There are two Pre-Raphaelite exhibitions on show in Birmingham until January 2025 which are both well worth a visit.

At the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery is ‘Victorian Radicals: From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts and Crafts Movement’, and a few miles away at the University of Birmingham’s Barber Institute is ‘Scent and the Art of the Pre-Raphaelites’.

These collections feature vibrant paintings, exquisite drawings, and an array of decorative arts including jewellery, glass, textiles, and metalwork. Collectively, they explore the revolutionary vision these artists had for both art and society.

Realism

One of the most striking aspects of the Pre-Raphaelites’ approach to art is their commitment to realism.

This was in opposition to the heavily staged and idealised pieces popular amongst the Royal Academy at the time.

For example, the Pre-Raphaelite painters often went into the countryside to paint natural scenes with remarkable accuracy, a practice very unusual for the time.

In this short video, Victoria Osborne, Co-Curator of the Victorian Radicals exhibition, discusses Joseph Southall’s artwork New Lamps for Old.

Southall died #onThisDay (6 Nov) in 1944.

You can see this piece in #VictorianRadicals exhibition (open Wed – Sun) until 5 Jan 2025. pic.twitter.com/RTidto2aB1

— Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (@BM_AG) November 6, 2024

Yet their works were not merely direct reflections of what they saw in front of them.

This immensely detailed approach created rich, multi-layered pieces, within which the Pre-Raphaelites wove in historical, literary, and personal references to create complex narratives.

Later Pre-Raphaelites took this a step further, heightening this realism and detail in their works to the point of unrealism.

This attention to detail was not restrained to just what could be seen, but – as the Barber Institute exhibition demonstrates – aimed to play on all the senses to evoke emotions in the viewer.

Social critique

The Pre-Raphaelites were not merely concerned with aesthetic innovation.

From the outset, their desire to challenge the artistic conventions of the time drew from a belief that art could be a powerful tool for social reform, moral education, and the pursuit of truth.

The Pre-Raphaelites therefore often used their art to comment on social issues, critique contemporary society, and explore complex moral themes. This occasionally led to controversy, particularly when applied to religion.

A wonderful evening at @BM_AG for the Victorian Radicals exhibition pic.twitter.com/0BBGKKKevy

— Holly (@_______holly) February 8, 2024

In Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents the holy family is portrayed as ordinary people with everyday surroundings, including wood shavings on the floor.

This portrayal drew criticism from notable figures like Charles Dickens, who disparaged the (realistic) depiction of Mary as looking like a “hideous alcoholic.”

The Pre-Raphaelites were also heavily influenced by the art critic John Ruskin, who believed that earlier societies were more organically whole than the fragmented industrial society of his time.

Many works are set in a romanticised mediaeval period as a result, with the artists counterposing Arthurian legends and mythical narratives to the industrial revolution taking place around them.

Industrial Revolution

Yet the Pre-Raphaelites’ critique was more nuanced and engaged than mere backwards-facing escapism. They viewed their art as a remedy to the harsh realities of Victorian industrialisation.

The focus on the importance of nature in many Pre-Raphaelite pieces can be seen as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution’s grime and pollution, for example.

Their concern was that capitalism and industrialisation were eroding community bonds, diminishing beauty, and reducing the quality of art in everyday surroundings such as homeware, architecture, and decoration.

This concern developed in two directions from its beginnings in the Pre-Raphaelite movement as industrialisation continued to spread: the Arts and Crafts movement, and the Aestheticism movement.

The Arts and Crafts movement, as seen in ‘Victorian Radicals’, championed the value of handcrafted products, seeing them as a way to combat the alienation, poor working conditions, and loss of craftsmanship and individual creativity brought about by mass production.

‘Scent and the Art of the Pre-Raphaelites’ exhibits the development of Aestheticism, which diverged from the Pre-Raphaelite belief in “art for truth’s sake” and instead argued for “art for art’s sake”. That is, art should exist to provide beauty, rather than serve a function or impart a lesson.

Modern radicals?

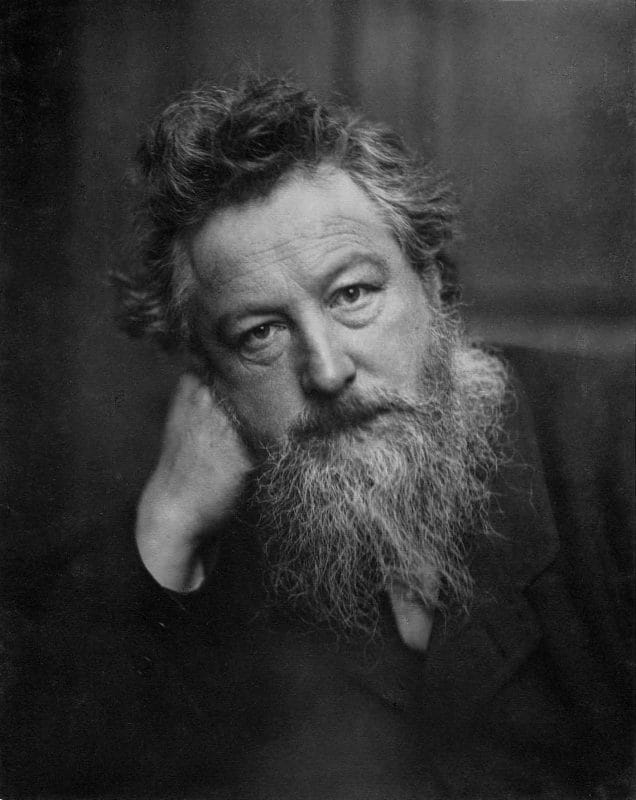

Famous Pre-Raphaelite figures like William Morris – who became a Marxist and a leading figure of the British labour movement – saw their work as an explicit rejection of capitalism, and did not stop at critiquing the society around them.

They instead participated in revolutionary socialist and anti-imperialist movements alongside and through their artistic pursuits.

It is no surprise that there has been a resurgence of interest in the Pre-Raphaelites – along with the Arts and Crafts movement, and even the more escapist Aestheticism movement – today.

The ideas of the Pre-Raphaelites continue to resonate for audiences today, offering a perspective not only on the current relationship between art, labour, and society, but the potential that exists for a more harmonious and beautiful world.