The latest series of ‘The Crown’ has provoked uproar amongst the establishment, for daring to depict the monarchy ‘warts and all’. By contrast, the Marxists welcome anything that exposes the reactionary reality of this decrepit institution.

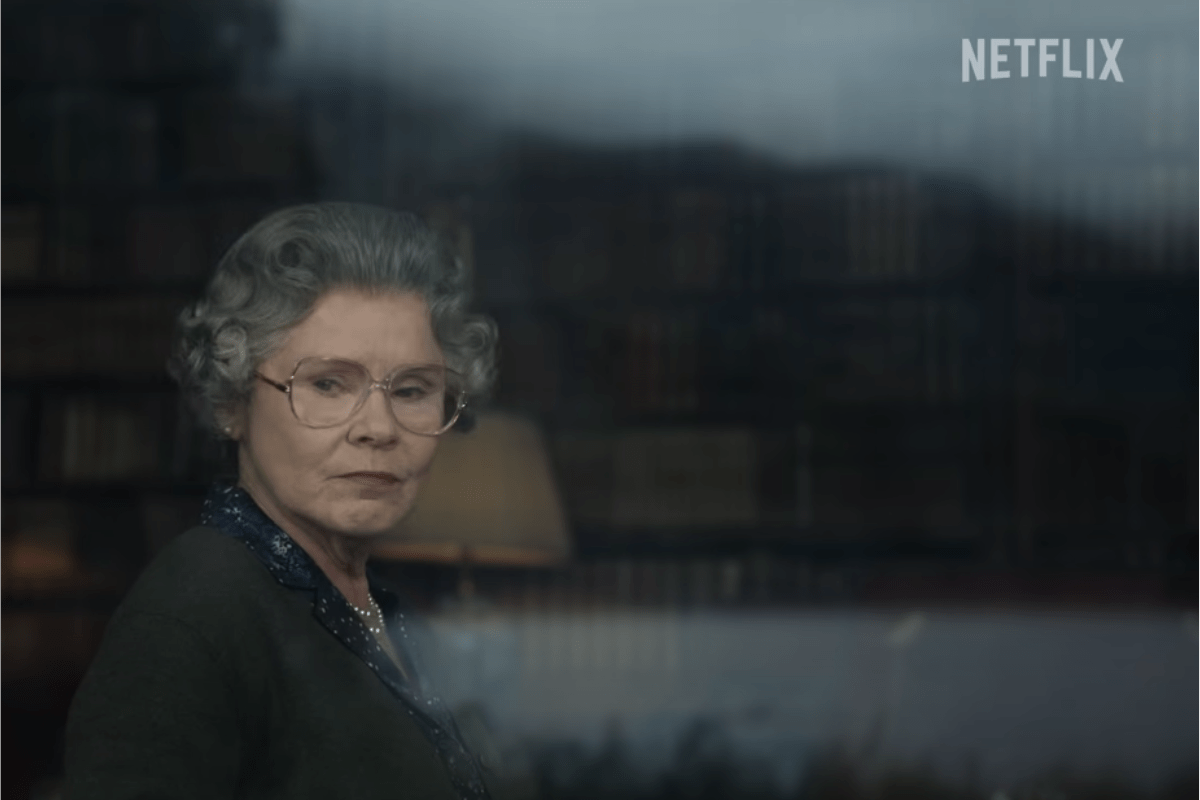

The establishment press has spared no effort to discredit the depiction of the Royal Family in series five of hit Netflix show The Crown.

As if on cue, these White Knights of the establishment have led the charge in defending the grace and decorum of the monarchs.

“So much of this series is very far from the truth,” bemoans The Times, summarising the show’s approach as: “if you don’t like the truth – if it doesn’t suit you – you simply make it up.”

Commenting on the series’ depiction of the Queen’s “Annus Horribilis” speech in 1992, The Telegraph remarks bitterly: “It is another example of the Netflix series distorting the truth, under the disclaimer (although, crucially, not a disclaimer displayed on screen) that it is a ‘drama’.”

Indeed, the demand for a disclaimer to be displayed on screen has become something of a rallying cry for critics of the series, reaching a crescendo in a sickeningly servile open letter by Dame Judi Dench in The Times, in which she writes:

“I fear that a significant number of viewers, particularly overseas, may take its version of history as being wholly true.

“The time has come for Netflix to reconsider [carrying a disclaimer] – for the sake of a family and a nation so recently bereaved, as a mark of respect to a sovereign who served her people so dutifully for 70 years, and to preserve its reputation in the eyes of its British subscribers.”

But far from a concern that viewers may be misled, the real issue that Dame Dench and her ilk have with The Crown is that it tells far too much truth about the inner workings of ‘The Firm’.

Charm

Of course, this disingenuous appeal to ‘truth’ is perfectly transparent. It is only logical that, to preserve the interests of an exploitative ruling clique, their real history, and continued rule today, must remain opaque, preferably hidden away by lock and key.

Of course, this disingenuous appeal to ‘truth’ is perfectly transparent. It is only logical that, to preserve the interests of an exploitative ruling clique, their real history, and continued rule today, must remain opaque, preferably hidden away by lock and key.

But don’t take our word for it. Famed constitutionalist Walter Bagehot admitted as much in his authoritative 19th-century work on the English Constitution (which, as depicted in The Crown, was used as education for the young Queen). He wrote:

“Above all things our royalty is to be reverenced, and if you begin to poke about it you cannot reverence it. When there is a select committee on the Queen, the charm of royalty will be gone. Its mystery is its life. We must not let in daylight upon magic.”

This latest series of The Crown is so unacceptable, then, precisely because it lets daylight in upon daylight. That is, it revisits a tumultuous period which, at the time, truly exposed the callous and degenerate nature of this institution and the individuals within it.

The Queen comes across as cold-blooded and out-of-touch, constantly invoking ‘duty’ and ‘God’s law’ to avoid engaging with her family emotionally, while simultaneously demanding public money to pay for a refurbishment of her superyacht.

Our present monarch, meanwhile, appears as a petulant son and a negligent husband. One particularly memorable incident involves Charles professing a desire to be Camilla Parker Bowles’ tampon.

Now, of course, who are we to judge a private conversation between lovers? But it does rather strip away the ostensible ‘charm’ of the monarchy.

Truth?

Unfortunately for the aforementioned stewards of truth and justice, these events (and many others besides) were widely reported on at the time, and known to be very much true.

Unfortunately for the aforementioned stewards of truth and justice, these events (and many others besides) were widely reported on at the time, and known to be very much true.

In fact, all-in-all, this series is a rather pedestrian retelling of events. The reality was far more shocking. Nothing is made, for example, of Prince Andrew’s friendship with notorious paedophile Jeffrey Epstein, which would have been blossoming at the time.

But even this conservative dramatisation, however, is too much for the representatives of the ruling class – who cling to the royalty, much like a small child clings to its favourite tattered and worn-out blanket.

The most damage to the institution, however, was surely done by its own increasingly bitter and fractured relationship with the much-loved Lady Diana Spencer.

People’s Princess

As Alan Woods explained, in an article written shortly after her death in 1997, Diana expressed a certain mood of the masses, simply through her unwillingness to accept the nature of the system she married into. She was open, empathetic, and easygoing; in direct contrast to the inhuman, detached way a royal is meant to act.

As Alan Woods explained, in an article written shortly after her death in 1997, Diana expressed a certain mood of the masses, simply through her unwillingness to accept the nature of the system she married into. She was open, empathetic, and easygoing; in direct contrast to the inhuman, detached way a royal is meant to act.

An illustrative interaction between Diana and the Duke of Edinburgh in the second episode reveals the class consciousness they sought to develop in her. The Duke tells her:

“You’re long past the point of thinking of us as a family. You understand, I think, it’s a system.

“And we can’t just air our grievances, or throw bombs in the air as in a normal family. Or we end up damaging something much bigger and something much more important: the system.”

By system, of course, he means the institution of the monarchy as ‘head of the nation’; a tool to cut across the class divide and provide stability to bourgeois rule.

But more than this, the monarchy is ultimately a reserve weapon for the ruling class in times of intense class struggle, and especially revolution. Pageantry and the myth of public ‘service’ are therefore used to build up and maintain this position.

This was the so-called ‘magic’ Bagehot sought to keep daylight out of. But Diana wanted to let the daylight in; and for this she was loved by the public, and loathed by the Royal Family.

Consequently, her death – set to be covered in series six – released an explosion of popular grief and anger which shocked the ruling class.

Clearly, this period, when the future of the monarchy was openly in doubt, is not one the British establishment is particularly keen to revisit. And that is why the establishment press has been churning out flimsy excuses to deride the series, such as the claim it is hurting the ‘feelings’ of the individuals it depicts.

Let the light in

Somewhere, the world’s smallest violin is playing for these royal parasites and their ‘feelings’. But if they are expecting this to connect with the mood of the masses, they should prepare to be sorely disappointed.

Somewhere, the world’s smallest violin is playing for these royal parasites and their ‘feelings’. But if they are expecting this to connect with the mood of the masses, they should prepare to be sorely disappointed.

It is true that the pomp and pageantry of the monarchy can cut across class lines at certain times. But during periods of stormy class struggle – such as we are living through now – most people could not care less about the flights or fancies of this or that Mountbatten.

And if it is distasteful to hurt the feelings of kings and queens, princes and princesses – what would it then be called to defend their gilded castles and sordid activities, in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis which has seen millions struggle to get food on the table, or keep a roof over their heads?

Ultimately, the establishment are outraged as the show shines a light on the decrepit institution that is the monarchy, precisely at a time when their ‘stabilising’ role is increasingly in need.

For Marxists, by contrast, all and any exposure of this rotten, reactionary institution is always welcome. May series six of The Crown offer more of the same.