In the autumn of 1916 the Industrial Workers of the World, better known as the Wobblies, were trying to organise lumber workers near Everett, Washington in the USA. A series of attempts to organise by the workers had lead to a murderous response from the employers. IWW organisers were picked up, beaten and deported but kept coming back and trying again. One of their number, Wesley Everest was dragged out of jail by a mob, battered, castrated and hung from a bridge.

The Wobblies decided to stage a meeting in Everett on 5th of November and to avoid being picked off one by one, arrived together by boat. They arrived singing the well-known Wobbly songs and in particular ‘Hold the Fort’. They were met by an army of armed police and deputised thugs. These gunmen opened fire when the Wobblies attempted to land. Five men were killed plus seven others whose bodies were never found and many more wounded. When the Verona returned to Seattle the survivors were arrested and they were charged with murder.

The IWW set up a defence campaign and appointed Charles Ashleigh to run it. Charles, whom I knew personally in my YCL days in Brighton, was a poet of the IWW. He gave the oration at the funeral of the Everett martyrs and penned the poem, ‘Everett, November Fifth’.

The poem goes as follows:

Song on his lips, he came;

Song on his lips, he came;

Song on his lips, he went;

This be the token we bear of him,

Soldier of Discontent!

Out of the dark they came; out of the night

Of poverty and injury and woe,

With flaming hope, their vision thrilled to light,

Song on their lips, and every heart aglow;

They came, that none should trample Labor’s right

To speak, and voice her centuries of pain.

Bare hands against the masters armoured might!

A dream to match the tools of sordid gain!

And then the decks went red; and the grey sea

Was written crimsonly with ebbing life.

The barricade spewed shots and mockery

And curses, and the drunken lust of strife.

Yet, the mad chorus from that devil’s host,-

Yes, all the tumult of that butcher throng,

Compound of bullets, booze and coward boast,

Could not out-shriek one dying worker’s song!

Song on his lips, he came;

Song on his lips, he went;

This be the token we bear of him,

Soldier of Discontent!

Charles was born in Britain and lived in London and Brighton where he went to the Grammar School. He joined the Independent Labour Party when only fifteen years old. He worked with the Clarion Scouts and in 1908 was sent to South Wales as an agitator for the Labour Party. According to Steve Kellerman’s introduction to Charles book (see below) "During Ashleigh’s stay in Wales he became one of the leading figures in a land occupation…

At a time of high unemployment, a group of out-of-work agricultural labourers seized a parcel of land called Leckwith Common near Cardiff, which had once been common land but had been enclosed by the noble Bute family and was then lying idle.

Squatters… erected housing for themselves and began to work the land… Eventually the settlers were driven off by the police but the incident had garnered widespread publicity for the plight of the unemployed… It also appealed strongly to Ashleigh’s predisposition towards direct action."

He certainly very soon became involved in direct action when he arrived in the USA in 1912. He had jumped ship in Oregon, crossed into Canada and then back into Washington State to officially enter the USA. Charles initially joined the Socialist Party of America but soon left it to join the IWW. He believed that the IWW idea of replacing capitalism with workers ownership and control of society through ‘one big union’ was the way ahead.

Charles became a full-time agitator with the IWW. As Kellerman says, the pay of such an agitator covered, ‘little more than food and tobacco expenses. The organisers lived at a standard similar to that of the hobos they sought to influence…..and dining in the same skid row cafes.’

The IWW took up a position in opposition to the 1914-1918 World War. They were, in 1917 made the scapegoats for the government’s attacks on the anti-war movement. In September of that year 184 wobbly activists were rounded up and arraigned in 1918 in trials in Chicago and other cities. Charles Ashleigh was put on trial with 100 other men in Chicago. It was during this trial that the black wobbly Ben Fletcher said, "Judge Landis has been using bad English today- his sentences are too long." Brutal sentences were handed down at the end of a farce of a trial. The IWW won the argument but the state had the power and put them away.

Bolsheviks

There had been many debates in the IWW over the years about how to beat capitalism. Many still thought if you could get all the workers in one big union the fight would be won. This still didn’t answer the question of how to bring the workers to power and how to take over. The victory of the Bolsheviks in Russia in 1917 had a huge impact on large sections of the Wobblies. Ashleigh, like many leading Wobblies such as Bill Haywood and James Cannon took the lesson from the October Revolution, that to win power for the workers a revolutionary party was needed and they became Communists.

On his release from prison Charles was deported to Britain where he became active in the Communist Party of Great Britain. He worked for many years in Berlin and Moscow for the Profintern (The Red International of Trade Unions). Kellermans review says Charles remained a member of the CPGB for the rest of his life. Well, by Charles account that is only just true! In the thirties in Moscow he ran into difficulties with the apparatchiks. He was too much of a free spirit for them. Apparently he was openly homosexual although I was blissfully unaware of that when I knew him.

They kicked him out of Moscow and according to Charles demanded his expulsion from the CPGB. It seems that Harry Pollit, then leader of the CPGB ‘took care’ of Charles’ Party Card until ‘better times’ post 1956? Charles was interviewed for the Sussex Society for the Study of Labour History in 1973 and it would be interesting to know what he told them!

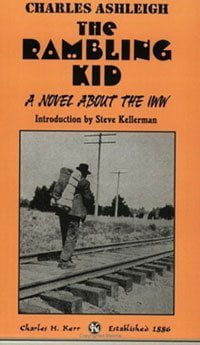

In 1930 Charles wrote ‘The Rambling Kid’, A Novel about the IWW. It has been republished by the Charles H Kerr Publishing Company of Chicago with an introduction by Steve Kellerman.

In 1930 Charles wrote ‘The Rambling Kid’, A Novel about the IWW. It has been republished by the Charles H Kerr Publishing Company of Chicago with an introduction by Steve Kellerman.

Some people have said it is an autobiography. I think not, although the character of the heroes close friend Elsie is interesting from that view. "Elsie was a tall, handsome youth, the son of middle-class parents in St. Paul… His somewhat languid unhurried air, and his refined pronunciation, had earned him the feminine nickname."

I lost touch with Charles when I left Brighton. Kellerman says he died in isolation in Brighton in 1974. I am sorry for that.

I started out here meaning to write a review of ‘Rambling Kid’ but have rambled on about the author. The book is an adventure story, a damn good read. Get it and read it for yourself.