Alice Neel, born in 1900 in Pennsylvania, USA, was an American artist and self-proclaimed communist. Hot Off The Griddle, on show at the Barbican Art Gallery in London from 16 February to 21 May, is the biggest exhibition of her work in Britain to date.

The exhibition showcases a wide range of paintings and drawings, seeking to reflect how Neel sought to “catch life as it goes by, right hot off the griddle”. And despite some unusual curatorial choices, the art on display speaks for itself.

In the main, Neel showcases the lives of the working class and the oppressed – and often, their acts of resistance.

This exhibition also reveals a hidden history of the labour movement in the United States, presented to a London audience at a time when the cost-of-living crisis has pushed workers in Britain to take to the industrial front themselves.

Self-Portrait

The exhibition opens with a proud nude portrait, Self-Portrait (1980). This acts as our introduction to Neel, who sits naked, blushing as she holds onto her paintbrush. This was one of Neel’s last paintings and her first self portrait, produced at the age of 80.

The painting itself is vibrant, audacious, and a bit cheeky. But the curatorial choice to open with this piece seems misguided. It is a deceptive introduction: the majority of Neel’s art is not about herself. And though Neel painted numerous individuals, as the following rooms show, these were not about depicting people in isolation.

The essence of her practice was using the individual and specific to depict the collective and the general. Through this, her work builds an image of the lives, movements, and political mood of the working class in the US.

She often painted people she admired politically, as we see in Death of Mother Bloor (1951), a labour organiser and Communist. A lot of her art challenged the idea of who should sit for art, through depicting the lives of the poor and marginalised: from black intellectuals, to Puerto Rican immigrants and single mothers.

Figures

Although she found fame through the attention of ‘second wave’ feminists, undoubtedly Neel’s paintings and political perspective were predominantly influenced by the tumultuous times of 1930s America following the Great Depression.

Neel’s art is very much a product of this period. She was a beneficiary of the 1933 Public Works of Art Project: part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal Programme to counter widespread poverty and unemployment. This saw participating artists paid $26.88 a week on the expectation of producing art of sufficient quality every six weeks. The programme saved Neel from starvation.

This project recognised artists as workers, and even led to the formation of the Artist’s Union. As a result, many began to create politically conscious work, especially given the events taking place around them.

By 1935, Neel had joined the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and frequently attended demonstrations. Although she became frustrated by the bureaucracy of the CPUSA meetings, she was a lifelong supporter of the party and its professed ideals.

And so, as well as portraits, Neel made a number of paintings depicting demonstrations, pickets, and courtrooms throughout the 1930s. When grouped together, as done in this exhibition, these paintings build up an image of the labour movement in America and the political mood of the time.

History

The rich history of the US labour movement has been hidden and falsified by the ruling class. A common perception of the American working class today is that they are too chauvinistic or patriotic, with many people being unaware of the country’s rich revolutionary history – it was, after all, founded through revolution!

Neel’s paintings reintroduce this history to the viewer, expressively documenting this other side to history that is kept out of sight. The US in the 1930s was plagued by mass unemployment and a decline in real wages. But the working class did not take this lying down, and militant class struggle was on the rise.

In Magistrate’s Court (1936), we see Neel’s own experience in court after being arrested for picketing with the Artists’ Union. Works such as Uneeda Biscuit Strike (1936) and Support the Union (1937) also depict both police brutality against strikers and the collective organisation of the working class.

The piece Nazis Murder Jews (1936) also shows the anti-fascist side of the American labour movement. Neel was also involved in the anti-Nazi protest depicted, following the imposition of antisemitic laws by the Nazis in the Rhineland.

Whilst Neel’s paintings may be the work of just one artist, her work both came from and reflected the industrial tumult and political turbulence that characterised the 1930s, as American workers fought for change.

Defiant

Throughout the exhibition, there’s a clear sense that Neel was a defiant character; unafraid of going against the grain, not just in her personal life but politically too.

For example, Neel depicted and supported the struggle of black Americans, at a time when doing so as a white woman carried real risks. Save William McGee (1950) shows a demonstration calling for the freeing of Willie McGee, a black truck driver who was wrongfully convicted of the rape of a white woman in Mississippi.

Her bravery is also revealed in her portraits of leading members of the CPUSA during the height of the McCarthyite ‘Red Scare’ in the 1950s. At one point she was even investigated by the FBI. When two agents came to her home however, she simply offered to paint them as well!

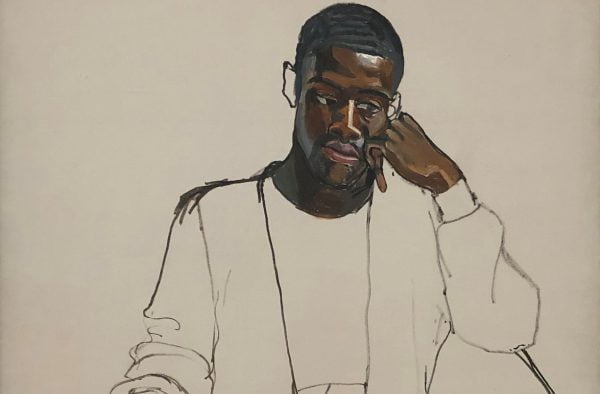

One particularly powerful piece is Black Draftee (1965), showing James Hunter: a black American who sat for a portrait just one week before he was drafted to fight in the Vietnam War.

The portrait is left unfinished as Hunter was gone before it could be completed. But this is also as a comment on how many draftees’ lives were tragically cut short as a result of the US’s imperialist meddling.

At a time when the Cold War saw propaganda pouring out of every cultural orifice that US imperialism had control of, the anti-war, anti-racist, and communist ideals underpinning Neel’s work were subversive.

Indeed, throughout the exhibition, what consistently shines through is her humanism. A lot of her work was made in a period when abstract expressionism was in vogue. This was a movement supported and encouraged by the CIA as a way of showcasing the apparent ‘freedom’ offered to artists by capitalism.

Neel instead chose to depict the real lives – both personal and political – and the plight of those downtrodden by American capitalism. This was not in the soulless fashion of Stalinist ‘socialist realism’, but with a style that carries across the life and character of those she painted.

Today

It is safe to say that Alice Neel was a true partisan of the downtrodden and oppressed. Although Neel did not have a coherent political philosophy as such (once describing herself as an “anarchic humanist”), there is no doubt she was an earnest fighter for a better society.

Art is a mirror that reflects society, with its prevalent styles and themes being reflective of big events; simultaneously influencing and being influenced by class struggle.

This exhibition proves this wonderfully. And the fact that Neel’s work is being exhibited today, in a world where once again workers are on the move internationally is significant.

We should celebrate the fact that a self-proclaimed communist and her politically conscious paintings are being exhibited.

But more importantly, we must pick up the banner of the struggles so excellently depicted by Neel, and honour the individuals who fought them. This cannot be accomplished through art alone, but only through socialist revolution – the taking control by the great majority of humanity over its destiny.