Published in October of last year, at the height of the second wave in Britain, Grace Blakeley’s The Corona Crash provides an illuminating perspective on how the pandemic will change global capitalism in the years ahead.

To understand the capitalist system’s potential future, however, Blakeley correctly looks to the past. After all, as the author notes, and as the Marxists have pointed out previously, COVID-19 is not the ultimate cause of the current crisis. Capitalism was in a quagmire before the pandemic. And it will continue to stagnate and decline even after (if) the virus is vanquished.

“The severity of the pandemic-induced recession is at least in part a result of the pre-existing vulnerabilities of the global economy,” Blakeley asserts, highlighting the slow growth, ballooning debts, and increasing inequality seen worldwide in years prior to the coronavirus crisis.

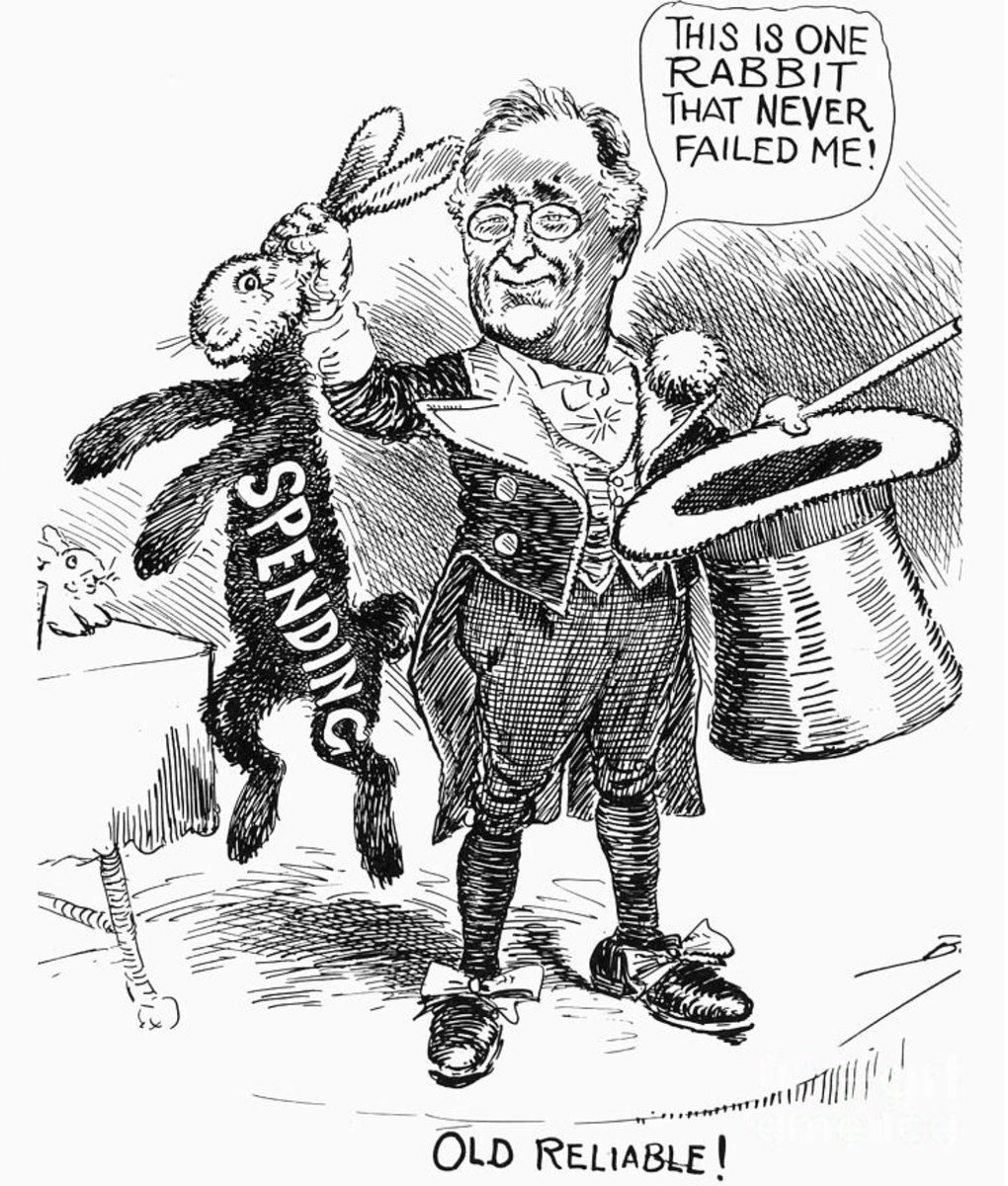

Blakeley, a prominent economic commentator on the Left, draws attention to the “unprecedented economic interventions” by governments and central banks seen over the last year – “not to help the most vulnerable through the crisis, but to save capitalism from itself.”

This is exactly the purpose of Keynesian policies, as we have explained elsewhere. Keynesianism is an economic doctrine designed to defend the interests of the capitalist class, not the working class; a (futile) attempt to manage the system and “save capitalism” from its own contradictions.

State monopoly capitalism

Blakeley astutely notes, however, that such life support from the state is nothing new. This was already present before the ‘corona crash’, in the form of quantitative easing and other ultra-loose monetary policies.

Blakeley astutely notes, however, that such life support from the state is nothing new. This was already present before the ‘corona crash’, in the form of quantitative easing and other ultra-loose monetary policies.

And throughout history, despite their supposed admiration of the ‘free market’, the capitalists have always looked to the state at the first sign of trouble – as was seen in 2008, when the major financial corporations, deemed ‘too big to fail’, were bailed out by governments across the world.

The result today, the author asserts, is that we in fact live in a system of “state monopoly capitalism”: one in which the boundaries between governments, the banks, and big business have become increasingly blurred; where wealth and production is ever-more concentrated; and where the capitalists, Blakeley remarks, “have collapsed into the arms of the state, and appear set to become wholly and permanently reliant on it”.

Planning – in whose interest?

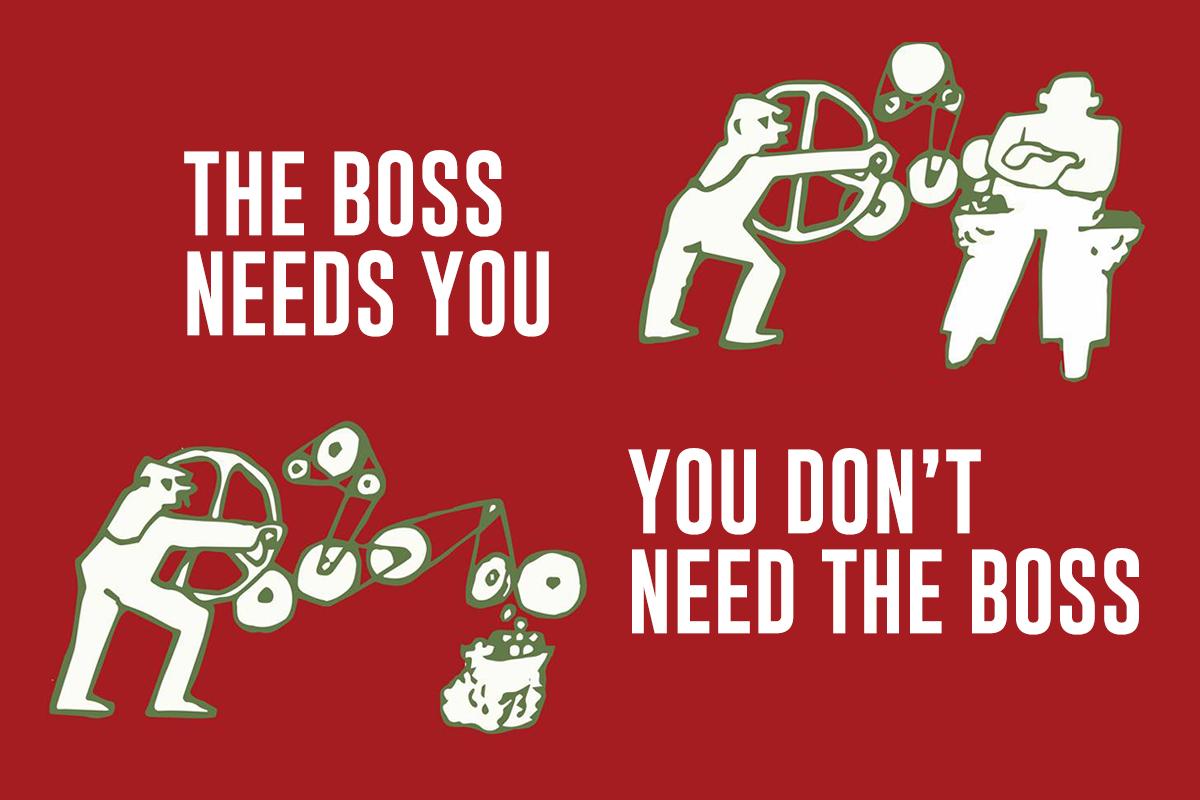

As we have also discussed previously , Blakeley highlights how this modern form of capitalism is essentially a planned economy, “except that the planning that is taking place is neither democratic nor rational”; planning not by-and-for the working class, but by “central bankers, senior politicians, and their advisors in big business and finance”.

, Blakeley highlights how this modern form of capitalism is essentially a planned economy, “except that the planning that is taking place is neither democratic nor rational”; planning not by-and-for the working class, but by “central bankers, senior politicians, and their advisors in big business and finance”.

The writer continues with a pertinent warning to the Left:

“We cannot fall into the trap…of believing that a quantitative increase in state activity somehow affects a qualitative shift from capitalism to socialism. Instead, we must concern ourselves with how state power is being used – and who is wielding it.”

Blakeley follows this with an extremely apt quotation from Lenin, in State and Revolution:

“The bourgeois reformist view that monopoly capitalism or state-monopoly capitalism is no longer capitalism, but can already be termed ‘state socialism’ or something of that sort, is a very widespread error…

“But however much of a plan they may create…we still remain under capitalism – capitalism, it is true, in its new stage, but still, unquestionably, capitalism.”

This reformist “error” is indeed “very widespread” – particularly so today in the left milieu that Blakeley and similar ‘trendy’ commentators inhabit.

Systemic crisis

Throughout her new book (in reality, an extended essay), Blakeley does a commendable job of largely avoiding the superficial reformist analysis that typically permeates such circles.

At the same time, she steers clear of the postmodernist view of history, as epitomised by the recent documentaries of Adam Curtis, which presents a disjointed ‘narrative’ of isolated events, ‘great’ individuals, and random historical ‘accidents’.

Instead, Blakeley connects the dots and draws out the economic and political processes that have led from the postwar boom, to the world crisis of the 1970s, to the financialisation of the 80s, to the globalisation of the 90s, to the 2008 slump, to the current ‘corona crash’.

Quoting Marx, for example, Blakeley explains how both concentration and crisis are inherent tendencies within capitalism; phenomena that result from the “immanent laws of capitalist production itself”; processes that logically arise from an economic system based on private ownership, competition, and production for profit.

Falling into the trap

Having come so far, however, the author unfortunately slips at the final – most important – hurdle, when it comes to outlining the way forward.

Having come so far, however, the author unfortunately slips at the final – most important – hurdle, when it comes to outlining the way forward.

Blakeley rightly points the finger at capitalism as a whole, and openly calls for socialism, asserting that:

“Socialism does not simply mean expanding the size of the capitalist state. Socialism means taking power away from the ruling classes – senior politicians, business owners, and financiers – and handing it back to the people.”

“In order to achieve this goal,” Blakeley continues, “it is not enough to demand a bigger state – the nature of the state, and of all our economic and political institutions, must be fundamentally transformed…”

But exactly what this goal looks like – and, most importantly, how we are to achieve it – is left hanging. Instead, the writer slips into vague formulations about “democratic public planning of economic activity” and “the people”, blaming “neoliberalism” and calling for a “Green New Deal”.

This latter demand, however, is an allusion to precisely the same Keynesian state-regulated capitalism that Blakeley earlier warns is a reformist “trap” that the Left must avoid.

Need for revolution

Instead of this woolly reformism, the Left needs to fight for clear and bold socialist policies. We must demand nationalisation of the ‘commanding heights of the economy’, to be run under workers’ control and management.

Above all, we must not be afraid to say the words that Blakeley and her self-conscious, vogue peers dare not utter: We must organise to overthrow capitalism. We need a revolution.