily is by artists, and no justifiable attempt can be made against this film’s artistry – though some can against its politics.

A living monument to the Cuban Revolution, watching or re-watching ‘Soy Cuba’ is a highly recommended activity for all revolutionaries seriously interested in defending the Revolution in this time of both great victory and great peril for the Cuban people. With the announcement by Barack Obama of a thawing in relations between the two governments, the Cuban people have on one hand been vindicated in their glorious struggle to defy the imperialist master who ruled them so brutally for so long; but on the other, they now face the prospect of having their Revolution suffocated by cheap American goods and betrayed by those in the Cuban leadership who believe that the way forward lies in the forces of the market.

Who is Cuba?

The narrative of ‘Soy Cuba’ is not a typical one. As an exploration of the Cuban nation, the film is fragmented into various stories of the different classes and layers of the Cuban population. This includes: American occupiers (capitalists and sailors); Cuban prostitutes and poor traders; campesinos (peasants); and revolutionary students. Together, the stories of these people build a fragmentary but essentially united narrative of the Cuban nation.

While this narrative is necessarily nationalistic, its focal point is the Revolution, with the initial pain of daily exploitation and poverty gradually giving way to a defiant revolutionary cry in opposition to the prevailing conditions on the island. It is this collective action which unites the various personal stories into a political whole. It is a development which is given memorable expression in the eventual reply of the revolutionary radio station Radio Rebelde to the repeated cries of Cuban peasants. Hitherto echoing in the Cuban landscape without either a response or any political content, these cries are eventually translated into the language of the Revolution – the language of liberty and land.

Notable by their absence across the fragmented narrative, however, is the small Cuban working class. Those sections of the film concerned with the urban environment focus on the poor Cuban petit-bourgeoisie, lumpenproletariat and the revolutionary middle-class students. Only very small glimpses are given of the working class which, throughout the history of Marxism, is understood to be the necessary agent of revolutionary change. Here is one instance of the political limitations of the film. These political limitations are wholly consistent with the political limitations of the Revolution itself, making all the more perfect the unity between ‘Soy Cuba’ and the Revolution that provides the content and shapes the form of the film.

Traces of Stalinisim

Made at the height of the Cold War by a collaboration of Cuban and Soviet artists, the film bears traces of Stalinism in various ways. Its focus on the nation, while understandable given the national focus of any anti-imperialist struggle in the first instance, nevertheless fails to gesture beyond national boundaries. The revolution in ‘Soy Cuba’ and the socialism it hints at are not international, but based on the heroics of a single people – seemingly without a working class. Etched onto the film’s political vision, then, is Stalin’s theoretical excuse for counter-revolution – ‘socialism in one country’ – and the mistaken focus of the Cuban leadership on the peasantry.

Furthermore this Stalinism, and the logic of Cold War politics, can be sensed in the film’s depiction of American characters. While hostility to the exploitative American bourgeois – who used Cuba as a source of ‘exotic’ titillation for decades – is completely healthy, and opposition to the American military occupation of Guantanamo is similarly essential from a socialist perspective, the manner that the film-makers choose to illustrate these points suggests a lazy anti-Americanism. Particularly, the depiction of American sailors as sinister occupiers ready to deflower the beautiful image of Cuban female virginity is problematic. It substitutes nationalism for working class internationalism – and employs a tired, gendered trope to ostensibly revolutionary ends.

Taken in isolation, these political flaws could be excused as accidental or incidental. Taken together, though, they hint at the fatal flaws which have allowed the Cuban Revolution to develop in the way that it has. Lacking a tradition of working class democracy, but forced into a position of anti-imperialism by the intransigent defence of American capital by successive US governments, the revolutionary Cuban government is characterised by Marxists as a deformed workers’ state.

While socialistic in its economic forms (the nationalised planned economy), Cuba cannot be seriously described as socialist given the absence of a workers’ democracy and the general low level of production there. This is not to deny or diminish the incredible gains of the Revolution in areas such as agriculture, healthcare and education, but it is only in identifying such fundamental problems in the Revolution that it can be saved from utter destruction by the profit-hungry imperialists of America and Europe, and their allies on the right-wing of the Communist Party bureaucracy.

A revolutionary film

The film’s political flaws do not fundamentally change its character, though. And the character of ‘Soy Cuba’ is stridently political; it is anti-imperialist and revolutionary. This revolutionary spirit actually marks the film’s greatest artistic and technical achievement: its camerawork.

Famed in cinema history as an utterly remarkable example of the use of tracking shots, ‘Soy Cuba’ is technically stunning. The tracking shot is a supremely powerful tool in the kit of any film-maker and has been used most notably by Martin Scorcese (very famously in ‘Goodfellas’) and more recently in Joe Wright’s film ‘Atonement’. Never has it been used as powerfully, though, as in Kalatazov’s masterpiece.

While many films make of their camera a tool for offering a detached and ‘objective’ perspective on the action, or a vehicle for intimate, psychological studies, Kalatazov’s camera is one with the revolutionary people. Through his camera, Kalatazov reveals his partisanship, and directs the viewer’s sympathy in no uncertain terms. Whether intimately moving with a sex worker as she laments her brutalised position and the entry of American exploitation into her home, or crazily getting lost in the fields of sugar cane as a desperate and angry campesino expresses his political impotence in (literally) fruitless violence, the camera in ‘Soy Cuba’ is unashamedly an instrument of revolution.

In this way, ‘Soy Cuba’ is an exemplary demonstration of how social revolution provides all kinds of innovatory and liberating possibilities to artists. While these connections cannot be regarded simple-mindedly – the immanent chaos of revolution is not conducive to technical innovation, whether in production, science or culture – it is only through social revolution that humanity can effectively build a new culture, which will necessarily be linked to a new experience of life. Socialist revolution is also the only way to liberate art from the crushing pressures of commodity production, which is the basis for all kinds of artistic bankruptcy under capitalism.

Equally, and somewhat ironically given the film’s flawless reflection of Stalinist politics, for a healthy development of culture it must be free of bureaucratic control. While anti-Communists label the film propaganda, there were concerns upon its release in the Soviet Union that it was not sufficiently ‘revolutionary’ – that is, that it did not adequately prostrate its artistic values before the political demands of the counter-revolutionary Stalinist bureaucracy. Therefore, the history of the film is itself an example of the backward role played by the Stalinised Communist Party, whose politics it nevertheless reflects.

But in spite of Stalinist philistinism, ‘Soy Cuba’ stands alongside the avant-garde Soviet films of Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov in its revolutionary and artistic power. It ought to be regarded as a canonical example of revolutionary film-making, as well as a text from which honest defenders of the Cuban Revolution can learn the lessons of the past.

For a free Cuban art, we need a free Cuban people – no to capitalist restoration; forward to workers’ democracy and international socialism! Cuba libre!