Today, 7 November, marks the 105th anniversary of the Russian Revolution – an event which altered the entire course of human history.

For the first time – if we exclude the brief but glorious episode of the Paris Commune – the working class took power into their own hands and began the gigantic task of the socialist reconstruction of society.

To celebrate these inspiring events, we are republishing an abridged version of an article by Alan Woods from 1992, recently printed in the latest issue of Socialist Appeal, which gives an excellent overview of the revolution and its main lessons for today.

Click here to read the full version of this article. And visit our special website In Defence of October for a huge collection of articles, videos, and other material analysing the 1917 Russian Revolution.

“The October revolution laid the foundation of a new culture, taking everybody into consideration, and for that very reason immediately acquiring international significance. Even supposing for a moment that owing to unfavourable circumstances and hostile blows the Soviet regime should be temporarily overthrown, the inexpungable imprint of the October revolution would nevertheless remain upon the whole future development of mankind.” – Leon Trotsky, The History of the Russian Revolution

In order to justify the capitalist system, it is necessary to show that revolution is a bad thing, that it represents a horrible deviation from the ‘norms’ of peaceful social evolution, which inevitably ends in disaster.

Yet revolutions happen, and not by accident. A revolution becomes inevitable when a particular form of society enters into conflict with the development of the productive forces, which forms the basis of all human progress.

In an effort to discredit the October Revolution, the ruling class, through the agency of its hired hacks in the universities, has assiduously cultivated the myth that the Bolshevik Revolution was only a ‘coup d’etat’ pulled off by Lenin and a handful of conspirators.

In reality, as Trotsky explains, the essence of a revolution is the direct intervention of the masses in the life of society and politics. In ‘normal’ periods, the majority of people are content to leave the running of society in the hands of the ‘experts’ – the parliamentarians, councillors, lawyers, journalists, trade union officials, university professors, and the rest of them.

View this post on Instagram

Wars and revolutions

The human mind, in general, is not revolutionary, but conservative. Consciousness tends to lag far behind the changes which occur in the objective world of the economy and society.

Only in the last resort, when there is no alternative, do the majority opt for a decisive break with the existing order. Long before this, they will try by every means to adapt, to compromise, to seek the imagined ‘line of least resistance’.

The October Revolution was the product of the entire preceding period. Before finally opting for the Bolsheviks, the Russian workers and peasants had already passed through the experience of two revolutions (1905 and February 1917) and two wars (1904-5 and 1914-17).

Tsarist Russia was an economically backward capitalist power. Large-scale industry was established in a handful of centres as a result of Western investment. However, the vast majority of the population were peasants, sunk in conditions of almost mediaeval backwardness.

The stormy growth of industry in the early years of the twentieth century led to a rapid growth of the working class. Unlike Britain, where capitalism experienced a slow, gradual, organic growth for 200 years, the development of capitalism in Russia was telescoped into a couple of decades.

As a result, Russian industry did not have to pass through the phase of handicrafts, small cottage industry, through manufacture to large-scale enterprises. Huge factories were established with the most modern techniques imported from Britain, Germany and the USA. Along with the most modern technology imported from the West, came the most modern and advanced ideas of socialism.

From the 1890s onwards, Marxism succeeded in displacing the old terrorist and utopian socialist trend of Narodnism as the dominant tendency in the workers’ movement.

First World War

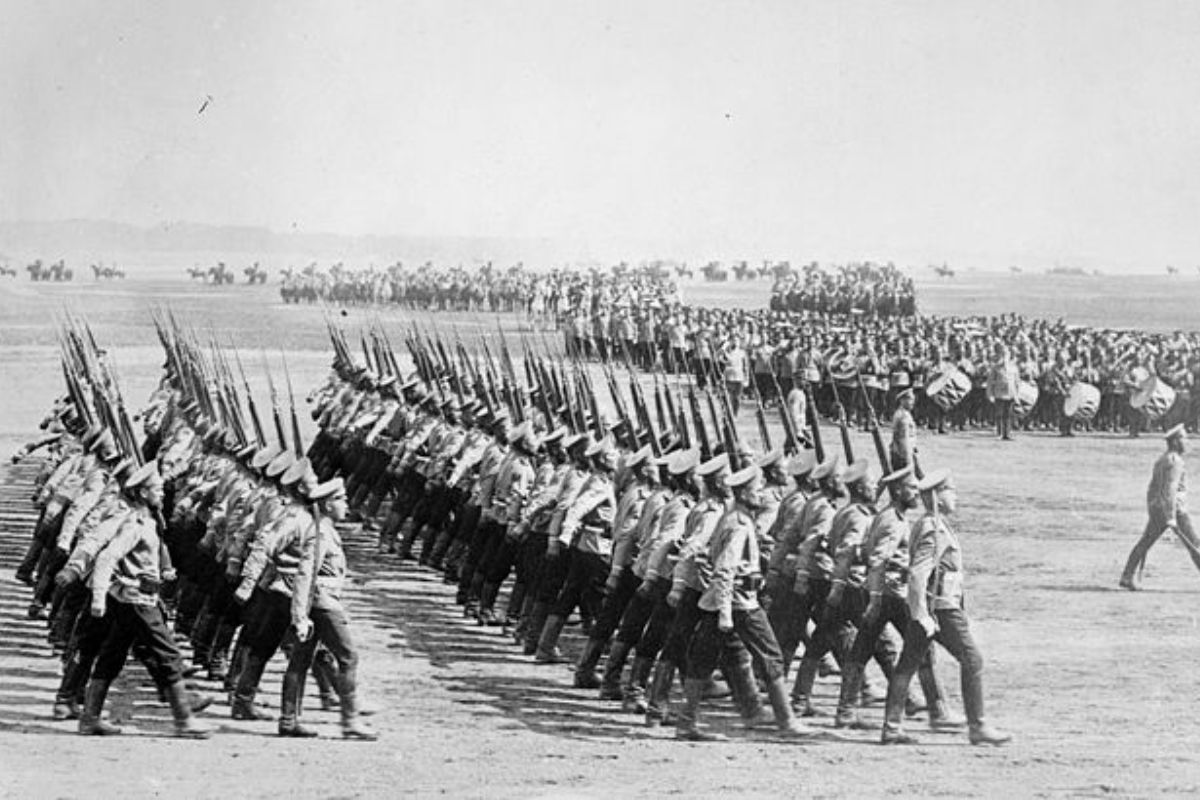

On the eve of the First World War, Russia stood once more on the brink of revolution. It is possible that the Bolsheviks could have come to power then, but the situation was cut across by the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914.

During the war, the Bolshevik party was decimated by arrests and exile. The youth, which was the party’s main avenue of recruitment, was conscripted into the army, where the worker element was scattered in a sea of backward peasant soldiers.

In exile, Lenin was in contact with maybe a couple of dozen collaborators. In 1915, at the conference of socialist internationalists in Zimmerwald, Lenin joked that you could put all the internationalists in the world into four stage-coaches.

At a meeting of Swiss young socialists in January 1917, Lenin said that he probably would not live to see the socialist revolution. Within a few weeks, the Tsar had been overthrown, and by the end of the year, Lenin was at the head of the first workers’ government in the world.

How did this extraordinary transformation take place?

The February revolution

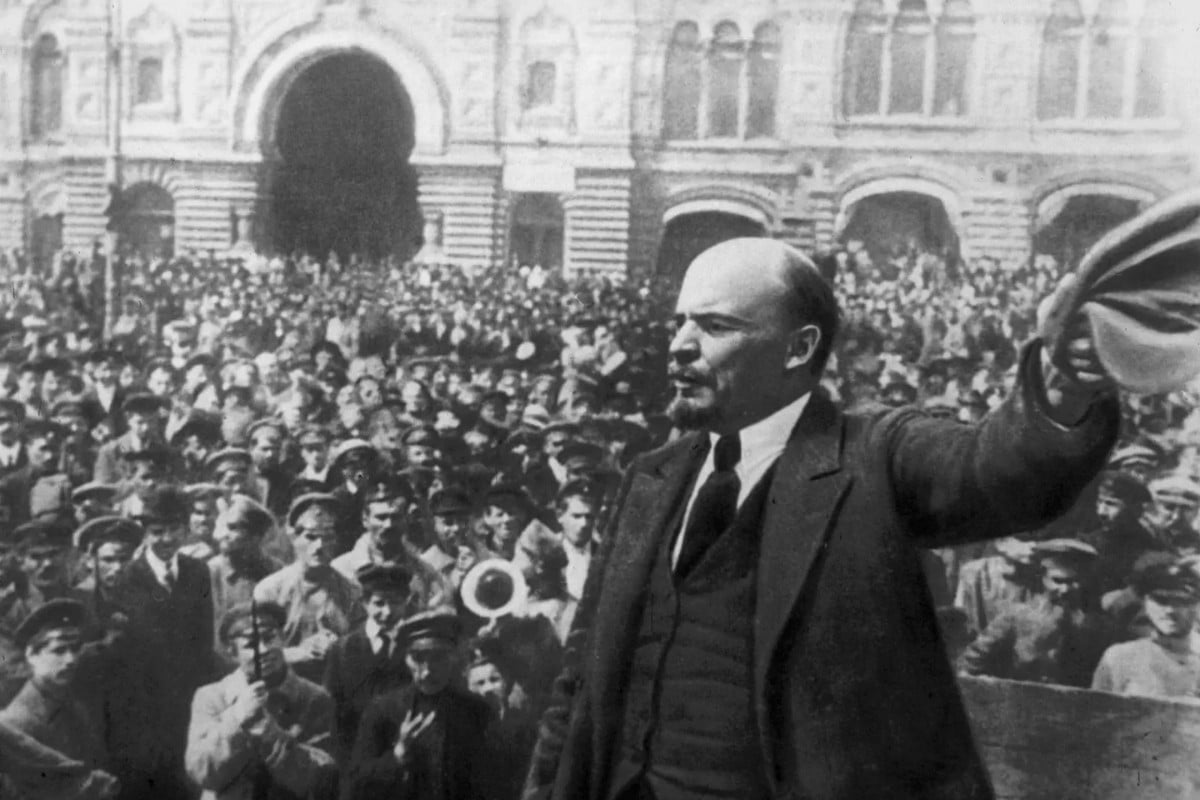

The revolution began with a strike movement in Petrograd that assumed sweeping proportions at the start of 1917. The mood of discontent emanating from the industrial centres found an echo in the ranks of the army, suffering from defeat and exhaustion.

Despite all its armed might, Tsarism fell at the first serious challenge. The army collapsed like a house of cards, once the workers confronted it with a manifest determination to change society.

The working class as a whole learns from experience – especially the experience of great events. The experience of 1905, despite the defeat, had left an indelible impression which immediately re-emerged in February with the creation of the Soviets – elected committees of workers and soldiers – which were at the same time organs of struggle and, potentially, organs of a new power.

Mensheviks

As has happened many times in history, in the February Revolution, the workers had the power in their hands, but did not recognise the fact. With correct leadership, the working class could have immediately carried out the socialist revolution. But under the leadership of the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries, the February revolution ended in the abortion of ‘dual power’.

Inevitably, in the first instance, the masses seek the line of least resistance, the easiest solutions, the well-known political figures, and the familiar political parties.

In the February revolution, the entire balance of class forces was changed by the explosive emergence on the scene of the mass of politically untutored workers, who tended to back the Mensheviks.

The decisive element in the equation was the army, and here the peasants had a crushing preponderance. The peasant soldiers, recently awakened to political life, looked, not to the Bolsheviks, but to the ‘moderate’ socialist leaders the Mensheviks and especially the Social Revolutionaries.

The masses placed their trust in the reformist labour leaders. And the latter, as always, placed their trust in the ‘liberal’ wing of the bourgeoisie, which in turn, was desperately striving to defend the monarchy and put an end to the revolution.

The Provisional Government

The Provisional Government which emerged from the February Revolution was a government of landlords and capitalists calling themselves ‘democrats’, despite the fact that they were brought to power by a mass movement of workers and soldiers.

The worker activists were deeply distrustful of the government. But among the mass of society there was a wave of euphoria. The masses had illusions in their leaders.

The prevailing atmosphere of revolutionary democratic intoxication even affected some of the Bolshevik leaders in Petrograd. Lenin was still in exile in Switzerland. The main leaders in Petrograd were Kamenev and Stalin, who succumbed to the pressure for ‘unity’ and supported the bourgeois Provisional Government.

Lenin was implacably opposed to this opportunist line, and after his return in April, the tension between Lenin and the majority of the leaders was so great that Lenin was compelled to publish his April Theses in Pravda under his own signature.

Lenin explained that the revolution had not achieved its central objectives: that it was necessary to overthrow the Provisional Government; that the workers must take power, allied with the mass of poor peasants. Only by these means could the war be ended, the land be given to the peasants and the conditions established for a transition to a socialist regime.

In essence, these ideas were identical to the perspectives brilliantly worked out by Trotsky in 1904-5, and known to history as the ‘permanent revolution’.

‘Patiently explain’

Lenin’s ideas won the day. However, the Bolsheviks remained a minority in the Soviets, and the Soviet leaders – the SRs and Mensheviks – were backing the Provisional Government.

And here we see the flexible tactics of Lenin, far removed from ultra-left adventurism. Under the slogan: ‘patiently explain’, he urged the Bolsheviks to face the Soviet workers to put demands on the reformist leaders, to demand action instead of words, to publish the secret treaties, to end the war, to break with the bourgeoisie and take power into their own hands.

If they did these things, Lenin repeated many times, then the struggle for power would be reduced to the peaceful struggle for a majority in the Soviets.

However, the Mensheviks and SR leaders had no intention of breaking with the bourgeois Provisional Government. In reality, they were terrified of taking power and were more afraid of the workers and peasants than the counter-revolutionary general staff.

The failure of the bourgeois Provisional Government to solve a single one of the basic problems of society provoked a sharp reaction in the main working-class centres, especially Petrograd.

The constant increase in prices and the cut in the bread ration caused a ferment of discontent. Above all, the continuation of the war raised the temperature to boiling point.

The workers reacted with a series of mass demonstrations starting in April, which indicated an ever-increasing shift to the left in the mood of the workers.

The apologists for the ruling class always seek to present revolution as a bloodthirsty event. But history demonstrates the falsity of this.

The bloodiest pages in the history of social strife occur when a cowardly and inept leadership vacillates at the decisive moment and fails to put an end to the crisis of society by vigorous action. The initiative then passes to the forces of counter-revolution which are invariably merciless, and prepared to wade through rivers of blood to ‘teach the masses a lesson’.

In April 1917, the reformist leaders of the Soviets could have taken power ‘peacefully’ – as Lenin invited them to do. There would have been no civil war. The authority of these leaders was such that the workers and soldiers would have obeyed them unconditionally. The reactionaries would have been generals without an army.

But the refusal of the reformists to take power peacefully made bloodshed and violence inevitable, and put the gains of the revolution in jeopardy. Instead of taking power, the Menshevik and SR leaders entered the first coalition government with the bourgeois leaders.

These same ‘socialists’ who had held a pacifist position earlier, once they crossed the threshold of the ministry, instantly and enthusiastically backed the war. A new offensive was announced. Measures to re-introduce discipline in the army reflected an attempt to re-assert the power of the officer caste. The mood of the workers in Petrograd was near boiling point.

Growth of consciousness

The workers and soldiers came to a demonstration called by the Mensheviks in July carrying ‘placards with the slogans of the Bolsheviks: ‘Down with the secret treaties!’, “Down with the ten capitalist ministers!’, ‘No to the offensive!’, ‘All Power to the Soviets!’.

Infuriated by the new military offensive, the most radical sections of the Petrograd garrison were preparing for an armed demonstration. Realising that the provinces were not as radicalised and not yet ready for a showdown with the Provisional Government, the Bolsheviks tried to restrain the soldiers, but eventually were compelled to put themselves at the head of the demonstration in order to prevent a massacre.

As the Bolsheviks had warned, the government seized on the opportunity to crack down on the movement, leaning on more backward regiments. The ‘July Days’ ended in a defeat, but thanks to the responsible leadership of the Bolsheviks, the losses were kept to a minimum, and the effects of the defeat were not long-lasting.

A revolution is not a one-act drama. Neither is it a simple, forward-moving process. The Russian revolution unfolded over nine months. The Spanish revolution took place over seven years. Within the revolution, there are periods of breathtaking advance, but also periods of lull, of defeat, and even of reaction.

Counter-revolution

From February onwards, the counter-revolution had been biding its time, hiding behind the coattails of the Provisional Government. The offensive, and the crushing of the Bolsheviks in July, now tilted the pendulum to the right.

The officer caste began serious preparations for a coup d’etat, culminating in General Kornilov’s uprising at the end of August. Only the courageous reaction of the workers and soldiers saved the revolution.

The railway workers, risking their lives, refused to drive the trains, or misdirected them. Kornilov’s army found itself without supplies, without petrol, disorganised and disoriented.

Agitators, mainly Bolsheviks, got to work among Kornilov’s troops and won them over. Kornilov ended up a general without an army. Reluctantly, the Mensheviks and SRs were forced to legalise the Bolsheviks to help them defeat Kornilov.

Soviets

The position of the Bolsheviks now became decisive in the Petrograd Soviet. Moreover, the time was growing near for the second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, at which the Bolsheviks were assured of a majority.

One of the most blatant lies about October is that the Bolsheviks were ‘undemocratic’ because they based themselves on Soviet democracy rather than a parliament (‘Constituent Assembly’).

The truth is very different. The Soviet system in 1917 and the years immediately following the revolution was the most democratic system of representation of the people ever known.

The Soviets were born in 1905 as extended strike committees. Representatives to the soviets were elected directly by their workmates and instantly recallable.

Compare this to the present system in Britain, where there is no means of recall. Once a parliament is elected, it cannot be removed until the next general election. Governments are free to renege on their promises – and invariably do so.

Most parliamentarians are professional politicians, with no contact with the people who elected them. They live in another world.

In a revolutionary situation, where the moods of the masses change rapidly, the cumbersome mechanisms of formal bourgeois democracy would be utterly incapable of reflecting accurately the situation.

Bolshevik majority

By October, the Bolsheviks had a clear majority in the Soviets.

A point is reached in every revolution where the question of power is posed point-blank. At this stage, either the revolutionary class goes over to a decisive offensive, or the opportunity is lost, and may not return for a long time.

The masses cannot be kept forever in a state of agitation. If the chance is lost, and the initiative passes to the counter-revolution, then bloodshed, civil-war and reaction will inevitably follow.

Such is the importance of leadership that, ultimately, the fate of the Russian revolution was determined by two men – Lenin and Trotsky. The other leaders of the Bolsheviks – Stalin, Kamenev, Zinoviev – repeatedly vacillated under the pressure of middle-class ‘public opinion’.

Thanks mainly to the work of Trotsky, the Petrograd garrison was won over to the Bolshevik cause.

Trotsky made use of the Military Revolutionary Committee, set up by the reformist-led executive of the Soviet, to arm the workers in defence against the reactionaries. The workers in the arms factories distributed rifles to the Red Guard. Mass meetings, demonstrations and even military parades were held openly on the streets of Petrograd.

Far from being the work of a tiny, secret group of conspirators, the preparations for the insurrection involved a massive participation by workers and soldiers.

John Reed, in his celebrated book Ten Days that Shook the World gives a graphic eye-witness account of these mass meetings, which were held at all hours of the day and night, addressed by Bolsheviks, left SRs, soldiers who recently arrived from the front, and even anarchists.

All spoke with one voice: ‘Down with Kerensky’s government!’, ‘Down with the war!’, ‘All power to the Soviets!’.

Revolutionary Petrograd

The actual seizure of power took place smoothly, and with very little resistance. The workers, soldiers and sailors occupied one government building after another, without firing a shot. How was this possible?

Only a few months earlier, the position of Kerensky and the Provisional Government appeared to be unassailable. But in the moment of truth, it found no defenders. Its authority had collapsed. The masses deserted it and moved over to the Bolsheviks.

The very idea that all this was the result of a clever conspiracy by a tiny group is worthy of a police mentality.

The overwhelming victory of the Bolsheviks at the Soviet Congress underlines the fact that the right-wing reformist leaders had lost all their support. The Mensheviks and SRs won only one-tenth of the Congress – about 60 people in all. The Soviets voted by a massive majority for the assumption of power.

On the day of taking power, the Congress of Soviets adopted its first appeal: “To the Workers, Soldiers, and Peasants!” This announced the overthrow of the Provisional Government and decreed that all power in the localities should pass to the Soviets of Workers, Soldiers and Peasant Deputies.

The appeal summarised in one simple paragraph the programme of the Bolsheviks:

“The Soviet government will propose an immediate democratic peace to all the nations and an immediate armistice on all fronts. It will secure the transfer of the land of the landed proprietors, the crown and the monasteries to the peasant committees without compensation; it will protect the rights of the soldiers by introducing complete democracy in the army; it will establish workers’ control over production; it will guarantee all the nations inhabiting Russia the genuine right to self-determination.”