The “Red Star Over Russia” exhibition, which opened at the Tate Modern earlier this month, is the latest in a number of exhibitions marking the 1917 Russian Revolution centenary. Whilst most of these exhibitions have trotted out the usual lazy, overused anti-Bolshevik cliches, this exhibition stands at a higher level. This is doubtless due in large part to the input from David King, whose collection – acquired by the Tate before he sadly passed away last year – comprises the majority of the material now on display.

Iconic images

Immediately on entering we are presented with an incredible array of propaganda posters dating from the period of explosive creativity that followed the October Revolution. These posters spoke to all nationalities, in all the languages of the former Tsarist empire – there was nothing of the Stalinist bureaucracy’s later policy of Russification. Rather the Bolshevik regime supported all symptoms of national and cultural awakening.

Through posters that crossed the threshold between mass media and high art, the Bolsheviks sought to raise before the masses the most important tasks facing the revolution. Front and centre was the question of bringing women out of their position of servitude and into sphere of running society (see for example, “Women! Take Part in the Elections to the Soviet!”). Other posters promoted literacy campaigns (“Literacy is the Path to Communism”) whilst others called for the defence of the young regime of workers’ democracy, through enlistment to the Red Army and Red Cavalry (“Join the Red Cavalry!” and of course El Lissitzky’s “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge”).

These visual monuments show us how the early Soviet regime not only conducted a heroic struggle against the White Armies, imperialism and the threat of famine, but also carried out an implacable struggle against all forms of cultural backwardness, mental slavery, and ignorance – in so doing, producing some of the most iconic images of the twentieth century. Whilst Trotsky’s famous “armoured train” brought technical specialists, literature and vital materials from one front to another, other trains were bringing cinema, literature, art and communist ideas to the most remote villages.

The revolution photographed

Alongside and interspersed with the posters and paintings on display, a whole number of other visual artefacts bring to life the events of the revolution, including photographs of the revolutionaries and even copies of the famous decrees declaring the Provisional Government deposed and the land nationalised.

Alongside and interspersed with the posters and paintings on display, a whole number of other visual artefacts bring to life the events of the revolution, including photographs of the revolutionaries and even copies of the famous decrees declaring the Provisional Government deposed and the land nationalised.

There are few attempts in the “Red Star Over Russia” exhibition to make the usual crass equation between the regime of workers democracy and the later regime of Stalinist totalitarianism. However, the break is also not made explicit, nor is any explanation given. However, through collections of rare footage, censored photos and crude caricatures, the role Trotsky played as co-leader of the revolution and his later effacement by Stalin, is clearly brought to the surface.

In one room a chronological panorama stretching from 1905 through to 1956 gives a telescopic history of Russia from the Tsarist period (with the front pages of fashionable Parisian magazines starring the Tsar’s family); through the 1905 revolution (see “Death stalking through Moscow”); the revolution of 1917; and on through the period of Stalinist degeneration.

Some of the most stomach churning images of this period include the photo of the signing of the Hitler-Stalin pact and, next to it, a poster produced after the invasion of the Soviet Union by Germany reading, “Britain and the Soviet Union: Comrades in Arms!” By the Second World War not a drop of the internationalism of the Revolution remained. Instead the war was presented as merely a patriotic war for the defence of the Fatherland.

From Bolshevism to Stalinism

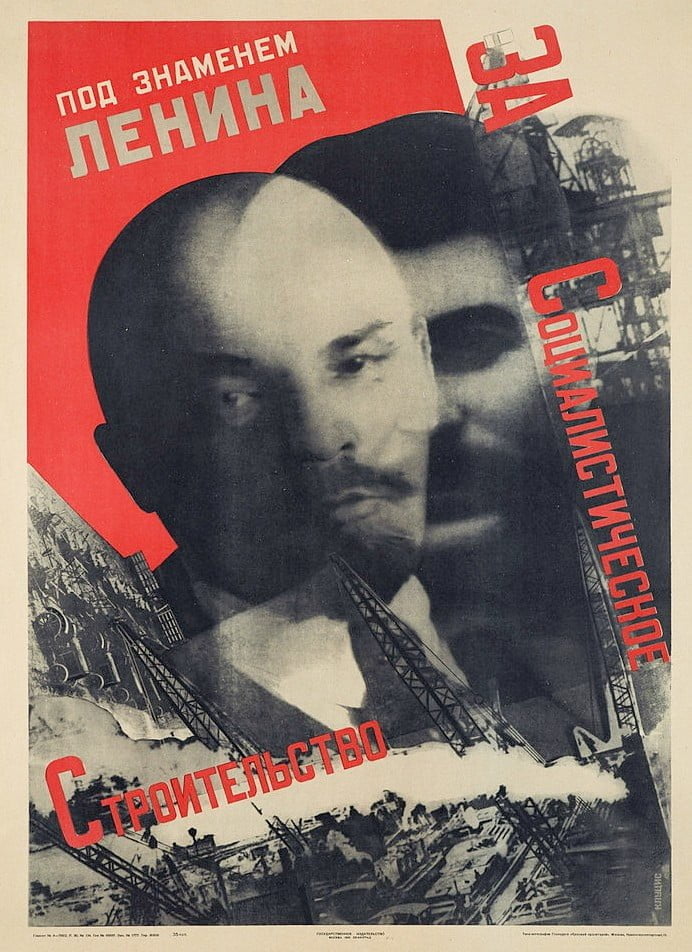

Some of the most stunning pieces are brought together in a room dedicated to the work of three of Russia’s most famous artistic couples: El Lissitzky and Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers; Rodchenko and Stepanova; and Gustav Klutsis and Valentina Kulagina. Here the zeal for progress in the artistic world is expressed through Rodchenko’s experimental photography, the powerful images of Lissitzky’s “Victory Over the Sun” and the bold, geometric images of Soviet workers by Kulagina. However, the tragedy with which this enthusiasm met when under the bureaucratic regime of Stalin is most painfully felt in the work of Klutsis.

Some of the most stunning pieces are brought together in a room dedicated to the work of three of Russia’s most famous artistic couples: El Lissitzky and Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers; Rodchenko and Stepanova; and Gustav Klutsis and Valentina Kulagina. Here the zeal for progress in the artistic world is expressed through Rodchenko’s experimental photography, the powerful images of Lissitzky’s “Victory Over the Sun” and the bold, geometric images of Soviet workers by Kulagina. However, the tragedy with which this enthusiasm met when under the bureaucratic regime of Stalin is most painfully felt in the work of Klutsis.

His bold photomontages glorified the progress of the Soviet Union and the role of Stalin. But they are not simple propaganda, mechanically churned out to suit the bureaucracy’s needs. There is a feeling of ambiguity. In “Building Socialism Under the Banner of Lenin”, a portrait of Lenin overlays a dark, shadowy image Stalin, emerging malignantly from the background. Meanwhile “The Brotherhood of All Working Classes of All the World’s Nationalities” centres on Stalin, and in front of him, adoring masses of workers. But these faces are strange and unnatural in their repose and raise the question: was Klutsis hinting at a critique of the regime?

Whilst there is no evidence to suggest that this is so, Klutsis’ fate is confirmed in the following room. In the same measure that the Bolshevik revolution sought to draw to itself the most brilliant artists of Russia, the counter-revolutionary bureaucracy sought to break their necks.

Along the walls are photographs of some of the most prominent victims of Stalin’s regime: Mayakovsky, the bard of the revolution, and Tukachevsky, the great military tactician. And in the centre of the room, a table of mugshots collected by King of victims of the purges. The primary target is obvious: to consolidate its rule the bureaucracy first had to liquidate Lenin’s party. But between mugshots of Trotskyists are anonymous students, and Gustav Klutsis himself.

Not content with clearing out its open enemies, the bureaucracy feared anyone who shone brighter than its own dull shades. At the end of the exhibition a number of mundane photos of men sat in offices amidst piles of papers: the bureaucrats of the OGPU, the hangmen in all their mediocrity.

The exhibition ends in a room playing Shostakovich’s masterpiece, the Eleventh Symphony (1957). Officially written to commemorate the suppression of the 1905 Revolution, it was in fact a condemnation of the crushing of the Hungarian uprising months earlier. Shostakovich, however, remained convinced of the ideals of the October Revolution. Rather it was the perversion of these ideals by the Stalinists that he subjected to withering artistic critique. In the same way, what stands condemned by this exhibition – despite all its flaws – is not Bolshevism but its antithesis, Stalinism.

Red Star Over Russia; Tate Modern, London. Until 18th February 2018.