The first major exhibition of its kind in some forty years, The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence is on show now at London’s V&A Museum, exploring the Mughal court’s century-long golden age of art.

In addition to providing visitors with an astounding collection of pieces – some rarely seen – the exhibition skilfully frames the artistic developments of this period through the reigns of three Mughal emperors: Akbar (r.1556-1605), Jahangir (r.1605-1627), and Shah Jahan (r.1628-1658).

These paint a fascinating picture of who the Mughals were, their values, and how they lived.

Opulence

The Mughal empire was incredibly wealthy, such that when England’s first ambassador wrote home in 1614, he described it as “the treasury of the world”.

Of course, this wealth was not acquired through a happy accident – the Mughals, as with every other Indian ruler prior to them, were despotic.

Yet, what is also a fact is that all the great Mughal rulers shared a support for the arts, religious tolerance, architecture, and literature (even Akbar, who could not read).

For a century, they put the empire’s immense wealth to use in the interest of developing these among the Mughal elite. As a result, this empire oversaw the creation of the most beautiful and stunning works of art that exist in all of pre-modern India.

The most famous of these is the architectural triumph of the Taj Mahal, which is rightfully given a prominent position in The Great Mughals.

First commissioned by Shah Jahan in 1631 and finally finished in 1653, in the 1980s it was designated a world heritage site as an outstanding example of Islamic art and Mughal architecture.

1657, Mughal court workshops. White

nephrite jade. © Victoria and Albert Museum,

London

But as the exhibition demonstrates, the Mughal golden age was not constrained to impressive buildings.

Tens of thousands of craftspeople, labourers, and designers from every corner of the empire’s significant territory contributed to exquisitely crafted artworks on every scale imaginable.

Their appreciation for symmetry and geometry, and their skills in working with marble, jade, textiles, and enamel were second to none.

One particularly notable piece in the exhibition is a nephrite jade wine cup, which was a gift for Emperor Shah Jahan and is carved into the shape of a ram’s head.

Working without any of the modern carving tools we have today, this immensely delicate, fluid, and detailed design was achieved by hand through a painstaking process of abrasion.

Art and culture

Such was the output of this period – and, tragically, such was the loss of many works – that naturally the exhibition can exhibit only a segment of the golden age.

Yet there are many insights to be gleaned from even these about Mughal society.

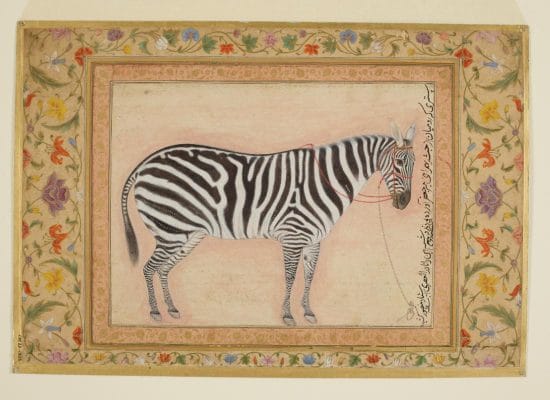

A number of the artworks revolve around animals and the natural world: a painting documenting a the gifting of a zebra, a satin hunting jacket embroidered in flora and fauna, and so on.

These pieces reflect not only the Mughal’s great philosophical and religious fascination with nature and humanity’s position at its head, but Mughal society’s day to day relationship with the natural world around them.

Jahangir, by Mansur, 1621, Mughal court

workshops. Opaque watercolour and gold on

paper © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Although they were larger in both size and population than any European city at the time, all of the Mughal empire’s great cities remained pre-industrial, based upon the activity of travelling merchants and craftspeople moving between city and countryside.

Yet, what is arguably most notable for an audience today is that in all the artwork in The Great Mughals there does not appear a touch of the religious intolerance seen in the region today.

‘A Muslim Pilgrim Learns a Lesson in Piety from a Brahman’, for example, was illustrated in Emperor Akbar’s court. It shows a Muslim pilgrim who has, inspired by the piety and prostrations of a Hindu he meets along the way, taken off his shoes to continue his journey barefoot.

Other paintings – spanning the reigns of Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan alike – depict the emperors’ adoption of the royal Hindu customs of the Indian Rajas, such as matching your weight in precious metals to distribute out to the poor.

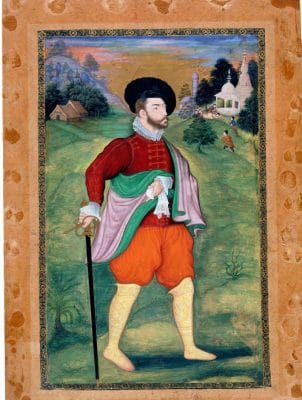

The outward-looking, ‘melting pot’ culture of the Mughals is also reflected in Jahangir’s French-designed throne; and in the merging of both European and Persian painting styles with the traditional Hindustani style that we can see taking place during this period.

However, as time passed, the Mughal empire was not just absorbing influences of surrounding cultures – it was (consciously or otherwise) utilising its own unified Mughal style to establish a Mughal identity.

As the exhibition highlights, by the 1650s floral designs (heavily inspired by the Taj Mahal) were spreading across the empire, taking root in all of the arts. This quickly supplanted, for example, the traditional regional motifs that had been used in inlaid cabinets produced in Gujarat and Sindh.

Decline

Due to its focus on the golden age of the Mughal empire, what the exhibition naturally does not explain in depth is the decline and fall of the Mughals. Nevertheless, the seeds of the empire’s destruction appear in its artwork.

One key factor was imperial overreach. While the reign of Emperor Akbar extended the empire enormously, at its height the Mughal empire spanned modern day India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

This could only be sustained for so long. During the reign of Shah Jahan’s son, Emperor Aurangzeb, the empire grew even more – and tensions that had been held back for some time were rising rapidly.

We can already see hints of these in one painting displayed in which Emperor Jahangir shoots the head Malik Amber, the Deccan de facto king who rose from slavery to become a mighty adversary.

Opaque watercolour and gold on paper. ©

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The presence of a painting of a turkey in The Great Mughal’s collection illustrates how the discovery of the Americas was having an impact all the way in India.

However, it also reveals how it was precisely not the Mughal merchants who were making these discoveries and extending the reach of their empire abroad, but European merchants and European powers.

Towards the end of the exhibition, Portuguese Jesuits merchants begin to appear in works. They are generally painted as minor figures at the bottom, with the Mughals at the top – clearly demonstrating what opinion the Mughals had of the European merchants!

Yet it was this growing mercantile trade at the periphery of the Empire – the developing thirst of primitive accumulation and the growing influence of European merchants at the empire’s hinterland – which would force the cracks in the Mughal empire wide open.

Legacy

Ultimately, it was these tensions within Mughal society – exacerbated and accelerated by the criminal role of the English East India Company in the region – which led the once-mighty Mughal dynasty along the path of a slow death.

As the empire declined, the many artists and craftsmen who had flocked to it began to move on to other, more prosperous courts.

In doing so, they brought with them the styles, traditions, and skills that had been developed within the Mughal court, disseminating them far and wide.

loan from The al-Sabah Collection, Dar al-

Athar al-Islamiyyah

Many of these (especially Shah Jahan’s favoured floral motifs) remain prominent in the designs of the Indian subcontinent and beyond today.

For those looking to experience the heights of pre-modern architecture, art, and culture, it is undeniable that these are to be found within the golden age of the Mughal Empire.

Such a concentration of works as can be seen in The Great Mughals is extremely rare to find, so we highly recommend visiting.

‘The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence’ is on show at the V&A South Kensington until 5 May 2025.