Exactly 10 years ago I started my university career. I remember how nervous I was to enter the university for the first time. University was something big and scary to me, an institution full of knowledge and wisdom.

Now, 10 years down the line after my first step into the introductory lectures of a psychology degree, I find myself on the other side of the fence. Now I am a postdoc or a so-called Researcher B involved in research and teaching duties.

I was very nervous and excited before teaching my first class. It was basic statistics for first year psychology students. As well as teaching, I had some marking to do. The course coordinator explained to me that I get paid the normal teaching hour as well as for every feedback on the corrected and marked lab report and that it was estimated that it would take a maximum of 20 minutes to correct, to give feedback and a mark for each report according to the percentage-mark guidelines.

But basically the only thing, which was demanded of me, was to fill in the feedback sheet for each student. The feedback sheet consisted of a series of bullet points (such as title, introduction, result section etc.). These points were followed by a 1-4 rating scale, ranging from very good, to good, to satisfactory, to not so good. That was it.

In other words a student is asked to learn from the feedback given by his teacher, when the only feedback is whether your title was ‘good’ or your introduction was ‘satisfactory’. Any kind of educational psychologist will tell you that this is by far not the best way to improve learning in students. Since I did not agree with the way of feedback I decided to ignore the feedback sheets and gave every student an individual written feedback plus the mark I thought was appropriate.

Feedback

Logically it took me much longer than initially anticipated to mark a lab report, but I thought the students would benefit and hence it would be worth it. Based on the feedback and according to the percentage-mark guidelines I awarded marks to the individual reports. In the normal world one would always expect that marks similar to IQs, reaction times and so on to be distributed in a specific way, namely a few very good or high ones, a few very bad or low one, but the vast majority varying in the middle (in statistical terms this is called a normal distribution).

But the course coordinator did not want to wait until nature took its course and changed the percentage-mark allocation to such an extent until he had a few very good, a few very bad students and that the majority was in the middle. And then I was told that I had to use the new percentage-mark guideline from then onwards.

I rebelled and continued to give useful and accurate marks. The module leader decided to change the mark allocation guidelines again. I continued to mark the reports ‘properly,’ in the same manner as I did for the first one. Every time I did, the module leader created a new mark allocations sheet, which showed an artificially created normal distribution of marks for each lab report. At the end of the year he showed this to the department as evidence for successful teaching.

I was completely flabbergasted by all this and talked to other teachers and lectures and I was told that this was pretty common practice. And that no one really takes more than 20 minutes to give feedback on a lab report or essay, since the marking is more or less arbitrary anyway.

I was thinking very hard who could benefit from such a ludicrous way of marking? Certainly not me, because I spent a lot of time marking these reports but the actual marks did not reflect my opinion.

Feedback

Certainly not the students, because the feedbacks did not correspond with the marks. But how could they? I said that someone improved and should continue to take advice from the feedback when the actual percentages increased from lab report to lab report but the actual marks decreased as the result of making the reports fit the normal distribution. Certainly not the module leader, because he had to deal with the student’s dissatisfaction. Certainly not society, because it will be confronted with a lot of psychologist who haven’t been properly trained.

But what about the department and the university as such? Just recently I heard a speech of our vice-chancellor in which he said that he doesn’t call all the departments academic schools anymore but rather business units, that students are not students anymore, but customers. And then it dawned on me. Each student has to pay the university fee. Therefore, they expect a good service and, in terms of a university, this service should be an education.

Unfortunately, we have nowadays a slight misconception of a good education and think that a high mark in an exams or the degree is an index for a good education. But experiencing how marks are actually made up, only for the university to look good and therefore acquire more students for the next year, this seems to me not the best indication if someone learnt something or not.

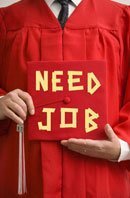

The sinister thing is that students are still made to believe that a good mark increases their employability which is, strictly speaking, not necessarily true. An average student with a 2.1 degree will find himself/herself at the end of the three years of studying with £20,000 debts but the average graduate job only pays less than £16,000 p.a. This would mean a long struggle until the first mortgage can be paid.

The sinister thing is that students are still made to believe that a good mark increases their employability which is, strictly speaking, not necessarily true. An average student with a 2.1 degree will find himself/herself at the end of the three years of studying with £20,000 debts but the average graduate job only pays less than £16,000 p.a. This would mean a long struggle until the first mortgage can be paid.

Altogether, universities are becoming more and more private enterprises, which are driven by the profit-motive and on the costs of the students, and therefore ultimately at the cost of society.

So much for the good old institution of knowledge and wisdom.