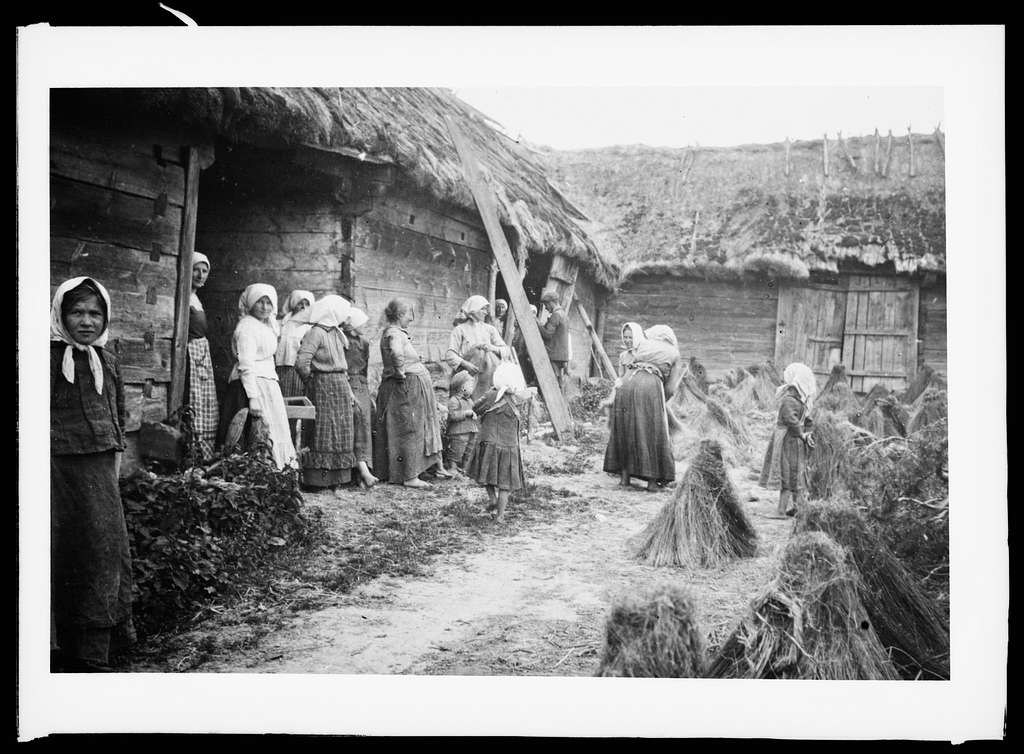

Władysław Reymont’s The Peasants, one of the few Nobel prize recipients for literature in Polish history, has tormented generations of college students as compulsory reading. Four opulent volumes vividly describe the everyday life, customs, and traditions of the Polish peasantry. That it is written in their language from a century ago makes the lecture a torture for many.

It is then a tremendous merit for the recent film adaptation to not only bring The Peasants to life again, but do so with force and without losing any of its ethnographic value. And to top it off it brings from the original story all the elements needed to comment on the fate of women in conservative Poland today, and more generally throughout the world as a whole.

Spectacle

One cannot begin to describe the film without speaking of the incredible technique of its production. After the traditional filming process was over, it was then painstakingly recreated frame by frame in oil paintings. Seventy artists in studios across Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Serbia worked over 200,000 hours to create some 40,000 canvases, using 1,350 litres of paint.

This absolutely colossal initiative results in a breathtaking spectacle. The sheer grandeur of craftsmanship contained in some scenes is enough to bring a tear of awe to the eye. In the process the artists also brought to life some of the masterpieces of Polish realism: paintings of Chełmoński in particular, but also Wyczółkowski and Masłowski feature heavily throughout the film.

The main focus is the story of Jagna, a young village beauty, whose interests lie with her arts and crafts rather than worldly affairs. In her we witness how individuals, particularly women, matter not in a patriarchal rural society. Attempts of going against the stream of tradition end up very badly for anyone who dares not to follow.

The land

This epic portrayal of the peasantry is of particular interest to Marxists. An understanding of the peasantry as a class can be a little bit vague and abstract for us today. This is especially the case in Britain, which was one of the first countries to brutally eradicate this class in the mills and factories of capitalism.

In Poland under the Russian Empire this process was only starting in the late 19th century. This is depicted in the story with the conflict over the closures of the village commons.

The film also shows the contradictory nature of the peasantry as a class. The glue of tradition and community binds it to face the harsh winters and outside oppressors. Yet the individualistic nature of land ownership is a constant source of conflict sending ripples across the community. It is a constant dance between local powerful individuals and the village interests as a whole.

While the main thread of the story is of a romantic nature, it is signalled very early in the film that there is much more to it. One of the main female matriarchs of Lipce tells us: “Love comes and goes. But the land stays”.

The interpersonal tragedy depicted would simply not happen if not for the question of land. Everyone (apart from Jagna, who is simply a commodity in the equation) is racing with each other to decide who will end up owning more.

In the end the question of land, the constant horse-trading, and the interests of the community must triumph over all else. When one man raises concern over the justice – or rather lack thereof – in village dealings, his words fall on deaf ears. Just or not, the village has decided; how can you think as an individual to go against it?

Gravediggers

And indeed an individual cannot change society, especially from within the microcosm of a peasant commune. Herein lies the historically progressive nature of the eradication of peasantry as a class, and its transformation into the proletariat.

By binding entire armies of workers together in socialised labour, capitalism has created its own gravediggers – a revolutionary class that has the power to turn the world upside down and sweep all the injustice of class society away.

The tragic story of Jagna, beleaguered by misogyny, ends with a village mob banishing her into the wilderness. Cast away and brutalised, she seems to finally be able to breathe freely, left naked in the rain.

This powerful scene ended with palpable tension in the air when I saw it at a small London cinema. Many fellow viewers were Polish women, having experienced their own share of oppression from the Catholic fundamentalists ruling their country.

Will they settle for being driven out of their homes by the backward mob? Or is there more to Jagna’s story since she was forced to leave the village for the town and join the ranks of the working class?

It wouldn’t be the first time that women sparked a revolution. And it won’t be the last.