The USA is no stranger to war, as the preeminent imperialist power for the last century. But as well as its sordid, murderous past, it has a revolutionary history as well.

The War of Independence in 1776-83 and the American Civil War of 1861-65 were, in effect, two revolutionary wars: first against British colonialism, and second against the slave-owning Southern plantocracy.

Today, the global crisis of capitalism has again placed wars and revolutions on the order of the day. Workers and youth in the USA have experienced over a decade of crisis. And the American ruling class is increasingly nervous that social polarisation could erupt into armed conflict.

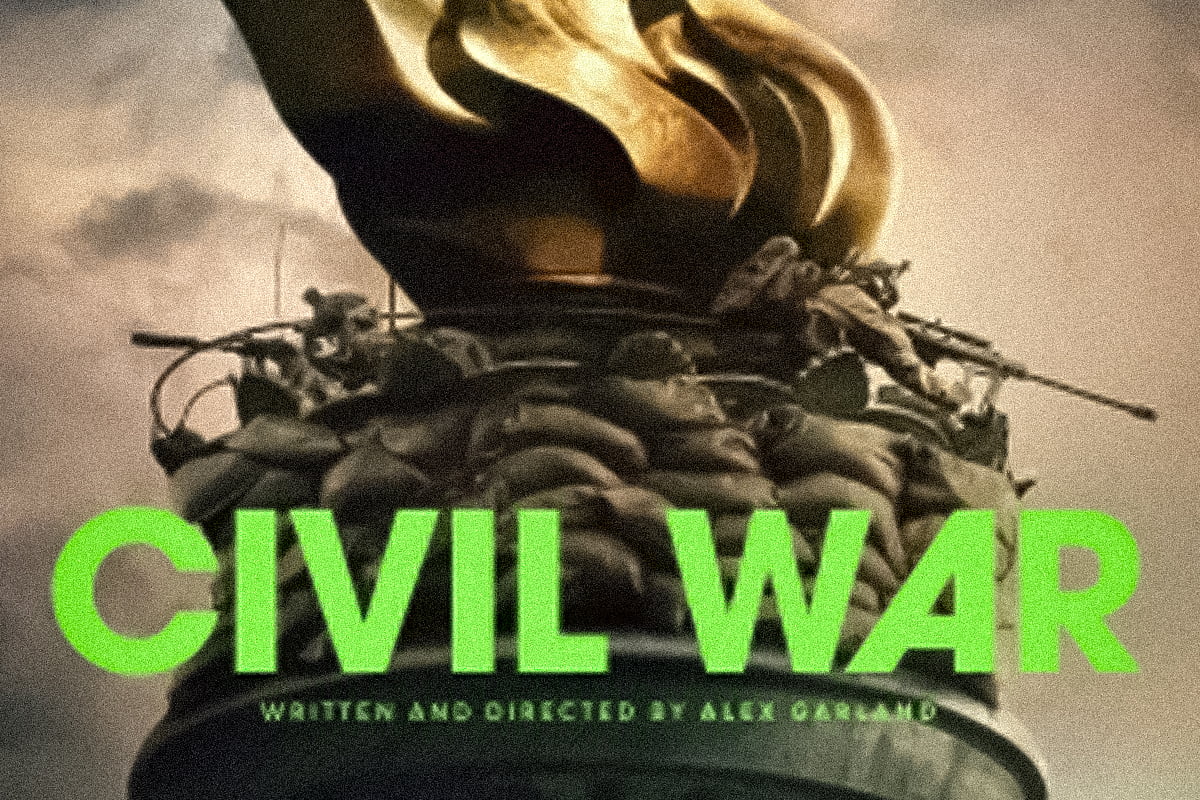

Against this backdrop, with profound and seismic shifts taking place across the world, writer and director Alex Garland’s depiction of a future US civil war appears timely and prescient.

Blurred battlelines

Civil War follows a quartet of journalists travelling across the USA, through combat zones, to interview the President, hiding in the White House.

Several ‘succession’ states are battling against the US government. But it is never explained why or how the conflict began, or what it’s about.

There are hints that the President is a Trumpian figure. And there are vague references to an ‘Antifa Massacre’ and the ‘Portland Maoists’. But these allusions aren’t fleshed out, and neither is their role in the war.

Art should be judged on its own terms, and not necessarily criticised for any lack of class analysis. As is often stated, however, quoting Prussian military theorist Clausewitz, war is the continuation of politics by other means.

It is therefore a missed opportunity that Civil War actively goes out of its way to avoid offering any explicitly political content, as this could have provided a richer, more meaningful and insightful story.

The high point of the film, for example, is a tense scene where the protagonists encounter a group of armed men burying dead bodies in a mass grave.

One of the men questions the journalists: “Are you American?”; “What kind of Americans are you?” And they plead in reply that they are plain, old “Americans”, as they struggle to maintain their neutrality.

It’s clear that the inquisitor is a nationalist. But it’s not actually evident which side of the war he is on. And without knowing his motivation or interests, the potential ramifications for the characters are muddied.

Realist art, by contrast, benefits from reflecting and bringing out the contradictions inherent in class society.

‘Neutrality’

The focus of the film is on the journalists and their attempts to document the war through photography.

They drive north to Washington DC in their minivan, stamped with ‘PRESS’ on all sides. At each checkpoint, camp, or group they come across, they present their press badges, as if these are an ‘access all areas’ pass.

The reporters are shown as being neutral in the conflict, almost cynical about its brutal reality.

Lee Miller (Kirsten Dunst) is a famous, veteran war photojournalist, admired by the group’s fledgling member, Jesse (Cailee Spaeny). Nevertheless, the impact of the horrors they witness and experience begin to weigh down on Lee, while they harden Jesse.

By purposefully omitting the political character of the civil war, Garland intends to portray journalists as the real victims – as liberal journalists ‘just trying to do their jobs’.

But this message misses the mark. In Gaza, for example, Palestinian journalists attempting to tell the truth have been murdered by the Israeli Defence Forces. Meanwhile, western media outlets have acted as propagandistic mouthpieces for the imperialists. The idea of ‘neutrality’ in this context is a farce.

Indeed, there is a certain irony when one of the journalists criticises a clothes shop worker for “trying to stay out of the war” by trying to go about their business as normal, while snipers sit upon roofs along the high street.

The reporters, themselves, do their utmost to document the war without getting their hands dirty, by refusing to take sides and by feigning a naive, fictional impartiality.

In the words of the late anti-imperialist documentarian John Pilger, however: “It is not enough for journalists to see themselves as mere messengers, without understanding the hidden agendas of the message and the myths that surround it.”

And the same is true for cinema. By refusing to take a position, just like the reporting of the ‘neutral’ journalists in this film, Garland’s latest feature lacks any real substance or meaning.

There is much more that could be said about Civil War. But in the absence of any genuine political content, we shall end with this: if you like big explosions, gunfire, tanks, helicopters, and graphic scenes of the war dead, then this movie is right up your street.