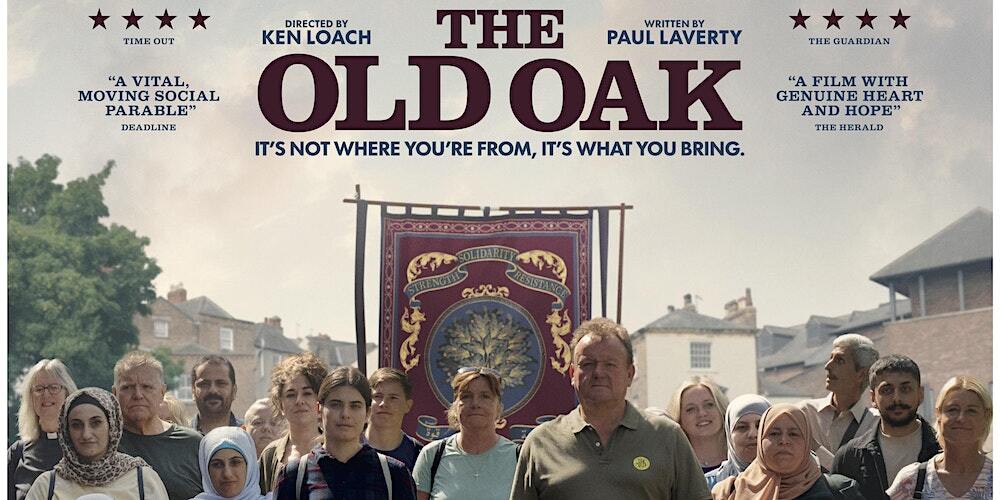

In his latest (and possibly last) film, The Old Oak, renowned director Ken Loach tells the story of refugees who are moved into housing in a declining former mining community in County Durham.

Set against a backdrop of poverty, racism, and war, the film explores how workers from different backgrounds can develop class solidarity, discovering that they have more in common with each other than originally thought.

Racism

The Old Oak opens with Yara, a photographer and Syrian refugee, arriving with her family to the English village. At first, she is met with hostility and racism from a number of the locals.

Left destitute by the legacy of Thatcherism, residents are shown to be resentful about the community becoming what they see as a “dumping ground” for asylum-seekers, due to its cheap housing, which has been bought up by investors to rent out.

With all the local amenities closed down, and services struggling to help local children who barely have enough to eat from day to day, the villagers quickly grow angry that these newly arrived refugees will be “taking what very little they already have”.

While set in 2016, the film reflects the divisive and reactionary ‘culture war’ narrative still pushed by the ruling class today, as it attempts to distract from its multiple crises. It examines the same tensions we see now as the government places refugees in deprived areas to save costs.

Solidarity

Yara does find support, however, in TJ, the owner of the eponymous local pub The Old Oak. Like the rest of the village, this watering hole has seen better days.

In the pub’s neglected function room, TJ shows Yara photographs revealing the village’s past, including pictures from the 1984 miners’ strike.

He describes how the defeat of the strike fractured the community. But he also recalls the solidarity people showed each other through these hard times.

Inspired by the idea that “when you eat together, you stick together”, TJ and Yara launch a plan to open a small, mutual-aid community kitchen out of the pub.

Although it is not all smooth sailing, due to some of the more resistant locals, the kitchen is set up.

Through sharing meals together, barriers are broken down between the refugees and the locals. They come to realise that – as working-class people – they face the same everyday struggles in the village; and that, by showing solidarity with one another, they are collectively stronger.

Hope

Loach has always had a good eye for the problems of everyday working-class life, and a talent for portraying these in simple yet very real and moving ways.

Loach has always had a good eye for the problems of everyday working-class life, and a talent for portraying these in simple yet very real and moving ways.

Unlike the bleak conclusions of some of his previous films, such as I, Daniel Blake and Sorry We Missed You, however, The Old Oak closes on a more hopeful note.

When news arrives that Yara’s father has been killed in Syria, their once-hostile neighbours gather to comfort the devastated family.

Yara and TJ’s project has not only helped to integrate the migrants into a formerly-divided community, but has laid the basis for them to truly “stick together” in rekindling the village’s collective spirit.

Revolution

When founding the community kitchen, TJ is very firm in insisting that what they are doing is “solidarity, not charity”.

It is certainly the case that there will never be enough charity to help all the 14.5 million people in Britain who were found to be living in poverty as of last year, or the refugees that arrive on the UK’s shores to escape war and poverty worldwide.

But it is the case that more than enough wealth exists in society to ensure that no one goes hungry, or lacks a decent home.

The only way we can ensure that the issues Ken Loach attempts to tackle are confined to the history books, not just lessened through solidarity and mutual aid, is through the expropriation of the big monopolies and capitalists: those who are responsible for this crisis.

This is only possible through a revolutionary programme that seeks to unite all workers and youth on a class basis, regardless of race, colour, or creed, in order to bring about the socialist transformation of society.