As in any country, the ruling class in Ireland have distorted their history to disguise the role of the revolutionary masses. In Resistance and Rebellion, by RTE, the revolutionary role of James Connolly and the Irish masses are obscurred.

Though on its own a well-told and gripping thriller, RTE’s TV series Resistance, and to a lesser extent its predecessor Rebellion, perpetuate the same old myths.

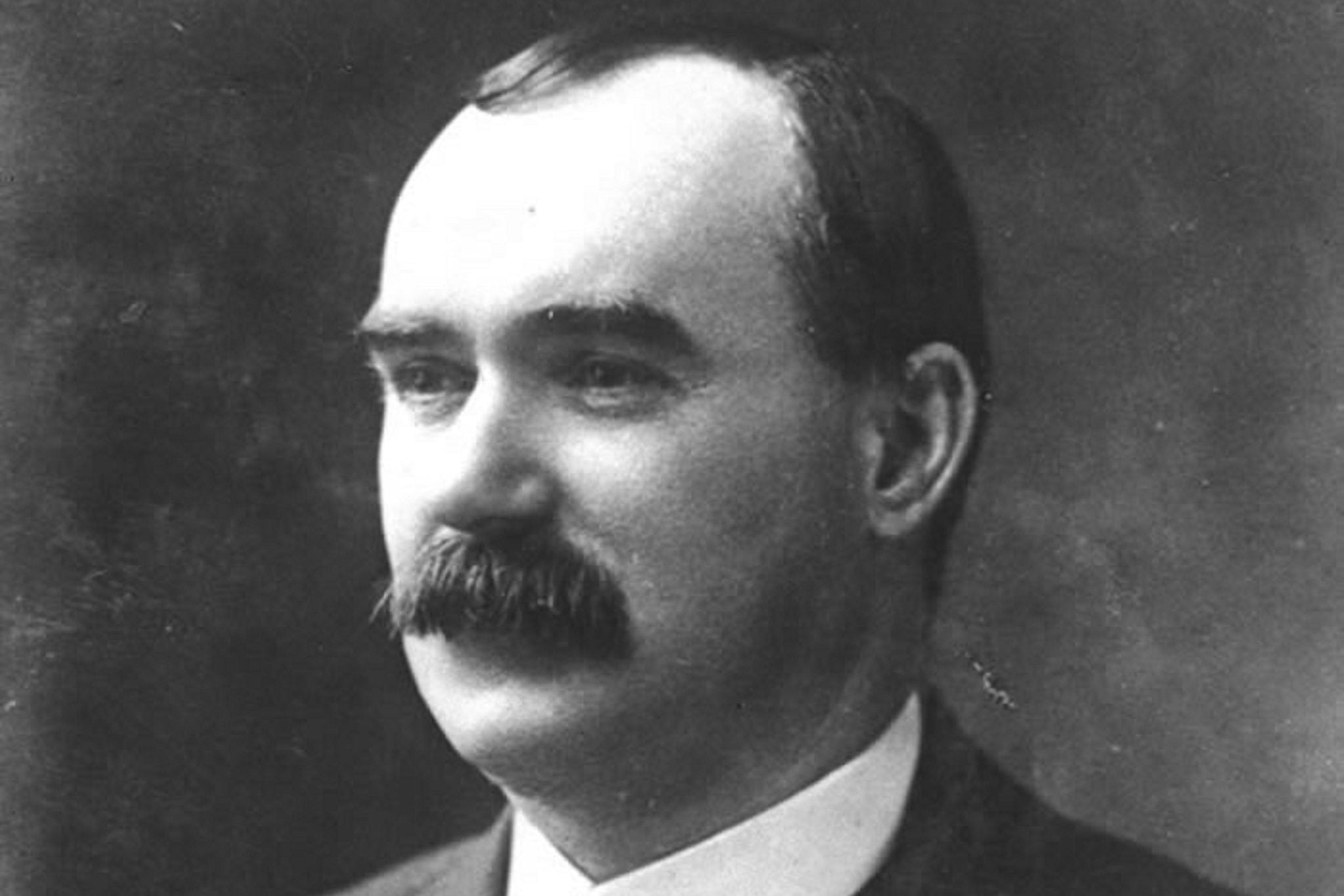

The great Irish Marxist revolutionary, James Connolly once declared that were history an accurate account of events, most of its pages would be filled with the struggles of the masses. Instead, history in the hands of the ruling class distorts and demonises the majority of our class whenever they move into struggle.

This is certainly the case with Ireland’s celebration of the 100th anniversary of the start of its War of Independence. The Irish ruling class, along with its counterparts in Britain, since the declaration of the Free State in 1922, have portrayed this period as a nationalist guerrilla struggle, led by Sinn Fein and the Irish Republican Army (IRA), who through small groups of armed men in Dublin and other major cities, forced British imperialism to the negotiating table and brought about Irish freedom. This narrative is heavily reflected in the conception and creation of the series Resistance, produced by RTE (Ireland’s state broadcaster) to mark the anniversary early this year.

Writing out the workers

The series mostly focuses on members of Dublin IRA leader Michael Collins’ famous ‘squad’, a counter-intelligence organisation created to assassinate the agents of British imperialism in the city. The aim of the series, according to producer Catherine McGee was to look at ‘what it was like to be caught up in events at the time’. Resistance fails in this in almost every way. Following the line set by the ruling class, it fundamentally denies the role of the Irish masses in their own history.

The series mostly focuses on members of Dublin IRA leader Michael Collins’ famous ‘squad’, a counter-intelligence organisation created to assassinate the agents of British imperialism in the city. The aim of the series, according to producer Catherine McGee was to look at ‘what it was like to be caught up in events at the time’. Resistance fails in this in almost every way. Following the line set by the ruling class, it fundamentally denies the role of the Irish masses in their own history.

The end of WW1, that great imperialist slaughter, saw a wave of revolutions, starting with the triumph of the Russian working class in 1917, sweep across Europe. In every country, the proletariat began to shake its chains and pose the question of power. Ireland was no exception and the War of Independence would see a revolution emerge which terrified the ruling class of Britain and its Irish counterparts.

Trotsky defined a revolution as a period when the masses overcome the barriers traditionally holding them back from the political stage and begin to take control of their own destinies. Nowhere was this clearer than in Ireland. April 1918 saw a general strike sweep the island as the proletariat fought against conscription and triumphed.

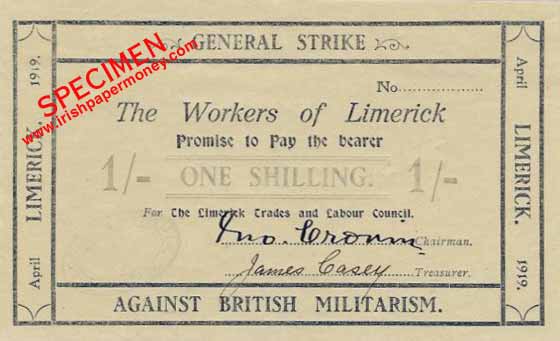

This victory only boosted the confidence of the masses. Elected workers councils in the form of soviets were established across the island, most notably in Limerick, where a general strike saw a soviet take control of the city for 2 weeks in April 1919. It controlled entry and exit from the city, distribution of food and even printed its own currency. The question was posed: who should rule-British imperialism and their lackeys in Ireland, or the masses?

The Irish ruling class conveniently forget these events when speaking of the War of Independence. Contrary to their fairytale explanations, Sinn Fein and the IRA had nothing to do with these movements. On the contrary, these petit-bourgeois and bourgeois nationalists showed themselves to be the enemies of labour at every turn, calling on the strikes to end. The slogan they put forward was ‘Labour must wait’; independence was proclaimed as the priority and ending the economic and social suffering of the working class was pushed to one side. This position was taken with the complete acquiescence of the leaders of the labour movement, who after the death of James Connolly, abandoned a class position and capitulated to right-wing nationalism.

Fear of revolution

The struggle of the working class during this period was the real resistance that took place, not the wasteful guerrilla struggle that Sinn Fein carried out as is depicted in the series. It was the fear of revolution that the working class inspired that brought the British to the negotiating table and caused them to divide the island in late 1921. The north, remaining under British control, fell under the control of Orange reaction and effectively became an apartheid state, while the south became a ‘Free State’, i.e. a dominion.

Such a division would keep Ireland dependent on British imperialism and encourage sectarianism, splitting Irish workers on religious lines to ensure that the power of labour could never rear its head again. The partition of Ireland was a defeat for the working class, a betrayal accepted and carried out by the majority of the leadership of Sinn Fein and the IRA.

This fundamentally demonstrated that they were incapable of achieving the national liberation of Ireland. As Connolly once said, the Irish ruling class had a thousand threads connecting them to British imperialism, just as many as any threads connecting them to nationalist sentiment.

Legitimisation

Since the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which implemented the partition system, Irish capitalism has sought to legitimise this state of affairs and paint the civil war that followed it as nothing but a tragedy. RTE’s Resistance follows this line once again to the mark, covering the events of partition in its last 30 minutes, portraying it as a necessary compromise.

Collins, one of the main architects and advocates for the Treaty is portrayed sympathetically, while the anti-Treaty Eamon de Valera, the leading political figure within Sinn Fein, is portrayed in both series as a ruthless and authoritarian leader. Although de Valera was no friend of the working class and likely opposed the Treaty on purely opportunist grounds, the intent of the series is clear.

Suddenly, several characters who the viewer has grown attached to over the past six episodes, are painted in a negative light for opposing partition, bringing violence and war to an island that had just gained peace. This is nothing new.

Colonial brutality

The series did have some positives however. In particular, it highlighted the bloody and brutal actions of the British state in Ireland. To crush the revolution developing in its nearest colony, British imperialism mobilised the full force of the capitalist state.

The series did have some positives however. In particular, it highlighted the bloody and brutal actions of the British state in Ireland. To crush the revolution developing in its nearest colony, British imperialism mobilised the full force of the capitalist state.

Armed bodies, such as the Royal Irish Constabulary and most infamously their auxiliaries in the form of the Black and Tans – containing the most reactionary elements in society and under direction from the British administration in Dublin Castle – engaged in torture, rape and murder. The series depicts these atrocities in all their horror. In particular, the beginning of Episode 2 sees a RIC raid on an IRA hideout, a scene which does not shy away from the brutality, especially against women, perpetrated by the agents of British imperialism.

What is also notable is the somewhat unprecedented negative role that the Catholic Church has within the narrative. A key part of the storyline is that Ursula Sweeney, a secretary at Dublin Castle, sees her baby taken away by a nunnery and then forcefully adopted by an American couple. In desperation, she goes to the IRA for help. This was actually based on a true story, that of Josephine Marchment Brown. It reflects the dominant and reactionary role that the Church has played in Ireland. For decades, the Church has held a huge influence over the Irish masses and acted as a major point of support for the Irish ruling class. This itself reflected in its portrayal in the official line as a benevolent guardian of moral values. Resistance has completely changed this, which is indicative of the decline of the Church’s power over the past few years.

Overall however, the narrative that Resistance puts forward is farcical and is somewhat of a step back compared to the previous series, Rebellion, created to mark the 100th anniversary of the Easter Rising in 2016.

The Easter Rising

Much like the War of Independence, the ruling class has developed myths around this too, iconising the Rising as a purely nationalist blood sacrifice; led by naïve idealists who had no support from the Irish masses. Rebellion broke this narrative in a way not seen before.

Most notably, it gives a great deal of prominence to the ICA and its revolutionary socialist character, with two of the protagonists, worker Jimmy Mahon and student Elizabeth, fighting in its ranks. It is shown to be an army of workers and trade unionists and although he is portrayed in a simplistic manner, Connolly is, for once, not just another nationalist, as the Irish ruling class have traditionally iconised him as.

Army splits

The series also portrayed dissent and splits within the British army repressing the Rising, with several characters expressing great hesitation and resistance to carrying out executions of rebels and civilians. Revolutions are decisively won when splits in the armed forces take place on class lines.

As seen in Russia in February 1917, it is the lower-ranking, conscripted men and women of working class origin who side with the masses, while those part and parcel of the capitalist state, the high ranking commanders, tend to side with reaction, although this is not always the case.

Above all, this highlights the critical mistake that Connolly and the insurrectionaries made in not making an internationalist appeal to British soldiers, spreading propaganda to win support.

For a Socialist Republic

Despite the positives, some areas remain glued to the fundamentals of the myth; that this was a noble attempt at Irish freedom, but such a Rising should not be attempted again. It remains depicted as an insurrection despised by the Irish people, with crowds booing the surrendered rebels. The Rising is portrayed as nothing but a mistake and for the worst. The message it broadcasted was clear: revolution is a dangerous and tragic business. Stay away from it!

This is unlikely to resonate with the Irish working class, who, under the crisis of capitalism, have begun to show their power. Last year saw a devastating blow made against the Catholic Church, with almost one and a half million people turning out to vote to abolish the 8th Amendment, which denied women the right to abortion. January and February saw an unprecedented strike by nurses against the horrendous conditions that they face and which, if not for the betrayal by the leadership of the trade unions, could have resulted in the beginning of the end for the Fine Gael-Fianna Fail government. The local elections in May saw the duopoly’s combined vote reduced to less than 50%, whereas only several years ago their vote share was in the 70s. This was a huge blow to the old order, as these two parties have ruled the country since the 1930s.

The Irish working class should ignore the fantastical nationalist myth that Resistance advocates and instead look at the revolution to demonstrate what they are. The failure of the Irish Revolution was ultimately due to the lack of an organised Marxist tendency in the labour movement, one that would not capitulate to bourgeois and petit-bourgeois nationalism, but would win the masses over to a radical socialist programme and unite the struggles of the working class. The need for this tendency and for the establishment of a Socialist Republic is now more pressing than ever.