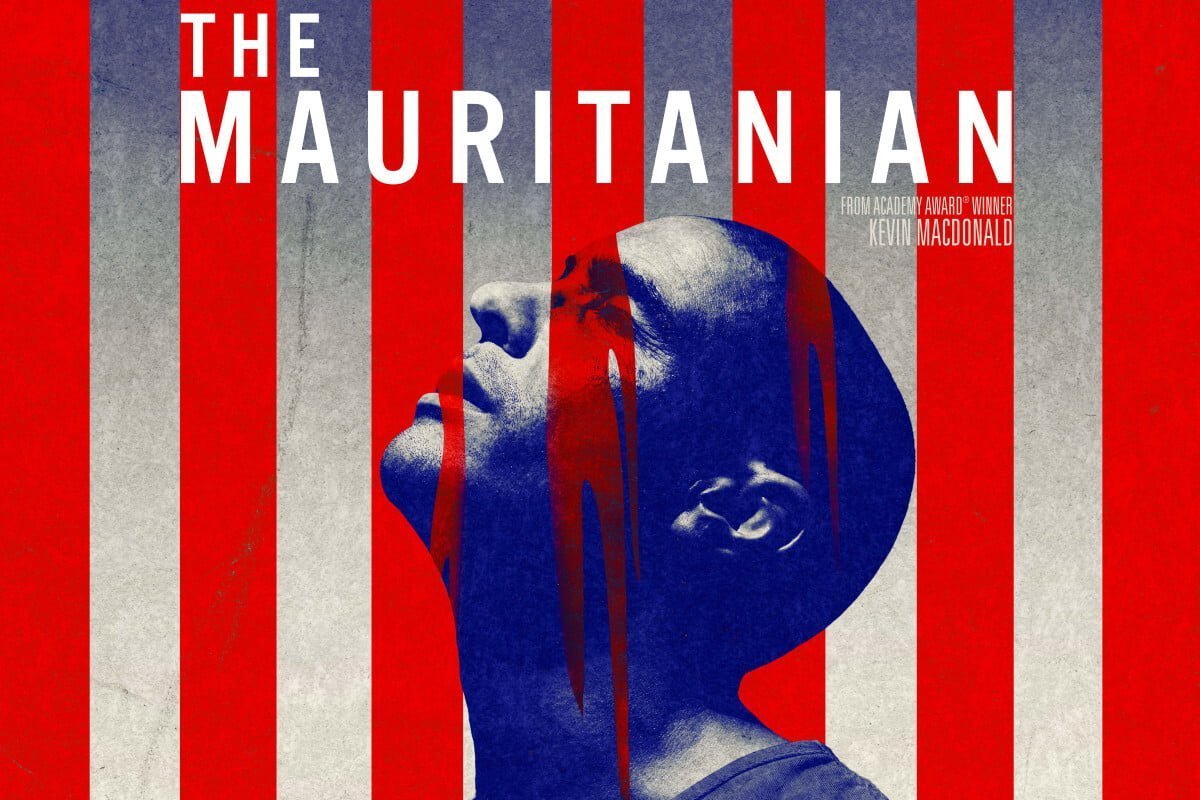

Recent release ‘The Mauritanian’ depicts the brutal treatment inflicted upon prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, as part of the so-called ‘War on Terror’. As this film shows, the biggest terrorist of them all is US imperialism and the capitalist state.

The BAFTA and Golden Globe nominated film ‘The Mauritanian’ tells the true story of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who was incarcerated in Guantanamo Bay for 14 years without charge.

Based on the best-selling book The Guantanamo Diary, the film is a graphic demonstration of the brutality of US imperialism, and the reprisals it enacted in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

Sinister secrets

The film begins in the joyous setting of a traditional Berber wedding, during which Mohamedou is approached by Mauritanian military officials for questioning. His mother anxiously waits on the sidelines as the cheroot-smoking official invites him for a ‘voluntary’ interview with the Americans. The next time we see him he is locked away in a Guantanamo cell.

This begins a legal drama in which Nancy Hollander (played by Jodie Foster), a successful human rights lawyer, and Lt Colonel Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch), acting for the prosecution, both navigate the murky corridors of US military practice.

Must watch. #TheMauritanian @TheMauritanian Superb actors, incredible story.

How many more like him are now incarcerated and tortured around the world? #justice #discrimination #torture #harassement #bullying #gitmo #Guantánamo pic.twitter.com/PKndRxqnu8

— Tweed&Tango (@TweedTango) April 5, 2021

Couch is initially spurred on by a thirst for ‘rough justice’, after he hears that Mohamedou ‘recruited’ the man who hijacked flight 175 and flew it into the south tower of the World Trade Centre. He is purposefully selected to prosecute because a close family friend was first officer on board flight 175.

The early stages of the film maintain a delicate poise as to the guilt or innocence of its protagonist. Mohamedou did train as a guerrilla fighter for Al-Qaeda in 1990 and 1992 – but this was in a war between the Afghanis and the Russians. As he points out, he was fighting on the same side as the Americans at the time. We should add that, at this time, the CIA would have been funding Al-Qaeda as well.

The film brilliantly demonstrates the sinister control of information by the CIA and other state departments, as both lawyers try desperately to get to the truth of the case.

Our expectations might have been that Hollander – acting for the defence – has to face these obstacles alone. But this is far from the truth. Clearly, at the heart of this investigation is a secret so dark that not even the army’s own military prosecutor is allowed to get near it.

Hell on earth

Throughout the film, Hollander and her associate Teri Duncan regularly visit Mohamedou at Guantanamo. This includes a surreal scene in the Guantanamo Gift Shop. The miles of tropical coastline are at odds with the hell the inmates face inside the facility walls.

So oppressive is the surveillance at ‘Gitmo’ that any sensitive information Mohamedou wants to pass on has to be written down in letter form before being sent to a Federal Secure Facility in Virginia for Hollander and Duncan to read.

At the centre of the film is the hunt for the Guantanamo MFRs – Memorandums For the Record – which contain the true nature of Mohamedou’s interrogation by Military Intelligence. The lawyers on both sides are constantly denied access to these until the CIA folds under pressure and releases the files.

What follows are truly shocking scenes of duress and torture. We hear that Donald Rumsfeld signed off on the use of ‘special measures’, proving a direct line between the government and the cruelty carried out.

Beatings; subjection to deafening noise; sexual humiliation; sleep deprivation; forced feeding; and waterboarding: these are just some of the inhumane methods used on the suspected terrorists.

They even threaten to have Mohamedou’s mother transported to Guantanamo to be raped by the other inmates. The revelations are so startling that it causes Couch to resign from the prosecution team, as both he and Hollander are left stunned by the level of brutality.

Rotten system

“Where I am from we know not to trust the police, we know the law is corrupt and the government uses fear to control us.” So testifies Mohamedou when his case finally reaches court.

He says that growing up, he “and so many people in the world” believed that America was different; that the law there was used to “protect people”. He learns the hard way that this is not the reality.

What is shown to us is that, under capitalism, the state and its institutions are merely a weapon in the hands of one class over another.

Perhaps the most shocking aspect of the film is that, even after Mohamedou wins his case for unlawful detention, he was still kept in prison for a further seven years after the Obama/Biden administration appealed the verdict. This is the true face of the man who has recently been elected President of the United States.

No justice

There are many courageous men and women in this film who fight tooth and nail for Mohamedou Slahi’s eventual release in October 2016; and none more so than Mohamedou himself. He is shown to be a warm and intelligent man, with an iron resolve.

But the real lesson of this film is not one of faith in ‘Habeas Corpus’, or even in human rights lawyers like Nancy Hollander. If anything, the fact that he was in jail for 14 years without even a shred of evidence proves the opposite: that for working people across the world, the criminal justice system is not a tool for their use.

After all, there have been countless thousands of political prisoners who have never found legal representation and who have rotted away in prison cells, or worse.

As Honore de Balzac says: “Laws are spider webs, through which the big flies pass and the little ones get caught.”

All working men and women of the world, if left isolated, are powerless before the state and its apparatus; they will get caught in the webs of their political-judicial system in the protection of class interests.

Repression and revolution

The only power capable of standing up to the capitalist state and sweeping it aside is the united, organised, and mobilised working class, armed with a radical programme to change society.

In March this year, it was reported that over 600 political prisoners were released in Myanmar after mass protests swept the country and weeks of general strikes.

Similarly in France 1789, the storming of the Bastille succeeded in releasing all the political prisoners who had been held there ‘at the king’s pleasure’.

In the course of revolution, we see the true potential of working people to change the balance of class forces and protect members of its own class. International solidarity campaigns are an important part of this fight, as we have seen with our own comrades in Pakistan.

Great performances, particularly from Tahar Rahim and Jodie Foster, make this a very watchable film. It is a visceral watch, and should act as a reminder about what happens when power is left in the hands of the capitalists, imperialists, and their state apparatus.