Hosted in a small community theatre on the Isle of Dogs, ‘Ten Days’ – a dramatic interpretation of John Reed’s famous book about the Russian Revolution, ‘10 Days That Shook the World’ – has enthralled audiences in London recently.

As the play notes, John Reed was an honest communist and defender of the October Revolution.

Observing the 1917 revolution first-hand, as a journalist for American socialist magazine The Masses, Reed considered it his revolutionary duty to detail the reality of this epoch-shattering year, which he correctly understood would face deep slander from the ruling classes and their mouthpieces.

This recent theatrical production captures the events leading up to the revolution, whilst managing to avoid many of the lies and myths that have been spread about this period.

Reality

Amongst academics and cultural theorists, two main interpretations on the function of art persist. The first sees theatre’s role as being a ‘mirror’, reflecting the real conditions around us. The second argues that theatre and other forms of art must be a ‘hammer’ with which to shape reality.

Amongst academics and cultural theorists, two main interpretations on the function of art persist. The first sees theatre’s role as being a ‘mirror’, reflecting the real conditions around us. The second argues that theatre and other forms of art must be a ‘hammer’ with which to shape reality.

Ten Days, written and directed by Mathew Jameson, utilises both of these devices to make a revolutionary argument: that the conditions of Britain today echo those of 1917 Russia; and that a revolutionary leadership is necessary to bring about socialism in our own lifetime.

The performance begins in February 1917, when women workers instigated protests that spread and grew into a mass revolt that overthrew the Tsarist regime.

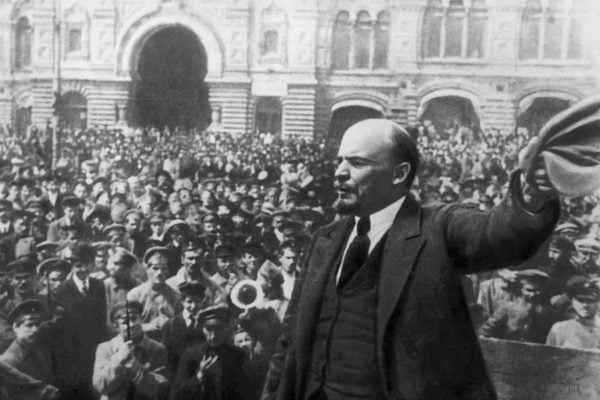

From here, the play follows these titanic events from the perspective of Vladimir Lenin, as he prepares the Bolsheviks to lead the working class to the seizure of power in Russia.

Parallels

This rendition of Reed’s writings clearly nods towards the current situation, with important historical figures played to resemble those of contemporary British politicians.

The mannerisms of Georgy Levov, for example, the first failed prime minister of the Provisional Government, mimic those of Boris Johnson. His successor, Alexander Kerensky, is also clearly intended to remind viewers of Rishi Sunak.

Both characters repeatedly offer platitudes about parliamentary democracy, whilst ignoring the demands of workers on the streets. Such bluster and hollow rhetoric will be all too familiar to audiences today.

The real nature of the Provisional Government is shown clearly. Kerensky and co. could not solve any of the problems faced by the Russian masses. Despite all the talk from these liberals and reformists, the dire conditions facing ordinary people only worsened.

In one scene, all the major political parties argue about why they should be elected, with each declaring their promises to the newly-freed people of post-Tsarist Russia. The questions from the crowd focus mainly on the First World War, which every representative either refuses to comment on or outright supports.

The parallels to the current conflict in Ukraine are clear: every mainstream party is either looking to drag out the war, making it more bloody and deadly, or cannot offer any answer to the horror and violence.

Lenin, by contrast, is able to appeal to the workers, peasants, and soldiers on the behalf of the Bolshiviks – proclaiming their demands to end the war, nationalise the land, and put all power into the hands of the exploited masses.

When challenged on whether any party can deliver these demands, he proudly states: “There is such a party!”

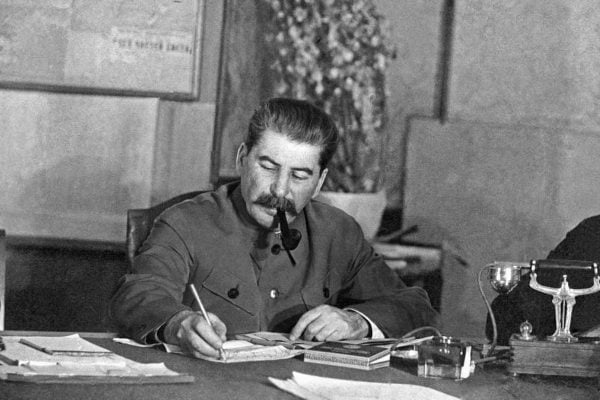

Stalin

One extremely accurate portrayal is that of Joseph Stalin, who for the majority of the play goes by the name of Koba, his Bolshevik pseudonym.

This consistent use of his party name seems to be a deliberate choice by the writers, leaving many wondering where Stalin is throughout the show’s scenes.

Koba is shown to be an utter mediocrity. He hardly makes a mark in central committee meetings, and spends most of his time making tea for Lenin, Kamenev, Zinoviev, and Krupskaya.

Koba is shown to be an utter mediocrity. He hardly makes a mark in central committee meetings, and spends most of his time making tea for Lenin, Kamenev, Zinoviev, and Krupskaya.

He has no lines until the very end. He does not participate in the revolution. And as the drama unfolds around him, it is clear that he is an intentionally forgettable figure.

After the triumph of the October insurrection, Koba is given a short speech – but is spoken over and drowned out by John Reed. The author explains that he only mentions Stalin at the very end of his book, where he conveys a “dry speech about national liberation”.

Although theatrical, this depiction accurately represents the real role that Stalin had in the events of 1917: an unimportant, peripheral one. In the words of Reed, he was little more than “a grey blur” in the revolution.

Many fictional works portray Stalin as a master manipulator. But this play is quick to point out the truth: that he was an uninspired, low-level opportunist, who came to power at the head of a bureaucratic caste in conditions of devastation and exhaustion.

Reed’s book was later banned in the Soviet Union. No doubt the bureaucracy considered it dangerous to remind workers of who had really led the revolution – and of the insignificant influence that Stalin had throughout 1917.

Lenin

On the other side, the play paints Lenin in the same light as many bourgeois historians do, showing him as disconnected from the masses.

On the other side, the play paints Lenin in the same light as many bourgeois historians do, showing him as disconnected from the masses.

In reality, however, Lenin’s role was invaluable. He embodied the revolutionary spirit of the workers and youth.

Within a party that held yearly elections, Lenin continually went unchallenged as leader. Bourgeois historians misinterpret this fact to suggest that he ruled by an iron fist, verbally berating anyone who dared to challenge his perspectives and proposals.

Lenin was no stranger to fighting for his ideas, however. He often had to argue his position through patient explanation, sometimes from a starting point of standing in a minority of one.

On this basis he built a cadre organisation, on the solid foundation of Marxist theory and methods. This allowed the Bolsheviks to successfully strike a chord with the Russian masses, and to lead the working class to power.

In the play, when Lenin introduces his April theses, his vital importance is revealed. He pushes the party away from a reformist line, denounces the new liberal government, and calls for a second – socialist – revolution.

Without Lenin returning and rearming the party, the Bolsheviks would have been blown off course. Without the Bolsheviks, however, Lenin would have just been one of many voices lost in the wind.

Without the leadership of the Bolsheviks, the October Revolution would have ended in bloody defeat for the masses. And without Lenin, the Bolsheviks would not have been equipped for the historic task of leading the working class to victory.

Revolution

Theatre, whether revolutionary or not, does not need to choose between being a ‘mirror’ or a ‘hammer’. This is a false dichotomy.

As Trotsky believed, the purpose of art should be to represent the truth. In doing so, the artist reveals not only the world as it is, in any epoch, but all of its contradictions also, showing the potential for how society could be.

In its greatest manifestations, therefore, art – including theatre – is both ‘hammer’ and ‘mirror’.

Ten Days, in this respect, accurately relates the truth of 1917 Russia, and of Britain today.

By looking back on the inspiring events of October, it points the way forward for workers and youth, showing what is to be done: the building of a revolutionary leadership, based on the example of Lenin, Trotsky, and the Bolsheviks.