The discussion around diet in our media today is a monotonous sermon preaching that the problem begins and ends with the individual.

The root cause of the global nutrition epidemic is supposedly down to a lack of will, lack of discipline, and a lack of intelligence.

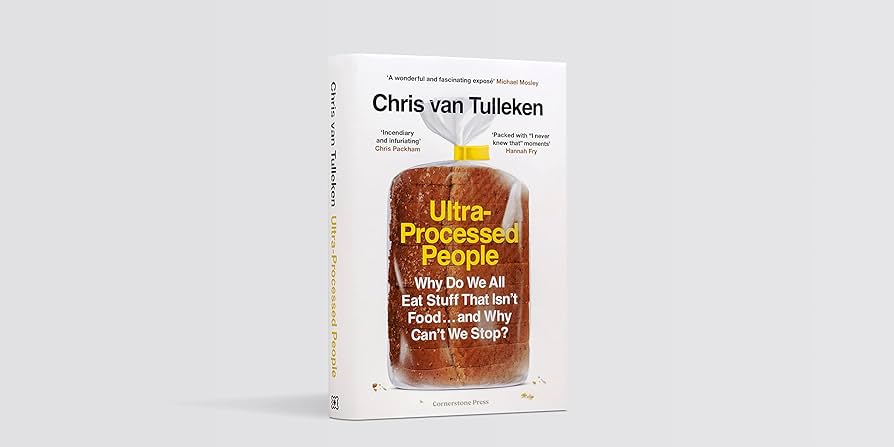

In contrast to this, Dr Chris van Tulleken’s book Ultra-Processed People looks at how the way in which the food industry giants produce our food for profit is making us unhealthy.

Ultra-processed food

Analysing a wide range of research, van Tulleken challenges the consensus that humans have just become lazy and greedy. Instead, he suggests that the dietary issues we see today – growing obesity, alongside rising malnutrition – are because of a drastic change in our modern diet: ultra-processed foods (UPF).

UPF is a scientific category of food, designed to be used in analysing food systems rather than individual foods. It is primarily useful for understanding the interconnection of our diets with the system that produces them.

The hallmarks of UPF are the addition of stabilisers, emulsifiers, gums, and lecithin you’ll never find in a supermarket or ordinary kitchen. The key to what these ingredients have in common is this: they save corporations money compared to other ingredients.

Health epidemic

As the book goes on, van Tulleken further explains that the health issues we see in the UK today are because of overconsumption of UPF.

He argues that while increasing exercise is the common solution put forward by health professionals and corporations alike, and it is good to exercise, increasing exercise will not increase our bodies expenditure of calories.

Drawing on research comparing hunter-gatherer tribes to office workers, the book demonstrates that these groups burn the same number of calories in a day regardless of drastically different activity levels.

The conclusion Ultra-Processed People points towards is that it’s not what you do – it’s what you eat. Specifically, it is the UPF we eat.

Ultra-processing breaks down cheap food into its constituent parts; reformulates them sans vitamins and fibre; and bulks them out with additives to improve texture, colour, and taste. One example given is ice cream, which in almost all cases is made using emulsifiers and gum as a replacement for more expensive, harder to store eggs.

Every component of UPF has minimal nutritional value, yet is designed to make you want more. There is growing evidence that UPF activates the brain like alcohol and drugs.

Food access

Alongside this research is growing evidence that UPF increases our chances of developing cancer, dementia, and inflammatory bowel diseases.

Yet for many, consuming UPF is the only option.

Some three million people in the UK don’t have access to a shop that sells raw ingredients within 15 minutes of their home (by public transport). Almost one million people in the UK don’t have a fridge; two million have no cooker; three million have no freezer; and the cost of energy is still sky high.

In deprived areas of England, there are more than twice as many fast-food outlets (per capita) compared to more affluent areas. In the developing world the situation is even worse, where fizzy drinks are often cheaper than water.

Even for those with access to fresh ingredients and basic amenities, most do not have the time or budget to sink into preparing every single thing they eat from scratch.

What is needed is affordable canteens at work, schools, and in neighbourhoods, which would be able to provide everyone with high-quality nutritious food.

But being cheaper to produce and addictive to eat means that UPF pulls in the best profits for the capitalists – and so dominates supermarket shelves.

Workers’ control

The book is thoroughly worth a read for anyone interested in how and why we eat the way we do.

Aside from nutrition, the book also goes into, for example, the environmental harm of the intensive farming required for UPF. It uses the story of Danone – where the former CEO tried to implement policies like eco-friendly production, and shareholders quickly rallied to have him fired to defend their profits – as a concrete example of how profits will always come first.

Yet the main shortcoming of the book is in its conclusion. After outlining extensively that it’s the market that pushes UPF despite its dangers, it falls flat with a vague call for government regulation of the food industry giants, citing the 2018 sugar tax as an example.

But capitalists trying to cut their costs by feeding us rubbish is as old as capitalism itself – Marx was talking about the adulteration of bread going back to the beginning of the 18th century.

In reality, if we want a food system that protects our health, we need to take the economic system into our own hands. Only then can we build a food industry that values our health, not the capitalists’ profits.