Michelangelo: The Last Decades, running until 28 July, uses the extensive collection of Michelangelo’s sketches in the British Museum’s portfolio to showcase the skill of an artist whose work genuinely symbolised the high point of the Renaissance.

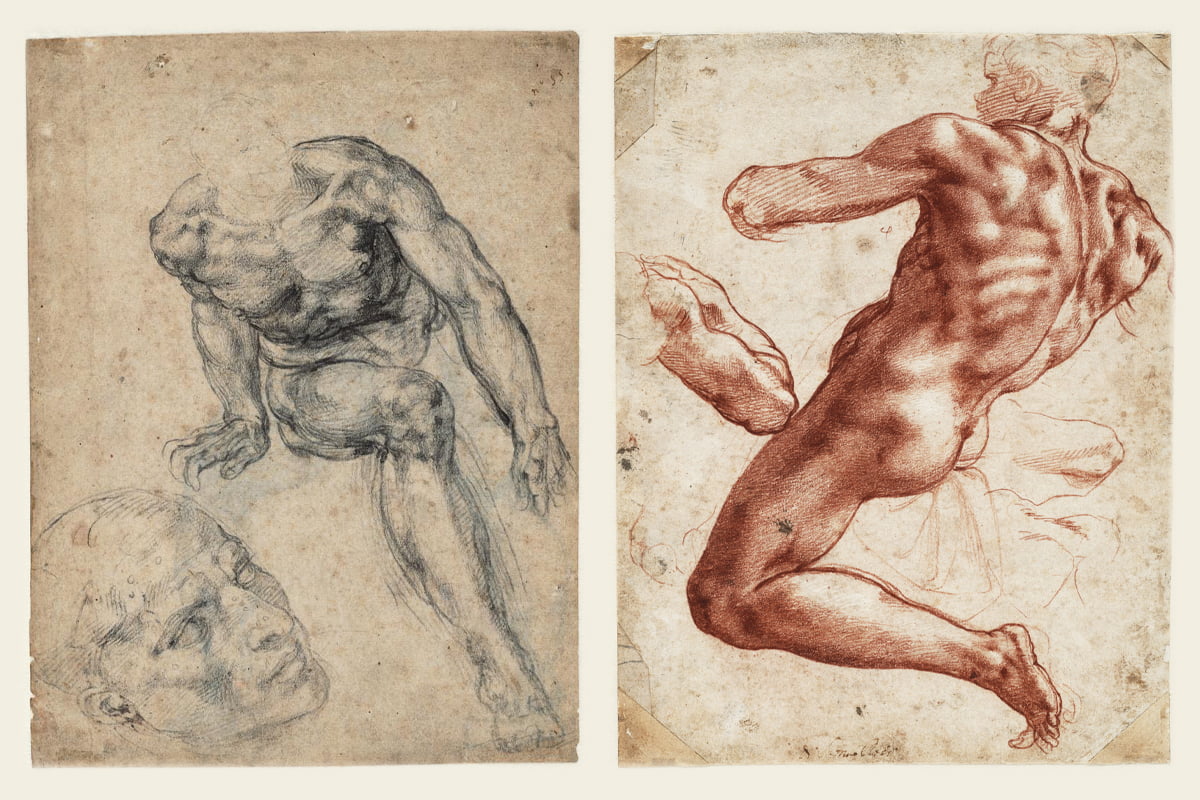

The remarkable feature of the exhibition is the clear attention to detail Michelangelo dedicates to capturing the body in motion, even in gigantic works like the Sistine Chapel paintings.

Michelangelo’s overwhelming focus on real bodies (which he even sometimes dissected to gain a better idea of their inner workings), set him aside from many other artists of his time, who relied on mathematical equations and proportions to portray a likeness.

Trotsky once explained that Michelangelo mastered capturing the human body because he appreciated its beauty lay not in idealised proportions, but in its living, organic form; constantly shifting, changing, and exerting energy and force.

“Classical sculpture,” Trotsky wrote, “reproduced the human body in a state of harmonious peace. Renaissance sculpture mastered the art of movement. But Michelangelo used movement to express the body’s harmony more vividly.”

Physicality and life

A few rooms draw attention to the personal relationships and faith of the artist, although in a sanitised form.

The exhibition goes into detail about Michelangelo’s chaste friendship with the poet Vittoria Collona, but glosses over his more physically-charged relationship with Tommaso Cavalieri, for example.

Equally, while it presents him as a man of faith, the exhibition does nothing to explain his Neoplatonic belief that it was the contemplation of beauty on Earth which could reveal to the observer aspects of the divine.

This is a shame, because it is very hard to understand Michelangelo’s art without this context.

For Michelangelo, divinity and ideal beauty was expressed in its most pure form through the human body, particularly the male physique, visible in Christ on the Cross and The Punishment of Tityus.

His sketches reveal his dedication to attaining as clear an understanding of the nude male form as possible, using this painstaking understanding of his subject matter to bring out an even more ‘ideal’ masculine form.

Michelangelo the artist never flinched from reality, but embraced it as wholeheartedly as possible. The same cannot be said of the portrayal of Michelangelo the man in the exhibition.

Peerless talent

Michelangelo’s peerless talent is nonetheless on display throughout.

Although sadly lacking any of his sculpture, the exhibition finishes on a high note with a room dedicated to the artists’ contemplation of mortality and illness in his old age.

One masterful sketch in this room, The Warwick Pietà, alone makes the exhibition worth visiting.

Though the sketch is very rough and lacks detail, each subject in the drawing has its own direction of travel: Christ’s form slumps backwards, pulled down by gravity; Mary twists away from him in the opposite direction; figures in the background reach out towards Christ, grasping for him whilst pushing Mary away.

This tiny piece, which is quite hard to find online, displays Michelangelo’s true mastery of not just movement, but force, and his ability to translate it on a page.

All of the artistic developments of the Renaissance, and in particular the rejection of the staid, lifeless traditionalism of the Middle Ages, are displayed by this exhibition, which makes it extremely worth a visit.

Michelangelo: The Last Decades is showing at the British Museum in London until 28 July.