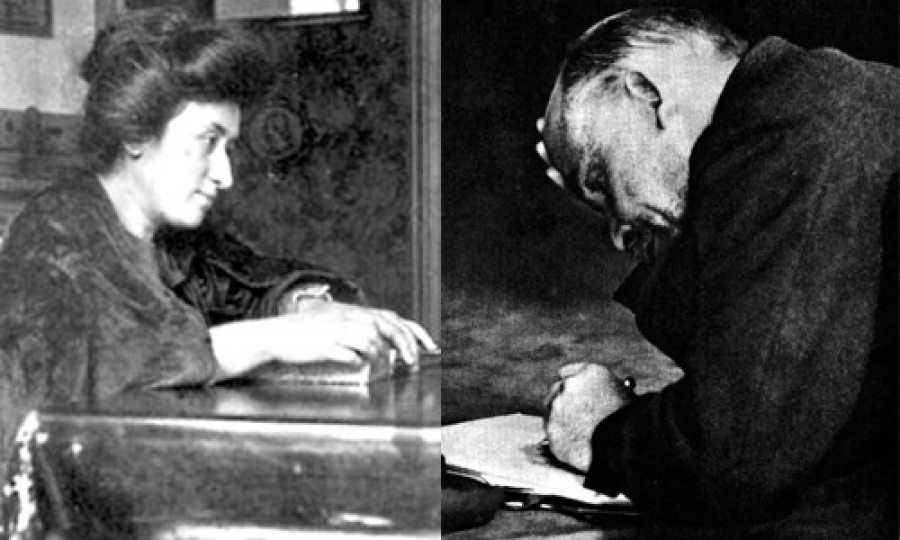

Few historical figures have been so badly misrepresented and misunderstood as Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-born Marxist revolutionary leader, who was murdered along with her comrade Karl Liebknecht, by forces of the German state one hundred years ago, on 15th January 1919.

On the centenary of her death, it is time to set the record straight on ‘Red Rosa’, her life and ideas. Most importantly, it is vital that we learn the lessons of the German revolution so that the sacrifice of Luxemburg and her comrades will not have been in vain.

Reform or Revolution

Rosa Luxemburg was born in 1871 to a Polish Jewish family in Zamość in Poland, which at the time was controlled by the Russian Empire. She got involved in revolutionary politics at the early age of 16, but was forced to flee the country in 1889 to avoid imprisonment for illegal political activity.

She went to Zurich, where she studied at the University and remained involved in the international revolutionary movement. She founded the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania with Leo Jogiches and other Marxists.

When she moved to Berlin in 1898 to participate in the German working class movement – at the time the most advanced and established in Europe – she joined the left wing of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). Here she consistently argued that the only way to escape the impasse of capitalist society was for the working class to take power into its own hands and organise society in its own interests.

She was a skillful organiser and agitator, and her revolutionary position brought her into sharp conflict with the likes of Eduard Bernstein, who was perhaps the most open representative of the revisionist (i.e. reformist) tendency inside the SPD at that time.

In a series of articles, Bernstein presented his view that capitalism had overcome its own contradictions through the expansion of credit and other mechanisms. As such, he believed that traditional methods of class struggle had become irrelevant and advocated for the working class and the SPD to collaborate with the bosses to reform the system.

Luxemburg demolished these ideas in her now-famous pamphlet Reform or Revolution, which remains a classic explanation of the need to completely overthrow capitalism, not merely tinker with it.

Mass Strike

In a Europe where other Social Democrats were struggling to assemble even the nucleus of the revolutionary party, it seemed that the SPD was a model to strive after. But Bernstein’s attempt to revise Marxism was the reflection of serious problems within the party.

The SPD was founded in 1875, in the context of a huge upswing in German capitalism following the country’s unification in 1871. From the 1870s to the early 1910s, German industrial production grew sixfold.

The growth of capitalism in this period created the basis for a powerful labour movement rooted in the working class. It also gave rise to a period of relative class peace from the defeat of the Paris Commune in 1871 to the end of the economic upswing in 1912, which shaped the conservative outlook of the SPD leaders. The immense bureaucratic apparatus of the party also became an attractive field for would-be careerists like Bernstein.

Rosa Luxemburg put herself at the helm of the fight against this bureaucratic degeneration. In 1905 she clashed with Karl Kautsky, the leading theoretician of the party and of the Second International, over the question of a political general strike. Clearly inspired by the Russian events of that year, she raised the political strike as an important weapon of the struggle in Germany, too.

Kautsky gave all sorts of excuses as to why a political general strike was impossible. In reality he had lost faith in the strength of the working class and preferred the method of peacefully forming a loyal parliamentary opposition.

The Great Slaughter

The outbreak of the First World War provided the ultimate litmus test of the party’s policy. Instead of calling for resistance to the bloody slaughter, the SPD deputies in the Reichstag voted in favour of extending war credits to the Imperial government. Only one voice in the party’s parliamentary faction was raised against the war: that of Karl Liebknecht.

The outbreak of the First World War provided the ultimate litmus test of the party’s policy. Instead of calling for resistance to the bloody slaughter, the SPD deputies in the Reichstag voted in favour of extending war credits to the Imperial government. Only one voice in the party’s parliamentary faction was raised against the war: that of Karl Liebknecht.

Leibknecht, along with Luxemburg, Franz Mehring and Clara Zetkin, organised what at first was a tiny revolutionary opposition within the SPD. But this grew as opposition from workers, soldiers and sailors to the war bubbled up.

By mid-1916 the tide was beginning to turn and the Spartacists (as this revolutionary group was called) had managed to channel the anti-war mood of thousands of workers. As the war dragged on and living conditions in Germany worsened, the promised rapid victory was nowhere to be seen.

Throughout the following two years the situation of the German masses only got worse, and pressure was mounting. When sailors mutinied at Kiel on the 3rd November 1918, a mass movement spread throughout the country: the German revolution had begun.

The German Revolution

Workers’ and soldiers’ councils started taking power first in Hamburg and Bremen, then Leipzig, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Nuremberg and Munich, and finally in Berlin on 9th November.

Workers’ and soldiers’ councils started taking power first in Hamburg and Bremen, then Leipzig, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Nuremberg and Munich, and finally in Berlin on 9th November.

The masses held in their hands the power to transform society, to end capitalism once and for all. But they lacked a revolutionary leadership that could guide them in this task. The councils (effectively, soviets) handed power to the workers’ traditional leaders: the Social Democrats.

The SPD leaders had no intention of breaking with capitalism. In fact, they allied with the worst elements of the old order – the reactionary generals – to disarm the movement of the masses.

Revolutions, however, are never fought halfway: one class must come out on top. What was needed in this context was a steeled revolutionary organisation that would have differentiated itself from the reformist parties and explained to the working class the need to complete the revolution.

Luxemburg and Liebknecht saw the need to complete the revolution, and tried to build an alternative leadership in the Spartacist League, and later as the Communist Party (KPD).

But whilst they attracted the most revolutionary and class-conscious workers, there was no time to train a party able to skillfully combine a variety of tactics to win a majority in the working class. As such the young party made a number of ultra-left mistakes.

The correct combination of legal and illegal methods was learnt by the cadres of the Bolshevik Party in Russia through over twenty years of experience. The young Communist Party in Germany did not have this time, having only emerged on the 30 December 1918 – in the middle of the revolution.

Building Bolshevism

Rosa Luxemburg tried to temper the ultra-leftism of the young Spartacists. But the fact that she had not been able to educate and steel a revolutionary party was not only down to a lack of time and her multiple arrests for anti-war agitation.

Rosa Luxemburg tried to temper the ultra-leftism of the young Spartacists. But the fact that she had not been able to educate and steel a revolutionary party was not only down to a lack of time and her multiple arrests for anti-war agitation.

Much has been made of Luxemburg’s differences with Lenin by anarchists and reformists alike. In particular, they use her criticisms of the Russian Revolution – made whilst imprisoned and isolated – to make out that she was an anti-Leninist or anti-Bolshevik.

However, she was incredibly aware that her analysis would be imperfect and adamantly refused to publish anything she wrote on the Russian Revolution while in prison, knowing that it would get distorted by the enemies of revolution. Despite her criticisms, she ended her aforementioned pamphlet with the words: “the future everywhere belongs to Bolshevism.”

Towards the end of her life, she came to realise the importance of a disciplined revolutionary leadership, and she and Liebknecht were caught in a race against time to create a Bolshevik Party in Germany. They tragically paid the price for losing that race with their lives.

A true revolutionary

In January 1919, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were hunted down and murdered by right-wing paramilitaries at the behest of the SPD government, following a failed spontaneous uprising of the workers of Berlin. The SPD government had suppressed the movement of the workers by force, using right-wing and monarchist troops in what was rightly called “a white terror”.

In January 1919, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were hunted down and murdered by right-wing paramilitaries at the behest of the SPD government, following a failed spontaneous uprising of the workers of Berlin. The SPD government had suppressed the movement of the workers by force, using right-wing and monarchist troops in what was rightly called “a white terror”.

Leading communists were arrested and an unofficial price of 100,000 German Marks was put on the heads of Luxemburg and Liebknecht. On 13 January, they were found and arrested by Freikorp officers (reactionary mercenaries paid by the state) and taken for interrogation. It was later claimed that Liebknecht was shot “trying to escape”. Luxemburg’s fate would remain unknown until her body was found in the Landwehr canal in Berlin, several months later on 31st May.

In fact both had been brutally murdered by the police thugs of the state. Luxemburg’s body showed clear evidence of how she had been struck on the head by a rifle butt as she was being led out of the building. So it was that the international working class suffered the loss of two of its most leading comrades.

All those who paint Rosa Luxemburg as a fellow traveller of anarchism, reformism, or anything less than a Marxist revolutionary do her a grave injustice. Rosa had no such weaknesses. Whatever disagreements she had with Lenin and Trotsky came from the position of an honest and capable revolutionary.

As Lenin said of Luxemburg, in response to her critics who make much of this or that mistake: “Eagles may at times fly lower than hens, but hens can never rise to the height of eagles…in spite of her mistakes Rosa was—and remains for us—an eagle.”