Danny Boyle and Alex Garland’s 28 Years Later is a fantastically crafted and creative piece of cinema; a faithful and refreshing take on sequels; and a genuinely moving coming-of-age story.

Yet it has received a surprisingly mixed reaction amongst audiences for its eclectic and unconventional approach.

Granted, there is a lot to take in.

From the terrifying Eisentien-inspired montages, to the heartfelt reflection on death that turns audience expectations on their head, to the post-ironic Jimmy Saville Teletubbies ninja cult (you’ll see…)

Anyone expecting a run-of-the-mill Zom-Com action flick is bound to be caught off guard. But this first stop in the franchise’s final trilogy certainly lives up to the reputation of its cult-classic inception.

28 Years Later drops us back into the world of 28 Days Later (2002) – now finally available online on BBC iPlayer – almost three decades after the outbreak of ‘Rage Virus’.

This highly contagious virus transforms the infected into aggressive, zombie-like killing machines. The subsequent pandemic rapidly led to the breakdown of society.

In the decades since, the virus has been eradicated in continental Europe, but not in Britain, which remains in indefinite quarantine from the rest of the world, in a state which can only be described as barbarism.

We follow Spike (Alfie Williams), a 12 year-old boy who lives in a survivor commune on the secluded ‘Holy Island’ of Lindisfarne off the Northumberland coast.

A sureshot archer, Spike is due to complete the commune’s coming-of-age ritual a few years early, on the insistence of his father, Jaime (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). The two venture to the infected mainland to make his first kill.

Montage

28 Years Later does not ease the viewer in – it taps into some of the greatest cinematic montage techniques to create a sense of tension from the start.

Blending film and archive footage together, we cut between shots of our protagonists, war scenes from Henry V (1989), and too-close-for-comfort shots of the infected. Captured with a red night-vision filter, in these shots their eyes glow and their skin seems all the more withered.

Alongside these claustrophobic montages, the film is not exactly subtle in its contrasting of the behaviour of humanity and the infected.

On Lindisfarne we watch as Spike’s mother Isla (Jodie Comer), bed-bound and succumbing to an unknown illness enters a violent fit of confusion. Resembling one of the infected, the blurred line between the Rage of the virus and the rage of humanity is brought to the fore.

Likewise, during their exhibition to the mainland, we watch as Jaime erratically swings between fatherly pride and guidance, and a father’s stern and authoritative anger – an anger as unpredictable as any infected.

Editing

The editing around Jaime and Spike lacks “motivation”, to use the technical term; what we see on the screen is not always necessary, and does not always carry the story forward.

This would be a mistake in most films, but herein lies the excellence – the horror is no longer predictable, it’s not what you can see, but what you can’t!

28 Years Later certainly understands spectacle too.

When Spike bags his first kill, and when Jaime relishes the thrill of playing sentinel, every single fatal shot receives a glorious, Matrix-style 360° pan around, letting you take in the gore and brutality in a very gamified way.

This provides a little relief from the tension of the close montages, but also reflects the decades that have passed since the terror of the first Rage Virus waves.

Living in a steady game of cat-and-mouse between humans and infected, though it may be horrifying and bear fatal results, the survivors necessarily frame it as a game.

Emotion

Each of the film’s four acts has a distinct tone and adjusts its artistic choices accordingly.

The first act is its most horrifying, returning us to the world of 28 Days Later and slowly acclimating us to this new way of life.

The second act uses the same editing tricks around “motivation”, packing a sometimes-overwhelming amount of information into each shot. But this time, it’s not to communicate fear for survival, but to reflect the emotional deluge we see Spike go through in the aftermath of his mainland adventure.

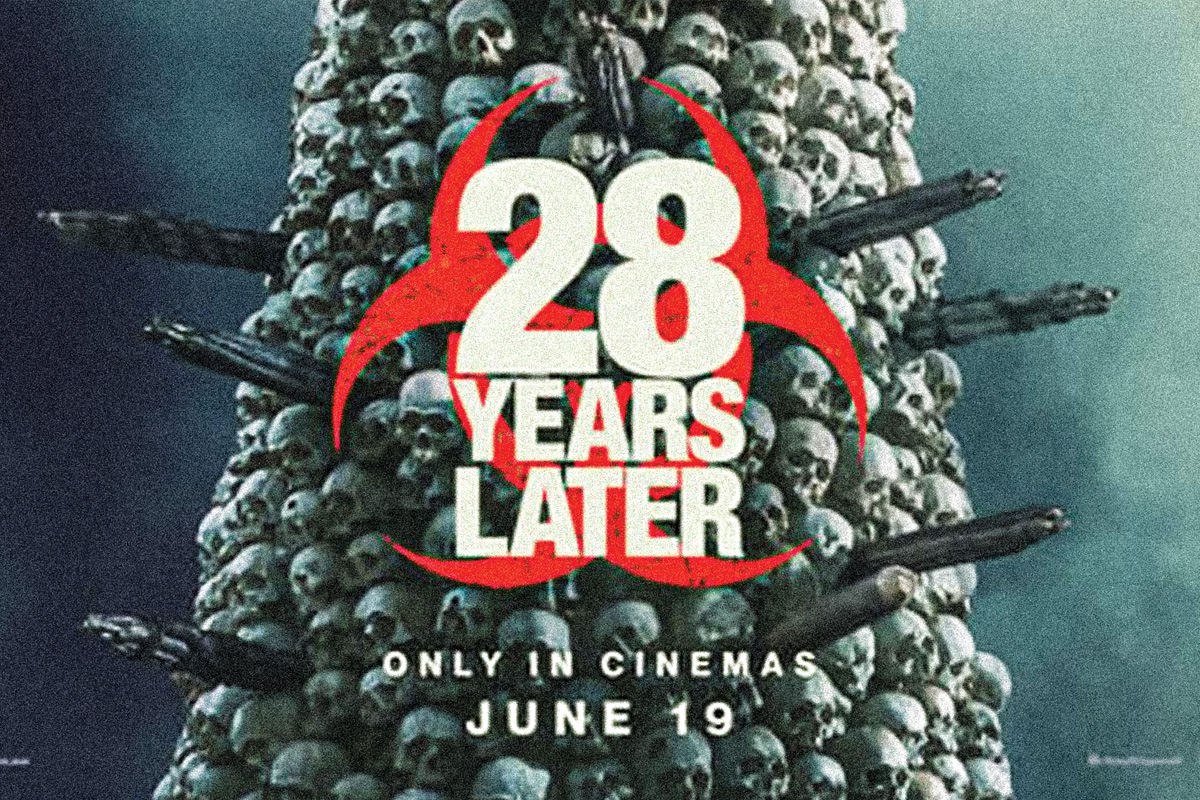

The final act is the most heartfelt of all, completely inverting what might be expected by audiences from the trailers – the towers of skulls, “some [kinds of death] are better than others” all take on new meaning.

And then comes the end, completing this perversion of our expectations, setting up a whole new set of stakes for the sequel, due to be released in January 2026.

If 28 Days Later was 50 percent a love story, 28 Years Later is 50 percent a coming of age story – with both being a quarter a horror movie and an examination of humanity apiece, too. The grand return to the world of 28 Days Later is not to be missed!

‘28 Years Later’ is showing in cinemas now.