“It’s coming yet, for a’ that, that man to man the world o’er, shall brithers be for a’ that.”

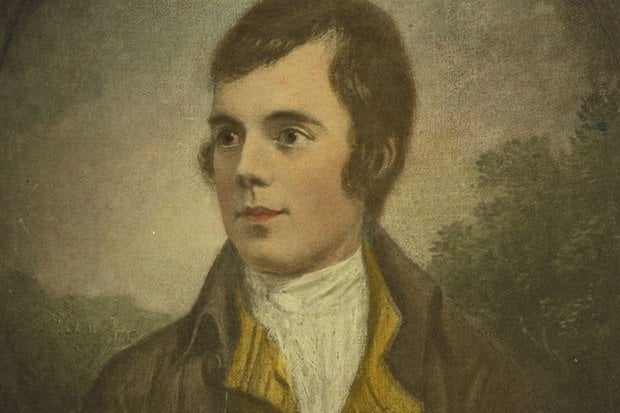

Robert Burns (1759-1796) the poet needs no further introduction. But Robert Burns the revolutionary democrat is another matter. It is a matter of great regret that nowadays it seems to have become the fashion among certain left circles in Scotland to renounce Burns. To some degree this is understandable. After his death, Burns was hijacked by the Scottish Establishment, who turned him into a harmless icon. On Burns’ night each January, upper class Scotsmen in kilts (!) make use of the great man’s anniversary to eat and drink to excess, declaim poems to the haggis, and generally make fools of themselves. This grotesque parody would, of course, have had Rabbie Burns splitting his sides with laughter. His poems, his politics, his philosophy, his life and his death – all bear witness against these stage Scotsmen and hypocritical Pharisees.

Unlike Byron and Shelley, who were members of quite wealthy families, Robert Burns (1759-96) was the son of a working gardener. He had only the most basic education and his early life was one of poverty and hard labour. When his father, who had strong Jacobite sympathies, died prematurely worn out and exhausted, the twenty four year old Burns and his brother were left with a poor, undercapitalised farm. The farm was bound to fail, not because Robert and Gilbert were bad farmers, but because they lacked the necessary minimum capital to work it properly.

Robert started to work when he was 14 years old. Work at the plough had severe consequences, which lasted the rest of Burns’ life. The effects of heavy agricultural work and under-nourishment undermined what was a fairly delicate constitution. In his own words, his life consisted of “combining the gloom of a hermit with the toil of a galley slave.” His first poem, Handsome Nell, was written at the age of 16 in praise of a fellow harvest worker. But it was not until the age of 25 that his exceptional poetic genius began to manifest itself, triumphing through adversity.

Most of Burns’ lyricism is written, not in English, but in Burns’ own tongue, the dialect of the Scottish Lowlands. His song is as natural as the song of a bird. This is poetry quite unlike the stilted verses we find in most 18th century poetry south of the Border. Both in content and in style it is in a world of its own. The style most often reflects that of Scottish traditional songs and ballads. But what is most interesting and original is the content, which is mainly drawn from the everyday experience of the mass of the Scottish people: ploughboys, soldiers, tinkers, market drunkards, and the serving-wenches of numerous inns.

The slightest acquaintance with the poetry of Scotland’s greatest poet reveals a world unknown to Byron and Shelley: the world of the ordinary working man and woman. It was not that Burns identified with the people, as Shelley did, from the outside. He knew the people, for he was one of them. In these works we enter into a tavern, we hear the laughter (for Burns, despite everything, could roar laughing), we taste the ale, we listen to the stories of ghosts and goblins. And Burns’ humanitarianism shines forth from every line. He is the friend of the underdog and the oppressed in every conceivable form – not just humankind, but lowly animals: as in his famous poem written to a field mouse whose home he has just unwittingly destroyed. Other poems are addressed to an old mare and a wounded hare. Such poems are not to be found elsewhere, unless we bring to mind Mayakovsky’s poem entitled Kindness to Horses, which is written in the same spirit.

The boundless love of life embodied in these verses convey the spirit of Burns’ own life. He loved men – and women – quite a few of them in his lifetime. Of his children, nine were born in “lawful wedlock”, and there were others too. This fact has been frequently used to criticise Burns, but in those days such things were by no means unusual. What was certainly unusual is that Burns looked upon all the children he fathered as his own, and not just the mother’s, responsibility. He even celebrated the birth of a love-child in a poem that must have scandalised the respectable church-goers. It begins: “Thou’s welcome, wean.” (“You are welcome, child.”).

In the first decade of the 21st century we are plagued with the malignant curse of so-called “political correctness” which is preached by people whose veins are full of Perrier water in place of blood. The progressive snobs from the “educated” middle class spend all their spare time (and they have a lot of it) fiddling and fussing over this or that trivial matter. One is tempted to say tilting against windmills, except that such an analogy would be manifestly unjust to Don Quixote who, despite his madness, was inspired by a nobility of spirit. One could laugh with Don Quixote and Robert Burns, but never with spineless, narrow and mean-hearted people.

Burns may have made mistakes in his life, but even in his mistakes he showed a passionate human nature. The proletariat in its fight against Capital requires a strong fighting spirit tempered by a healthy sense of proportion and a sense of humour. It will inscribe on its banner the slogan beloved of Marx: “Nihil humano alienum mihi puto”, and not the wretched petit bourgeois caricature that brazenly proclaims: “I regard everything human as alien to me” – and expects to get applause from it. As old Hegel once wrote: “By the little with which the human spirit is satisfied we may judge the extent of its loss.”

“Legitimacy and illegitimacy were meaningless words to him,” says the Introduction to his Collected Poems and Songs, “he spat the morality that begot them out of his mouth.” (R. Burns, Poems and Songs, p. 9.) Burns was a rebellious spirit that revolted against all forms of oppression and hypocrisy. Brought up as a Presbyterian, he hated the clergy with its religious cant, as we see from the poem “Holy Willy’s Prayer”. Here is an example of his anti-clerical verse:

KIRK AND STATE EXCISEMEN

Ye men of wit and wealth, why all this sneering

‘Gainst poor Excisemen? Give the cause a hearing.

What are your Landlord’s rent-rolls? Taxing ledgers!

What Premiers? What ev’n Monarchs? Mighty Gaugers!

Nay, what are Priests? (those seemingly godly wisemen?)

What are they, pray, but Spiritual Excisemen!”

This hatred was extended to lawyers, wealthy landowners, aristocrats, politicians and kings. Tam O’ Shanter is Burns’ poetic masterpiece. The climax is a witches’ Sabbath, attended by all kinds of gruesome sights. And pride of place in this hellish scene is given to lawyers and priests:

“Three Lawyers’ tongues, turned inside out,

Wi’ lies seamed like a beggar’s clout;

Three Priests’ hearts, rotten, black as muck,

Lay stinking, vile, in every neuk.”

How his poetry ever succeeded is something of a miracle. With no formal training he managed to produce the finest lyrical poetry that ever emerged from these Isles. Only Shakespeare and perhaps Chaucer can rival him in this sphere, and Chaucer is now unintelligible to the modern English reader except in translation. But the position of Burns is similar, since he wrote mostly in Lowland Scots dialect (some would say language), which, south of the border at least, can only be understood with the aid of a vocabulary.

The quality of Burns’ verse is extraordinary. There is nothing contrived or artificial about it. It has the naturalness of the song of a skylark. How he managed to achieve this is a mystery. Probably, it was partly the result of his acquaintance with a mass of old Scottish border ballads and songs which instilled into his mind a strong sense of rhythm, lyricism and musicality. For it is above all the musicality of his verses – their strong kinship with song – which causes such a lasting impression. As a matter of fact, many of them were intended to be sung, and the appropriate tune is often indicated.

In 1786, while he was still toiling on the farm, and on the point of giving up and emigrating, like so many of his compatriots, to the Indies, his first book of verse appeared in print. It was an instant success and soon was being read by all social classes. A second edition appeared, and Burns became a celebrity, staging a tour of Scotland and attending the best salons in Edinburgh. The spectacle of a Scottish workingman (for that is how he would have appeared to them) writing poetry no doubt struck them as entertaining and original. After all, the idea of the “noble savage’ was then in vogue across the Channel, and French influence was still quite strong in Edinburgh’s cultural elite.

Success did not change Robert Burns very much. Upon leaving the upper class salons, he still needed to make a living. He set up as a tenant farmer in the county of Dumfries. But once again, he lacked the necessary capital to set aside money for hard times, and so he entered the Customs and Excise at a low rank, earning £50 a year.

But the events of 1789 changed everything. As a convinced revolutionary democrat, Burns sympathised with the French Revolution with all his heart, and gave vent to these sympathies in his verses. These were harsh times, and nowhere more so than Scotland. Pitt’s secret agents were everywhere. Less than half a century had passed since the Scottish clans had risen against the English Crown, and Scotland’s loyalty could not be taken for granted. In an atmosphere of hysterical paranoia, many people were being accused of sedition, treason, or sympathising with the reform movement – itself a by-product of the French Revolution.

Burns greeted the French Revolution with all his might. His enthusiasm for the revolutionary cause led him to abandon all caution. In his poem, Why Should we idly waste our Prime? we find the following explosive line:

“Proud Priests and Bishops we’ll translate

And canonise as Martyrs;

The guillotine on Peers shall wait;

And Knights shall hang in garters.

Those Despots long have trod us down,

And judges are their engines;

Such wretched minions of a Crown

Demand the People’s vengeance!

Today tis theirs. Tomorrow we

Shall don the Cap of Libertie!”

Burns was drawn to the Revolution with every fibre of his being. His sympathy for it was not the product of abstract philosophical considerations. He identified with the Revolution because he himself was one of the downtrodden and oppressed. His identification was personal and total. It came from the bottom of his heart. When Burke (an Irishman by birth, though a defender of the English oligarchy and crown) attacked it in his notorious Reflections on the French Revolution, he wrote the following denunciation:

“Oft have I wonder’d that on Irish ground

No poisonous Reptile has ever been found;

Revealed stands the secret of great Nature’s work;

She preserved her poison to create a Burke!”

This kind of thing was extremely dangerous. The English poet William Blake observed that under these conditions, to defend the Bible would cost a man his life. A single word out of place could lead to denunciation, arrest, and deportation to the notorious Botany Bay convict settlement in Australia. For someone with a weak constitution like Burns, this would have meant a death sentence. Only his connections with influential people saved him from this fate.

But the establishment got its revenge in other ways. In 1789, the year of the fall of the Bastille, he had obtained a post in the customs and excise office. In 1791 he was able to give up farming to act as an ordinary exciseman (customs officer) in Dumfries at a salary of £70 a year, which was raised to £90 in 1792 when he was promoted to the position of port officer. But now his further advancement was blocked as a result of his outspoken political views. His health was further undermined by serious financial difficulties. Slowly, remorselessly, his spirit was crushed, and he entered his last years in a state of deep depression.

On 21st July1796, the combined effects of a heart weakened by excessive labour and repeated bouts of rheumatic fever, finally took their toll. Robert Burns died at the age of 37 in the direst poverty and under the threat of a debtor’s prison. On the day of his funeral, his widow, once more in childbirth, was literally without a shilling. His funeral was one of the biggest demonstrations in Scottish history. Had it not been for the heavy presence of the military, it would have been even bigger.

It is the common fate of revolutionaries to be turned into harmless icons after they are dead. Burns was not a tame Scottish icon. He was a rebel and a subversive who hated the very Establishment that now tries to speak in his name. He stood for revolution – not an imaginary revolution, but one in the image of 1789-93. Not just in France, but in England and Scotland: “It’s coming yet, for a’ that, that man to man the world o’er, shall brithers be for a’ that.”