The October Revolution of 1917 brought about the greatest advance of the productive forces of any country in history. Before the Revolution, tsarist Russia was an extremely backward, semi-feudal economy with a predominantly illiterate population. Out of a total population of 150 million people there were only approximately four million industrial workers.

Under frightful conditions of economic, social and cultural backwardness, the regime of workers’ democracy established by Lenin and Trotsky began the titanic task of dragging Russia out of backwardness on the basis of a nationalised planned economy. The results have no precedent in economic history. Within the space of two decades Russia had established a powerful industrial base, developed industry, science and technology and abolished illiteracy. It achieved remarkable advances in the fields of health, culture and education. This was at a time when the Western world was in the grip of mass unemployment and economic collapse in the Great Depression.

In a period of 50 years, the USSR increased its gross domestic product nine times over. By the late 1970s, the Soviet Union was a formidable industrial power, which in absolute terms had already overtaken the rest of the world in a whole series of key sectors. The USSR was the world’s second biggest industrial producer after the USA and was the biggest producer of oil, steel, cement, tractors and many machine tools.

Nor is the full extent of the achievement expressed in these figures. All this was achieved virtually without unemployment or inflation. Unemployment like that in the West was unknown in the Soviet Union. In fact, it was legally a crime. (Ironically, this law still remains on the statute books today, although it means nothing.) There might be examples of cases arising from bungling or individuals who came into conflict with the authorities being deprived of their jobs, but such phenomena did not flow from the nature of a nationalised planned economy, and need not have existed. They had nothing in common with either the cyclical unemployment of capitalism or the organic cancer which now affects the whole of the Western world and which currently condemns 35 million people in the OECD countries to a life of enforced idleness.

Moreover, for most of the post-war period, there was little or no inflation. The bureaucracy learned the truth of Trotsky’s warning that “inflation is the syphilis of a planned economy.” After the Second World War, for the most part, they took care to ensure that inflation was kept under control. This was particularly the case with the price of basic items of consumption. Before perestroika (reconstruction), the last time meat and dairy prices had been increased was in 1962. Bread, sugar and most food prices had last been increased in 1955. Rents were extremely low, particularly when compared to the West, where most workers have to pay a third or more of their wages on housing costs. Only in the last period, with the chaos of perestroika, did this begin to break down. With the rush towards a market economy, both unemployment and inflation soared to unprecedented levels.

The USSR had a balanced budget and even generated a small surplus every year. It is interesting to note that not a single Western government has succeeded in achieving this result, just as they have not succeeded in achieving full employment and zero inflation, things which also existed in the Soviet Union. The Western critics of the Soviet Union kept very quiet about this, because it demonstrated the possibilities of even a transitional economy, never mind socialism.

From feudalism to space

From a backward, semi-feudal, mainly illiterate country in 1917, the USSR became a modern, developed economy, with a quarter of the world’s scientists, a health and educational system equal or superior to anything found in the West, able to launch the first space satellite and put the first man into space. In the 1980s, the USSR had more scientists than the USA, Japan, Britain and Germany combined. Only recently was the West compelled to admit grudgingly that the Soviet space programme was far in advance of America’s.

Yet, despite these extraordinary successes, the USSR collapsed. The question that must be addressed is why this occurred. The explanations of the capitalist ‘experts’ are as predictable, as they are hollow. Socialism (or communism) failed. End of story. But the commentaries of the Labour leaders, both left and right, are not much better. The right-wing reformists, as always, merely echo the views of the ruling class. From the left reformists, we get an embarrassed silence. The leaders of the Communist Parties in the West, who yesterday uncritically supported all the crimes of Stalinism, now try to distance themselves from a discredited regime but have no answer to the questions of the workers and youth, who demand serious explanations.

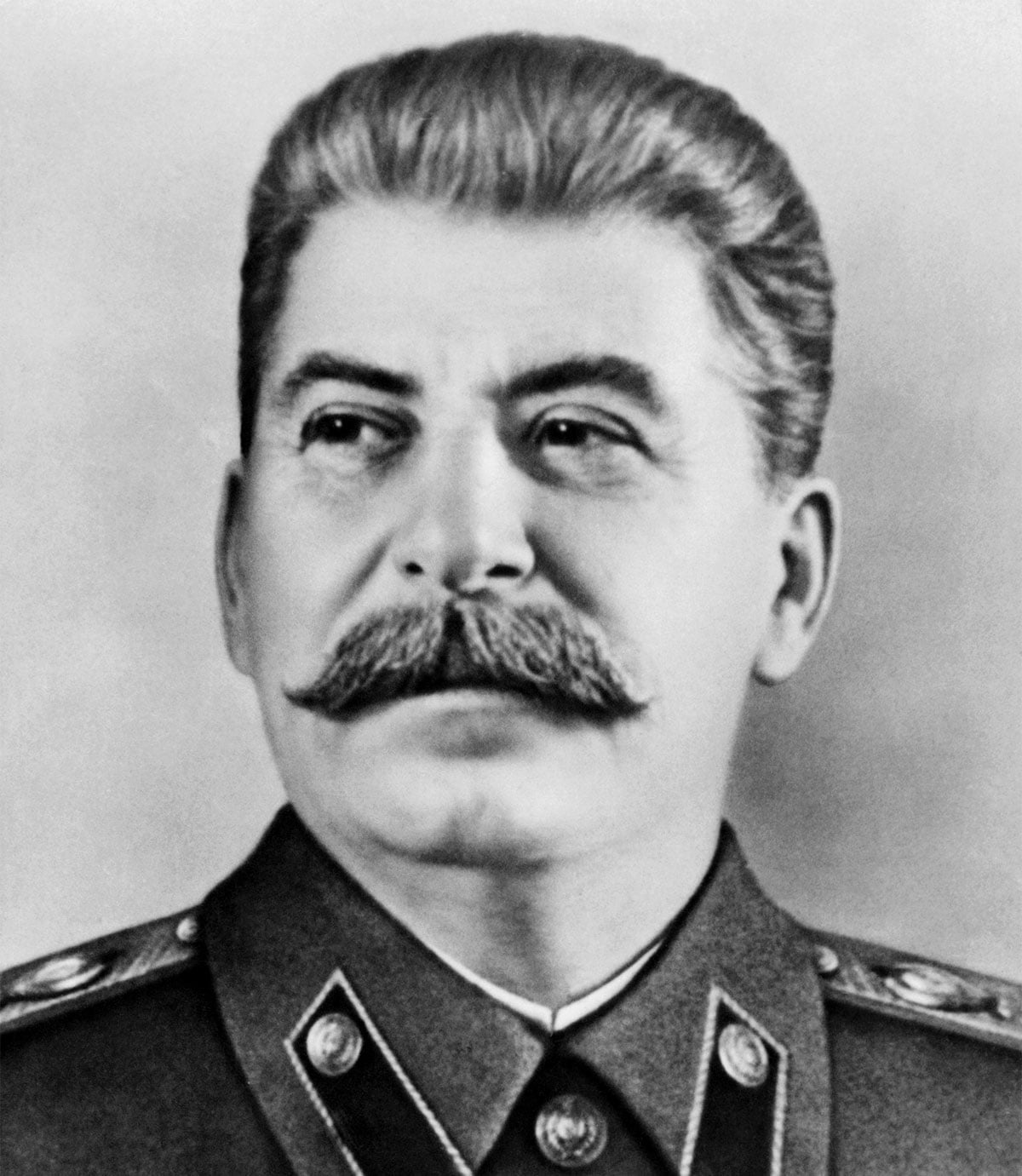

The achievements of Soviet industry, science and technology have already been explained but there was another side to the picture. The democratic workers’ state established by Lenin and Trotsky was replaced by the monstrously deformed bureaucratic state of Stalin. This was a terrible regression, signifying the liquidation of the political power of the working class but not of the fundamental socio-economic conquests of October. The new property relations, which had their clearest expression in the nationalised planned economy, remained.

In the 1920s Trotsky wrote a small book called ‘Towards socialism or capitalism?’ That was always the decisive question for the USSR. The official propaganda was that the Soviet Union was moving inexorably towards the achievement of socialism. In the 1960s Khrushchev boasted that socialism had already been achieved and the USSR was going to build a fully communist society in twenty years. But the truth was that the Soviet Union was moving in another direction altogether.

A movement towards socialism should signify a gradual reduction in inequality but in the Soviet Union inequality continually increased. An abyss opened up between the masses and the millions of privileged officials and their wives and children, with their smart clothes, big cars, comfortable apartments and dachas. The contradiction was still more glaring because it contrasted with the official propaganda about socialism and communism.

From the standpoint of the masses, economic success cannot be reduced to the amount of steel, cement or electricity produced. Living standards depend above all on the production of commodities that are of good quality, cheap and easily available: clothes, shoes, food, washing machines, televisions and the like. But in those fields the USSR lagged far behind the West. That would not have been so serious but for the fact that some people enjoyed access to these things while most did not.

The Stalinist bureaucracy

The reason why Stalinism could last so long, despite all the crying contradictions it created, was precisely the fact that for decades the nationalised planned economy made extraordinary strides forward. But the suffocating rule of the bureaucracy resulted in corruption, mismanagement, bungling and waste on a colossal scale. It undermined the gains of the planned economy. To the degree that the USSR developed to a higher level, the negative effects of bureaucracy had even more damaging consequences.

The reason why Stalinism could last so long, despite all the crying contradictions it created, was precisely the fact that for decades the nationalised planned economy made extraordinary strides forward. But the suffocating rule of the bureaucracy resulted in corruption, mismanagement, bungling and waste on a colossal scale. It undermined the gains of the planned economy. To the degree that the USSR developed to a higher level, the negative effects of bureaucracy had even more damaging consequences.

The bureaucracy always acted as a brake on the development of the productive forces. But whereas the task of building up heavy industry was relatively simple, a modern sophisticated economy with its complex relations between heavy and light industry, science and technology cannot be run by bureaucratic fiat without causing the most serious disruption. The costs of maintaining high levels of military expenditure and the costs of maintaining its grip on Eastern Europe imposed further strains on the Soviet economy.

With all the colossal resources at its disposal, the powerful industrial base and the army of high-class technicians and scientists, the bureaucracy was unable to achieve the same results as the West. In the vital fields of productivity and living standards, the Soviet Union lagged behind. The main reason was the colossal burden imposed on the Soviet economy by the bureaucracy – the millions of greedy and corrupt officials that were running the Soviet Union without any control on the part of the working class.

As a result, the Soviet Union was falling behind the West. As long as the productive forces in the USSR continued to develop, the pro-capitalist tendency was insignificant. But the impasse of Stalinism transformed the situation completely. By the mid-1960s, the system of a bureaucratically controlled planned economy [had] reached its limits. Once the Soviet Union was not able to obtain better results than capitalism, its fate was sealed.

It was at this point that Ted [Grant] concluded that the fall of Stalinism was inevitable, a brilliant prediction that he made as early as 1972. From a Marxist point of view, such a perspective was inescapable. Marxism explains that in the final analysis the viability of a given socio-economic system depends on its ability to develop the productive forces. This book explains the whole process in great detail, and shows how, in the period after 1965, the growth rate of the Soviet economy began to slow down.

Between 1965 and 1970, the growth rate was 5.4 per cent. Over the next seven-year period, between 1971 and 1978, the average rate of growth was only 3.7 per cent. This compared to an average of 3.5 per cent for the advanced capitalist economies of the OECD. In other words, the growth rate of the Soviet Union was no longer much higher than that achieved under capitalism, a disastrous state of affairs. As a result, the USSR’s share of total world production actually fell slightly, from 12.5 per cent in 1960 to 12.3 per cent in 1979. In the same period, Japan increased its share from 4.7 per cent to 9.2 per cent. All Khrushchev’s talk about catching up with and overtaking America evaporated into thin air. The growth rate in the Soviet Union continued to fall until it was reduced to zero at the end of the Brezhnev period (the ‘period of stagnation’ as it was christened by Gorbachev).

Once this stage had been reached, the bureaucracy ceased to play even the relatively progressive role it had played in the past. This is the reason why the Soviet regime entered into crisis. Ted Grant was the only Marxist to draw the necessary conclusion from this. He explained that once the Soviet Union was unable to get better results than capitalism, the regime was doomed. By contrast, every other tendency, from the bourgeois to the Stalinists, took for granted that the apparently monolithic regimes in Russia, China and Eastern Europe would last almost indefinitely.

Political counter-revolution

The political counter-revolution carried out by the Stalinist bureaucracy in Russia completely liquidated the regime of workers’ Soviet democracy but did not destroy the new property relations established by the October Revolution. The ruling bureaucracy based itself on the nationalised, planned economy and played a relatively progressive role in developing the productive forces. However, they managed this at three times the cost of capitalism, with tremendous waste, corruption and mismanagement, which Trotsky had pointed out even before the war, when the economy was advancing at 20 per cent a year.

But despite its successes, Stalinism did not solve the problems of society. In reality, it represented a monstrous historical anomaly, the result of a peculiar historical concatenation of circumstances. The Soviet Union under Stalin was based on a fundamental contradiction. The nationalised planned economy was in contradiction to the bureaucratic state. Even in the period of the first five-year plans, the bureaucratic regime was responsible for colossal waste. This contradiction did not disappear with the development of the economy, but, on the contrary, grew ever more unbearable until eventually the system broke down completely.

This is now common knowledge. But to be wise after the event is relatively easy. It is not so easy to predict historical processes in advance, but this was certainly the case with Ted Grant’s remarkable writings on Russia, which accurately plotted the graph of the decline of Stalinism and predicted its outcome. Here alone we find a comprehensive analysis of the reasons for the crisis of the bureaucratic regime, which even today remains a book sealed with seven seals for all other commentators on events in the former USSR.

In defence of October

What failed in Russia and Eastern Europe was not communism or socialism, in any sense that this was understood by Marx or Lenin, but a bureaucratic and totalitarian caricature. Lenin explained that the movement towards socialism requires the democratic control of industry, society and the state by the proletariat. Genuine socialism is incompatible with the rule of a privileged bureaucratic elite, which will inevitably be accompanied by colossal corruption, nepotism, waste, mismanagement, and chaos.

What failed in Russia and Eastern Europe was not communism or socialism, in any sense that this was understood by Marx or Lenin, but a bureaucratic and totalitarian caricature. Lenin explained that the movement towards socialism requires the democratic control of industry, society and the state by the proletariat. Genuine socialism is incompatible with the rule of a privileged bureaucratic elite, which will inevitably be accompanied by colossal corruption, nepotism, waste, mismanagement, and chaos.

The nationalised planned economies in the USSR and Eastern Europe achieved astonishing results in the fields of industry, science, health and education. But, as Trotsky predicted as early as 1936, the bureaucratic regime ultimately undermined the nationalised planned economy and prepared the way for its collapse and the return of capitalism.

What is the balance sheet of the October Revolution and the great experiment in planned economy that followed it? What implications do they have for the future of humanity? And what conclusions should be drawn from them? The first observation ought to be self-evident. Whether you are in favour or against the October Revolution, there can be no doubt whatsoever that this single event changed the course of world history in an unprecedented way. The entire twentieth century was dominated by its consequences. This fact is recognised even by the most conservative commentators and those hostile to the October Revolution.

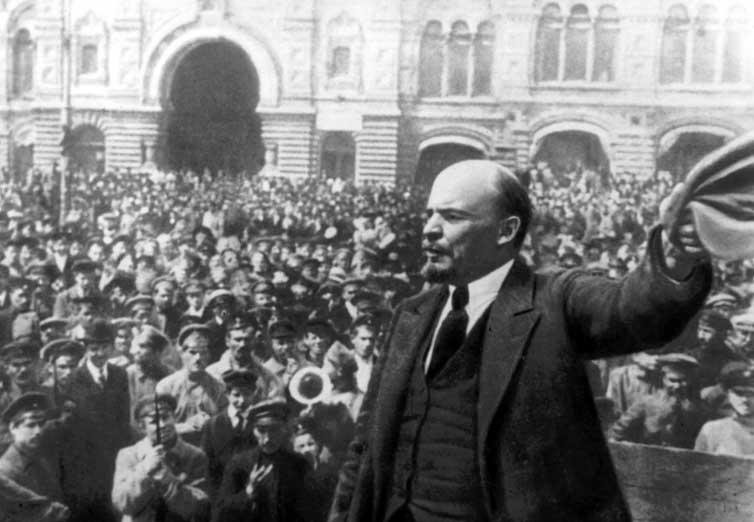

Needless to say, the author of these lines is a firm defender of the October Revolution. I regard it as the greatest single event in human history. Why do I say this? Because here for the first time, if we exclude that glorious but ephemeral event that was the Paris Commune, millions of ordinary men and women overthrew their exploiters, took their destiny in their own hands and at least began the task of transforming society.

That this task, under specific conditions, was diverted along channels unforeseen by the leaders of the Revolution does not invalidate the ideas of the October Revolution, nor does it lessen the significance of the colossal gains made by the USSR for the 70 years that followed.

The enemies of socialism will reply scornfully that the experiment ended in failure. We reply in the words of that great philosopher Spinoza that our task is neither to weep nor to laugh but to understand. But one would look in vain in all the writings of the bourgeois enemies of socialism to find any serious explanation for what occurred in the Soviet Union. Their so-called analysis lacks any scientific basis because they are motivated by blind hatred that reflects definite class interests.

It was not the degenerate Russian bourgeoisie but the nationalised planned economy that dragged Russia into the modern era, building factories, roads and schools, educating men and women, creating brilliant scientists, building the army that defeated Hitler, and putting the first man into space.

Despite the crimes of the bureaucracy, the Soviet Union was rapidly transformed from a backward, semi-feudal economy into an advanced, modern industrial nation. In the end, however, the bureaucracy was not satisfied with the colossal wealth and privileges it had obtained through plundering the Soviet state. As Trotsky predicted, they passed over to the camp of capitalist restoration, transforming themselves from a parasitic caste to a ruling class.

The movement towards capitalism has meant a big step backwards for the people of Russia and the former Republics of the USSR. Society was thrown back and had to learn all the blessings of capitalist civilization: religion, prostitution, drugs, and all the other ‘blessings’ of capitalism. For the time being the Putin regime has succeeded in consolidating itself. But its appearance of strength is illusionary. Russian capitalism, like the hut in the Russian fairy tale, is built on chicken’s legs.

The Achilles heel of Russian capitalism is that it is now linked by an umbilical cord to the fate of world capitalism. It is subject to all the storms and stresses of a system that finds itself in a terminal crisis. This will have a profound impact on Russia, both economically and politically. Sooner or later the Russian workers will recover from the effects of the defeat and move into action. When that happens, they will quickly rediscover the traditions of the October Revolution and the ideas of genuine Bolshevism. That is the only way forward for the workers of Russia and the entire world.