There has been a slew of films and TV shows released in the past few years that have dealt squarely with capitalism and class struggle. Don’t Look Up, Squid Game and Sorry To Bother You are but a few examples.

Now, Ruben Östlund’s Palme d’Or winning Triangle of Sadness can join this pantheon of class-conscious cinema.

Similarly to other current releases, such as Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery and The Menu, Östlund’s latest offering takes aim at the elites, skewing the super-rich.

Östlund ditches all subtlety in this side-splitting, slapstick satire of the wealthy. Bourgeois heiresses and tech billionaires alike are mercilessly exposed as wretched, empty creatures, completely out of touch with the real world.

Ship of fools

We are introduced to the film’s characters with a heated argument between social-media-influencer couple, Carl and Yaya, over a restaurant bill.

Here, Östlund offers some interesting commentary on bourgeois relationships and gender roles under capitalism. Yaya ends the discussion by revealing the transactional way that the rich view their relationships: “I like you. You like me. It’s good business.”

But this opening act merely preludes the more substantial second act, which takes place on a luxury yacht, packed with the mega-rich, their wives, and their mistresses.

From the get-go, the insanity of this wealth is ridiculed. For example, we see a helicopter air-dropping a package onto the yacht, containing just three jars of Nutella for one of the guests.

Among the cartoonish cast, we meet an oafish Russian oligarch who got rich on the back of the collapse of the Soviet planned economy; an elderly English couple who made their fortune in arms dealing (or “spreading democracy” as they euphemise); and a rich German woman who, after suffering a stroke, can only utter the words “in den Wolken”, or “in the clouds” – which is certainly where these ladies and gentlemen reside.

Below deck, however, we see a Morlock-like underclass of low-paid, mostly migrant workers, who keep the ship afloat. To the rich passengers, these workers are invisible. When Yaya interacts with one of the workers, Carl confusedly asks: “why are you talking to the crew?”

Lost at sea

But in the third act, this class hierarchy is thrown overboard when the ship capsizes. A handful of survivors – passengers and crew – are washed up on a desert island and forced to survive in a Lord-of-the-Flies-esque struggle.

Stranded and isolated, the riches of the yacht’s billionaire passengers have no value whatsoever. Only Abigail, a Filipina ‘toilet manager’, is able to provide for the group by catching fish.

When an argument erupts over how the food should be distributed, Abigail offers a cutting indictment of the idle classes:

“I caught the fish. I made the fire. I cooked the fish. I did all the work. What did you do? […] Maybe you shouldn’t be so lazy and dependent on me”

Here, Östlund points towards an idea that until recently would have been considered too radical for the silver screen: workers create all of the value in society, while the rich are mere parasites; the workers, not the rich, should be in control.

Limits of liberalism

But it is at this point that the limits of Östlund’s commentary become apparent. After Abigail becomes the matriarch of this new island society, she abuses her power by granting herself privileges, eliciting sexual favours from Carl, and using her position to terrorise the others.

Östlund falls back on the typical liberal prejudice that if the working class were to take power, they would vengefully replicate the same exploitation and oppression that preceded it.

This sneering idea – that ‘the revolution would devour its own children’ – is to be found everywhere among the liberal opponents of revolution; and it does nothing but denigrate and hold back the struggle for socialism.

Östlund openly revealed this viewpoint in an interview with the Independent, in which the director said:

“There is a conventional way of looking at class: the poor people are nice and rich people are mean…I say ‘No, they are human beings’, and they are going to maybe be mean or good…”

In other words, human nature is fundamentally flawed, and there is no hope of ever changing society for the better.

Workers’ power

Such pessimism reflects the typical outlook of the petty bourgeoisie: repulsed by the excesses of capitalism, but equally cynical about the prospect of workers’ power and socialism.

This is made abundantly clear in the scenes featuring the Russian oligarch and the ship’s alcoholic ‘Marxist’ captain (Woody Harrelson). Far from being class enemies, these characters are portrayed as mirror images of each other. They get on like a house on fire, with the Marxist captain merely entreating that the rich pay more taxes.

It is no surprise, therefore, that in the same Independent interview, Östlund ponders: “Are we living to improve the economy or is the economy there to improve our lives? It’s almost like we have forgotten about the qualities of capitalism.”

The mess we see around us today, however, is all that capitalism has to offer.

Triangle of Sadness reflects the growing mood of radicalisation in society. And it certainly does a good job of lampooning the super-rich.

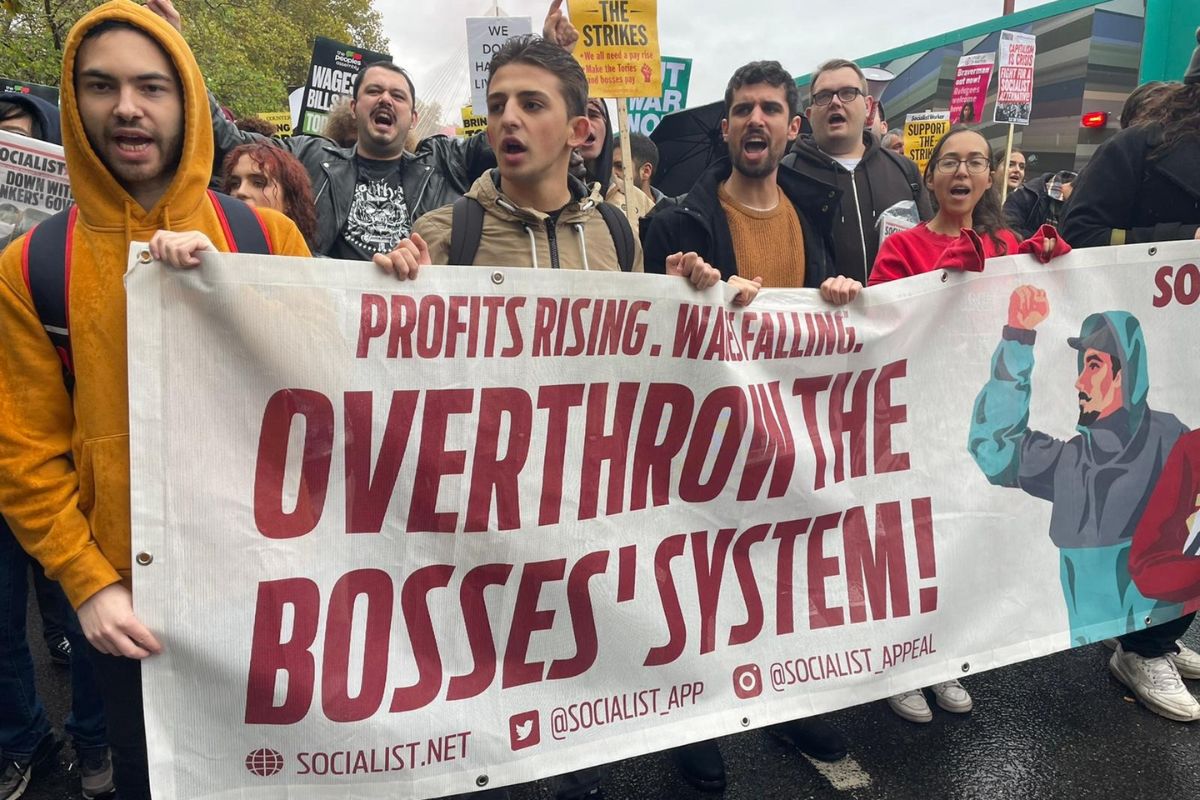

But for all its sledgehammer satire, Östlund pulls his punches right where it matters: refusing to accept the need for the working class to overthrow capitalism and take power into its own hands.