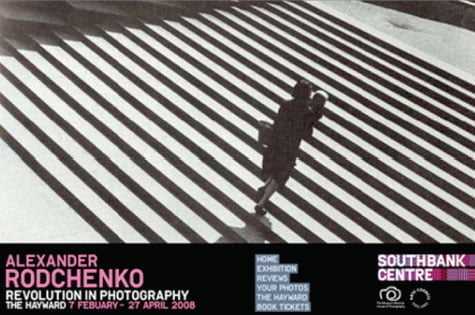

A

major exhibition of the photographic work of Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956) is

currently on at the Hayward Gallery in London. It is sponsored by Roman Abramovich, the

billionaire owner of Chelsea Football Club and a supporter of the Moscow House

of Photography Museum whose director, Olga Sviblova, curated the show. This important Russian

artist is

considered one of the most versatile avant-garde artists to have emerged after the Russian

Revolution. He was a part of the working group called the ‘constructivists’

whose general slogan was ‘Art into Life’, and their goal was "to unite

purely artistic forms with utilitarian intentions."(1) Originally

Rodchenko worked

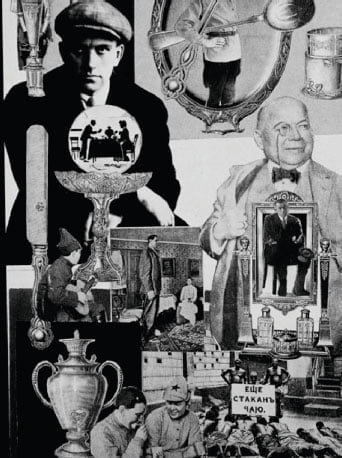

as a painter and sculptor, before moving into graphic design and then

photography, using ground-breaking photographic techniques such as photomontage

and unusual camera angles, which this exhibition highlights.

Approximately

120 original prints and photomontages are featured with accompanying text,

quotes and video, to give the viewer a sense of history and context. The Hayward exhibition

is good by virtue of the art works themselves but unfortunately I feel that the

curation leaves a lot to be desired. Although the sub-heading for the show is ‘Revolution in Photography‘, the

Revolution part is conspicuously missing.

The

development of Rodchenko’s photography is traced over a period of two decades

and a fair amount of detail is used in describing his life and work in terms of style and form,

but unfortunately the political content of his work is just skimmed over.

If

you happen not to know much about this period in history – as most people don’t

– and follow the logic of the show’s emphasis, you would probably go away

thinking Rodchenko’s pioneering work was a product of his innate

‘avant-guardeness’ and that his motivation was a personal, individual one. To

be ‘cutting edge’ in the world of art was good enough for him.

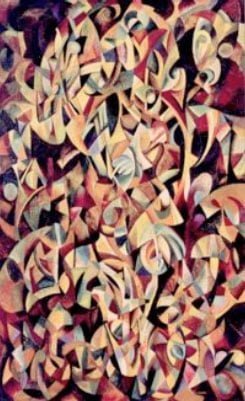

For

example, in his early work he was a painter and sculptor in the futurist style.

But by 1921, he abandoned the paintbrush for the mediums of the applied arts

like poster design, clothes design and photography, to name a few.

By

1921 he was exclusively creating art that was useful, accessible and in the service of

social change. One might ask why the sudden change? The fact that a socialist

revolution was taking place at the very time of Rodchenko’s radical artistic

transformation is completely glossed over by the Hayward exhibition. Yes, the

Hayward exhibition gets all the dates right, but any description explaining the

enormous impact political events had on Rodchenko’s work is nowhere to be

found. The new social outlook of his work is never linked with the outward,

immensely social nature of the revolutionary process. After all, collectivity,

community and the redistribution of wealth are at the root of socialism.

With

a minimum of research, one can easily discover that Rodchenko wasn’t just

“supporting the Bolshevik cause”, as it is quickly described in the exhibition’s

programme, but that he was in fact an avowed and dedicated communist who

proudly declared himself for the revolution. He was one of the few artists who

identified himself with the new revolutionary government of the Soviets (the

Russian word for councils).

As

is so often the case, the early part of the revolution, led by Lenin and

Trotsky, and the later part, led by Stalin, are not differentiated by the Hayward.

After Lenin’s death and Trotsky’s banishment, the revolution took on a totally

different political and ideological trajectory under Stalin in the 1930s.

So

it is mostly by omission, but also by overt bias, that this exhibition

reinforces all the old negative stereotypes about the Russian Revolution, and

it fails to explain, even in a cursory way how

the rise of the Revolution, and then its degeneration under Stalin, impacted upon

Rodchenko’s work.

However,

the facts are that the Russian Revolution of 1917 ended the rule of the Tsar

and was replaced with a radical new form of socialist government. Contrary to

popular belief, the Soviets of the early days of the revolution, were actually

genuine popular organs of mass democratic control. They seethed with the will

of the average Russian, and from them came some of the most progressive

policies in the world – even when compared to today.(2) For the first time

anywhere, workers’ democracy was installed and capital punishment abolished.

There was land redistribution and the remnants of serfdom were abolished, as

the peasantry was emancipated from its huge debts to the landowners. Capitalist

exploitation ended and was – for a while – turned into workplace democracy

including equality for women.

Collective kitchens, childcare and laundries, the right of divorce,

decriminalization of abortion, decriminalization of homosexuality, the

elimination of the category of illegitimacy, recognition of the right of

oppressed nations to self-determination, and the flourishing of national

minorities was established. And, most importantly the Soviet government, under

the helm of the Bolsheviks, ended Russian involvement in the First World War.

So

it wasn’t just Rodchenko and his circle of artists who were trying to create

something new, as the exhibition would have us believe, but also the whole of

Russia. They were all trying to build an entirely new world – and a new kind of

art was just one part of it.

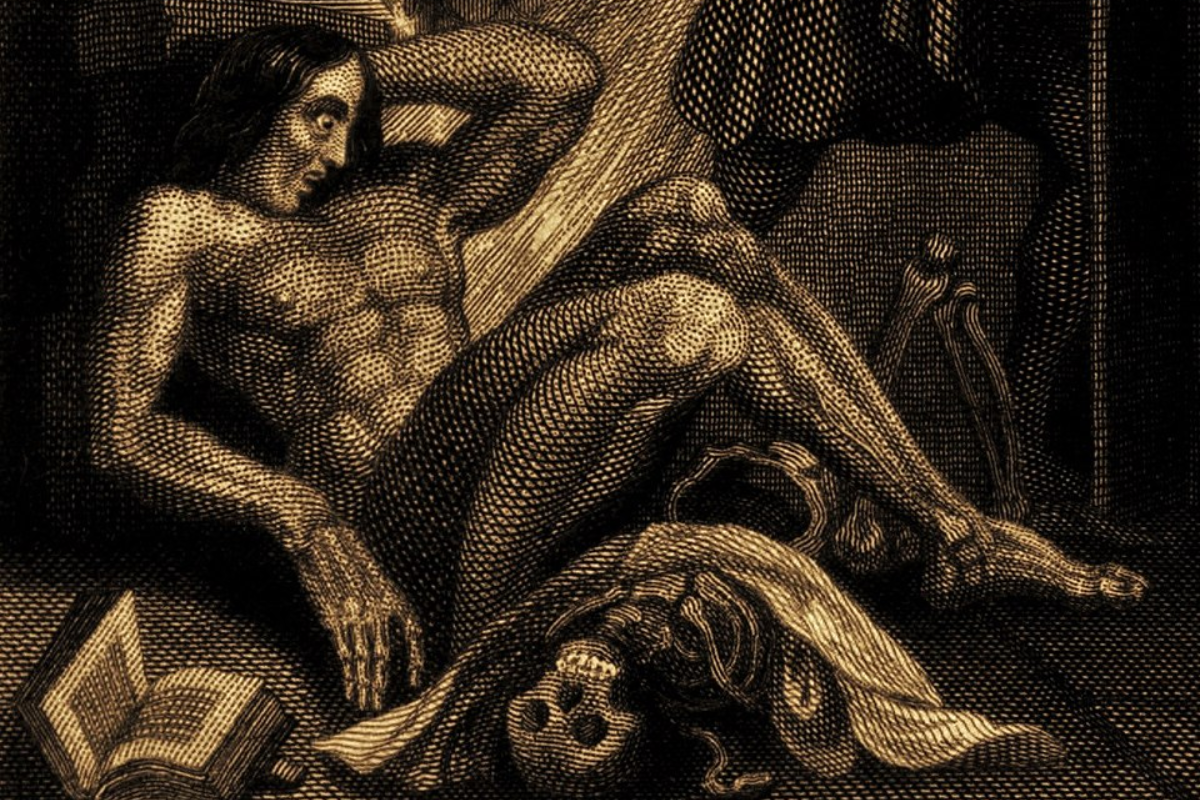

During

this time, Rodchenko became an important leader in a new experimental art

called ‘constructivism’ which looked to industry

and production for inspiration. Rodchenko’s involvement in this movement is covered – but to know the core ideas

behind the movement, one will have to look elsewhere.

And

one need go no further than the constructivist manifesto itself. Co-authored by

Rodchenko and his partner Vavara Stepanova, it is very explicit – unlike the

Hayward exhibition. The very first point is “Our sole ideology is Scientific

Communism”. In point three of the program, the style of constructivism is

described as “…tempered and formed on the one hand from the properties of

Communism and on the other from the expedient use of industrial materials”.

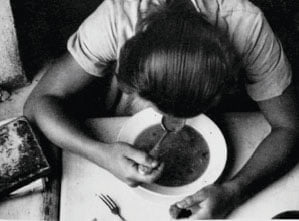

One

of the techniques Rodchenko is so lauded for is his pioneering use of extreme,

unconventional camera angles. But once again, the Hayward sees it as all form

and no content. One of the basic ideas

of Marxism is to see things in context – from all possible angles – whether

they are historical, economic or political. A Marxist believes that a big part

of why things are the way they are is in their relation to other things.

Context is paramount for a Marxist understanding of how things have developed

and will develop in the future. So, I immediately read Rodchenko’s use of the

technique of shooting things from surprising angles as a visual expression of

this Marxist idea. Not to mention a renunciation of the traditional posed,

front-on, head and shoulders portraits of the accepted photography of the day.

Rodchenko says “Photograph and be photographed. Record a

person’s life, not just a single ‘synthetic’ moment.”

The

real message intended by the exhibition can be seen and heard in the short

documentary video about Rodchenko (produced by the BBC) that is constantly looped

upon first entering the gallery. The film begins by describing his work,

acknowledges his innovations – again, mostly in terms of form and style – but

quickly skips to the later period of his work in the 1930s when he participated

in Stalinist propaganda. Underscored by sinister music, the film describes how

Rodchenko retouched and manipulated photos to hide the fact that convict labour

was used in the building of the White Sea-Baltic Canal. It tells us how he also

blotted out the faces of those in photographs that had fallen from Stalin’s

favour.

The

film, just like the exhibition, fails to differentiate the two very different

periods of the revolution. And

the censorship that Rodchenko participated in is presented as if it is some

inherent characteristic of anyone who was a part of the Russian Revolution. It

turns out Rodchenko, for fear of falling victim to Stalinist repression, used

the jet-black ink to blot out the faces of those who might incriminate him from

his own book of photographs! Not surprisingly, it is around this time that you

see another marked change in Rodchenko’s style that perfectly coincides with

the rise to power of the new regime.

Having

been pretty frugal with political content, the exhibition now starts to give us

a bit more detail once everybody’s favourite villain – Stalin – is on the

scene. It describes Rodchenko’s fall from grace and with ‘Socialist Realism’

imposed by the state as the new look of the Soviet Union, he experienced

increased criticism, isolation

and loss of stature and income. At this point, Rodchenko turned to reportage photography, but

the new 1933 law requiring a permit to photograph restricted him, so he focused

on things like sport.

But,

once again, the exhibition only provides a superficial understanding. One of

the blurbs that introduce this period reads, “From the 1930s the political climate was more hostile to the

avant-garde and Rodchenko became more isolated”. On the surface, this is

factually true. But I bet you it wasn’t merely the ‘avant-gardeness’ of the

avant-garde that offended Stalin. It was probably that Rodchenko and the social

outlook of his work were an expression of the real ideas in the struggle for socialism

– a classless society based on common ownership and democratic workers’ control

and NOT the caricature of these ideas propagated by Stalinism in order to

secure the power and privileges of a new ruling bureaucratic caste.

So,

although the art on display is well worth seeing, the exhibition at the Hayward

fails to make any connection between art and politics.

Indeed

I think Rodchenko’s work is revolutionary, a great example of communist art.

But unlike the Hayward, I’m not afraid to say it!

The Hayward

The Hayward

Southbank Centre

Belvedere Road

London SE1 8XX

U.K.

FOOTNOTES

1. Vladimir Tatlin

2. Read American journalist John Reed’s ‘Ten Days

That Shook the World’ for an eyewitness account.

3. The Constructivist Program by A. Rodchenko and

V. Stepanova 1921