A recent four-part documentary by acclaimed left-wing director Raoul Peck examines the violent history of colonialism, showing capitalism’s bloody origins. It should be seen by all those looking to fight racism and imperialism today.

In 1944, Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin invented a new word: genocide. Within a few years it would be on everyone’s lips, as the full extent of Hitler’s Holocaust became known to all. But did the concept of genocide originate with Hitler and the Nazis?

This question is the starting point of Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck’s extraordinary and often stunning four-part documentary Exterminate All the Brutes (HBO/Sky), based on the Sven Lindqvist book of the same name.

The title comes from a line in Joseph Conrad’s famous 1899 novel Heart of Darkness: a grim study of colonialist depravity, which was later used by Francis Ford Coppolla as the basis for his Vietnam War epic Apocalypse Now (1979).

Conrad summed up colonial rule in the Belguim Congo in the words of the book’s narrator, Marlow:

“It was just robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a great scale…the conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.”

Extermination

Lindqvist’s book, published in 1992, makes the following point when talking about Hitler and genocide:

“…No one mentions the German extermination of the Herero people in southwest Africa…No one mentions the corresponding genocide by the French, the British, or the Americans, or that at the end of the 19th century.

“A major element of the European view of mankind was the conviction that ‘inferior races’ were by nature condemned to extinction: the true compassion of the superior races consisted in helping them on the way.”

Raoul Peck also knew that Lemkin, in coining the word genocide, was well aware of the long history of mass murder that had preceded Germany under the Nazis. It is this story that Peck sets out to show us.

Drama

The four-hour series – cut down from a massive 15 hours of film – has been described as ‘dense’ by many. Given all that it has to cover, this is quite understandable.

The four-hour series – cut down from a massive 15 hours of film – has been described as ‘dense’ by many. Given all that it has to cover, this is quite understandable.

Using photos, drawings, maps, animation, and the voice-over of Peck himself, the series sets out to show us the history of the real and brutal face of imperialism and colonial domination – from America to Africa and beyond.

The acclaimed director also makes use of clips from assorted Hollywood films to show how the true account of what happened has been constantly distorted by the media.

Of course, the main problem Peck faces in attempting such a project is the lack of actual film footage prior to the late 19th century.

Given that the key starting point of his history is the discovery of America in 1492, Peck’s solution is to dramatise key events with actors. This device certainly adds impact, as we see the full horrors of imperialist cruelty laid before us.

Actor Josh Hartnett plays a number of roles, acting as a kind of universal symbol of colonialism. Bizarrely at one point, Hartnett as an African colonialist dreams he is a 20th-century biker being beaten by black men in a kind of role reversal.

Peck wants us to understand the full impact of the violence used by imperialism, as it set to work conquering the world for profit and power. Using dramatisation enables Peck to largely achieve this.

‘Brutes’

Over the four episodes, Peck takes us from the extermination of the native tribes of America to the brutal slave plantations of the American South and the West Indies. He travels to Africa – the section on ‘the murky secret of rubber’ reminds us of Heart of Darkness again – and then to the destruction of Hiroshima.

Over the four episodes, Peck takes us from the extermination of the native tribes of America to the brutal slave plantations of the American South and the West Indies. He travels to Africa – the section on ‘the murky secret of rubber’ reminds us of Heart of Darkness again – and then to the destruction of Hiroshima.

This is not a linear journey. He brings us back to the same subjects again and again: in particular to Native American genocide and the establishment of slavery – the true origins of the US.

Peck constantly wants us to understand that such horrors are not just historical but have their counterparts today. Recent events in Africa, Latin America, and the Arab world provide ample evidence of this. The mass graves recently found in Canada also need to be considered in this context.

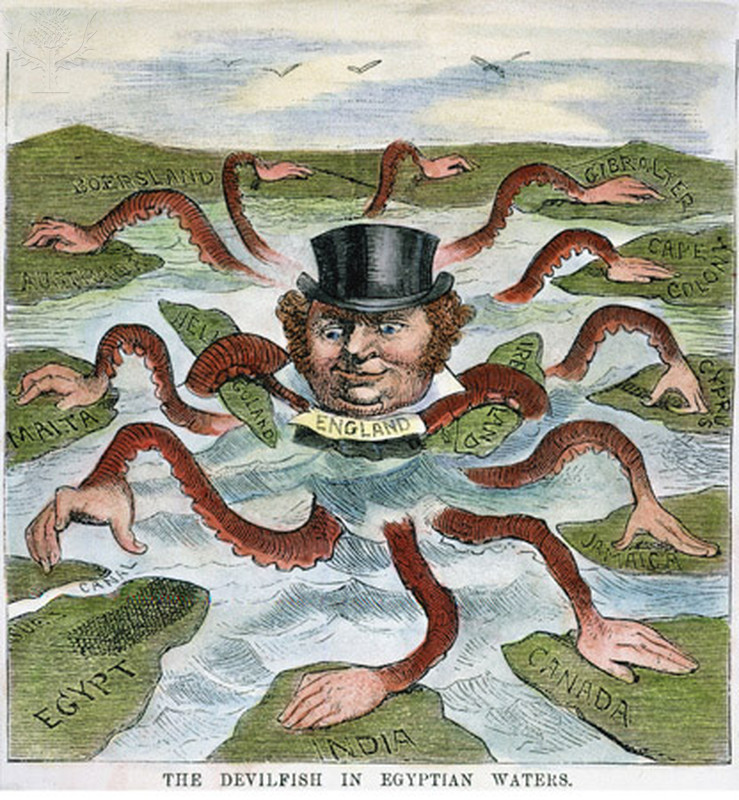

Peck draws out the way that racism was (and is) consistently used to justify the horrors of imperialism. The very concept of ‘white’ was often adjusted by 18th and 19th century politicians to explain why such brutality – indeed, outright extermination – was required.

At one point, even the Irish were considered to be non-white and therefore marked for purging, with Charles Kingsley calling them “chimpanzees”. Those who were marked for the most brutal exploitation were duly denied even their humanity by these men of enlightenment.

The so-called ‘civilised world’ constantly justified their horrific methods by explaining that the ‘lesser races’ – ‘the brutes’ –- were a hindrance to progress, and must be either removed or put in the service of the ‘advanced’ peoples.

Genocide was only tempered by the fact that dead men generate no profits. Mass murder, violence, and repression were the tools used to break revolt, crush opposition, and bend millions towards colonial domination and exploitation.

Justification

Colonial powers have always tried to justify their plunder by describing the peoples placed under such brutal domination as either ‘simple children’ or ‘savages’, depending on the degree of brutality to be applied.

The whips of the masters found their apologists in supposedly educated and ‘well-meaning’ politicians, writers, scientists, the clergy (of course), and many other such ‘enlightened’ and ‘educated’ men and women – all ready to expound the virtues of imperialist rule.

19th century scientists such as Robert Knox wrote of “the dark races” as having “a physical inferiority”; although he then added that he spoke “from extremely limited experience” (The Races of Man, 1850).

Knox did not think the colonial masses could be “civilised” and spoke instead of a “war of extermination”. Even Darwin spoke of “the savage races”.

According to Lindqvist’s book, A.R. Wallace – who helped discover the theory of evolution – would at a learned lecture in 1864 equate extermination of the ‘non-Europeans’ with natural selection; a form of weeding, in fact. This was how they explained away and justified the horrors of colonial reality.

Imperialism

Even today we see how great efforts are being made to defend the image of the British Empire, for example, as being somehow a force for good. The Tory government has been particularly keen to push this in schools and universities, all in the interests of balance they say.

Even today we see how great efforts are being made to defend the image of the British Empire, for example, as being somehow a force for good. The Tory government has been particularly keen to push this in schools and universities, all in the interests of balance they say.

The descendents of those who suffered under the lash of the colonial lords – in India, Africa, Egypt and the West Indies – might like to compare what these reactionary elements are saying with what Raoul Peck’s series has to show them.

The racism seen today has its origins in the rise of empire and the imperialist squabble for profitable empires to establish and rule over.

It is telling that Karl Marx, towards the end of Capital volume one, covers this very point when describing how capitalism in general, and colonial imperialism in particular, uses violence and oppression to expand its empires and rule over the peoples of the world.

Once the Great Powers (as they liked to call themselves) saw how much loot was within their grasp, then nothing was ruled out.

Resistance

Peck is keen for us not only to learn the real history of imperialism – “civilisation, colonisation, extermination” – but also to understand that the only way it can be fought is by resistance. For Peck, the Haitian slave revolt of 1791 is a key source of inspiration; a critical element in the abolition of slavery.

Raoul Peck’s epic story is one that deserves to be seen. Often shocking, sometimes graphically so, it challenges the line of all those establishment apologists who somehow claim that colonial rule was ‘beneficial’.

As the Chartists put it long ago when writing about the British empire: “On its colonies the sun never sets and the blood never dries.” (Ernst Jones, 1851)

To this can be added the imperialists of the US, France, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Germany… on and on.

Peck told a Guardian journalist this spring: “It’s not knowledge we lack. What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and to draw conclusions.”

Although the series never develops this, we must do so. Imperialism and colonial domination are just the most reprehensible features of the capitalist system – then and now. Only the socialist transformation of society can truly bring an end to the dark heart of imperialism.