Rosa Luxemburg was born on 5 March 1871. Coincidentally, this was the same year that the workers of Paris rose up and established the Paris Commune: the first ever attempt by the working class to seize power. The euphoria that inaugurated the Commune was short-lived. After a couple of months the Parisian Revolution was smashed by the ruling class in a counter-revolutionary inferno of bullets and blood. In la semaine sanglante (“the bloody week”) that followed its crushing, 30,000 workers were murdered.

Almost 50 years later, in the year 1919, Rosa Luxemburg herself was murdered by the German counter-revolution as it crushed the uprising of the German workers. Her life coincided with the awakening of the working class in Europe, and was inseparable from the class struggle. She was no mere spectator to the world historical events with which her lifetime coincided: the First World War, the Russian Revolution of 1917, and the German Revolution of 1918.

Rather, she was an active participant in an attempt to change the course of human history. In her own words, Rosa Luxemburg saw that humanity was faced with the choice between barbarism or socialism. She threw herself into the struggle to ensure that it was the latter that triumphed. She fought to the last for world socialist revolution.

Iconic figure

Nowadays, Rosa Luxemburg is one of the most iconic figures on the left. The crisis of capitalism since 2008 has radicalised layers of society, particularly the youth, among whom there has been a revival of interest in revolutionary ideas and personalities. Rosa Luxemburg steps forth as a symbol of a woman who not only dared to stand up to the entire political establishment, but who in the end made the ultimate sacrifice in the struggle for socialism.

This growing interest in Rosa Luxemburg and her ideas are a sign that something is happening beneath the surface of society. More and more people are seeking to draw the lessons of history. This is extremely positive.

But Luxemburg is not simply an icon. Following her death, few other figures on the left have been surrounded by as much controversy. By every means of manipulation and distortion, a picture has been formed over time that is the antithesis of the revolutionary class fighter that she actually was. She is, first of all, represented as the woman, the feminist, the advocate of a ‘softer’, spontaneous socialism, in opposition to the October Revolution and Lenin.

Many of those who worship Rosa Luxemburg as an icon today are not aware of her history. As such, they are not aware of what she actually represented. If one attempts to find out more information about Luxemburg’s life and ideas, one is often confronted with this twisted and distorted image of her.

It is a lamentable paradox that the authority of Rosa Luxemburg is used today to justify reformism, softness and anti-revolutionary ideas. If one reads Rosa Luxemburg’s writings, there is no doubt that she was a revolutionary from the beginning to the bitter end. Everything she did and wrote was permeated by the fight for socialist revolution, a fight that cost her her life.

Reform or revolution

It is characteristic of her life that before she reached the age of 20 she was forced to flee from Poland to Switzerland to avoid arrest on account of her revolutionary activities. When she later moved to Germany to become active in the enormous German Social Democratic Party (SPD), she boldly threw herself into the pivotal debate that was raging at the time. In answer to the attempts of the reformist Eduard Bernstein to revise the ideas of Marx, Rosa Luxemburg presented the party with a brilliant defence of revolutionary Marxism.

The arguments of today’s reformists bear a striking resemblance to Bernstein’s. As such, Rosa Luxemburg’s critique retains its relevance to the debates taking place in the left. One hundred years on, Luxemburg’s reply to Bernstein, Reform or Revolution, is as relevant today as it was when it was written.

Rosa Luxemburg had warned that if the social-democratic movement abandoned the goal of socialist revolution, it would forfeit the right to exist. From a revolutionary lever for the overthrow of capitalism, it would become converted into a mere supporting pillar of capitalism. The history of social democracy has vindicated Rosa Luxemburg’s position.

But Reform or Revolution ought to be seen as more than simply a prediction of the fate that would befall social democratic parties. It should also stand as a warning to that “new” left which seeks to convert Rosa Luxemburg into an icon. Luxemburg would have had little time for this new left, which has discarded theory and which in reality has discarded any belief in socialist revolution along with it:

“What appears to characterise [reformism in practice]? A certain hostility to “theory.” This is quite natural, for our “theory,” that is, the principles of scientific socialism, impose clearly marked limitations to practical activity – insofar as it concerns the aims of this activity, the means used in attaining these aims and the method employed in this activity. It is quite natural for people who run after immediate “practical” results to want to free themselves from such limitations and to render their practice independent of our “theory.””

Rosa Luxemburg fought against the dissemination of reformism into the workers’ movement until the very end of her life. In every struggle she was to be found on the same side of the barricades: with the revolution.

Distortions

Attempts to distort the real picture of Rosa Luxemburg originate from various quarters. The ruling class, who are naturally enough concerned about preserving the status quo, and their power and privileges, attempts to paint a picture of Luxemburg as ‘bloody’ Rosa. They are interested only in scaring workers from rebelling by connecting the idea of revolution with blood and violence.

In reality throughout history it has been the ruling class which has spilt torrents of blood in defence of their system. It was the ruling class that brutally suppressed the German Revolution and murdered Rosa Luxemburg, along with so many other revolutionaries.

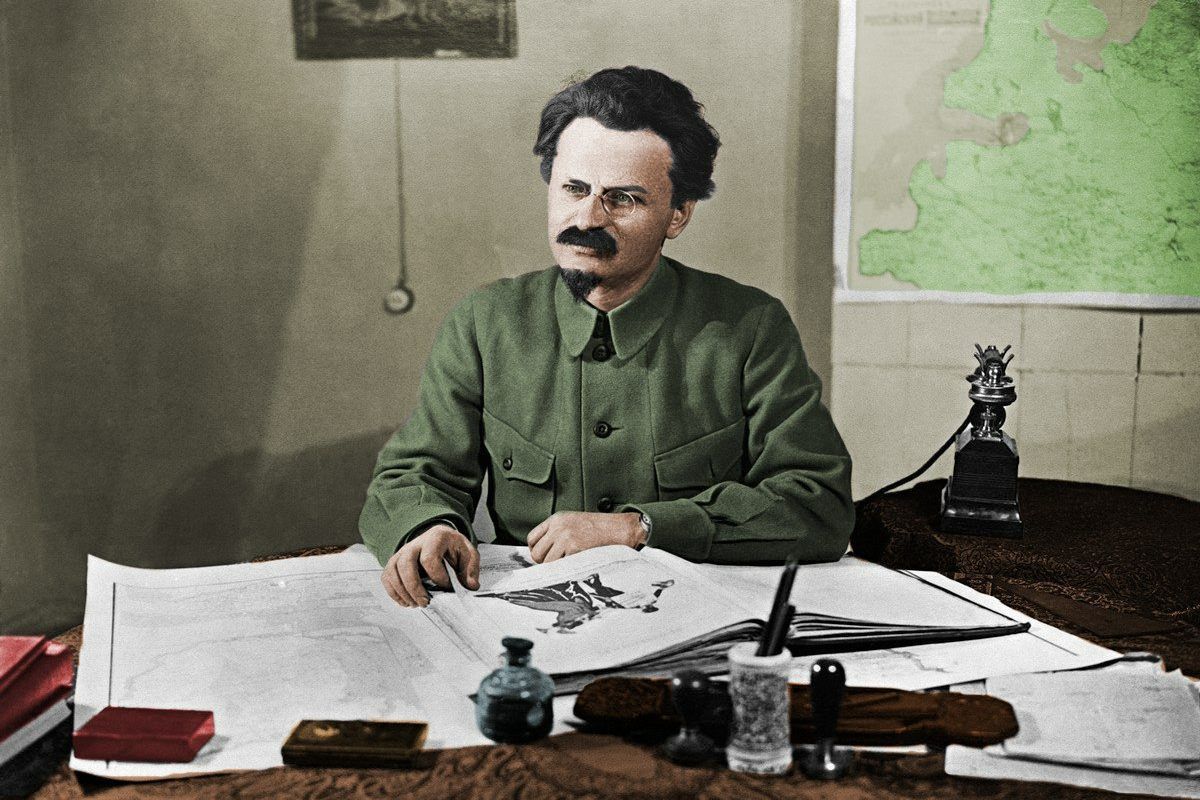

However, we also find a distorted image of Rosa Luxemburg originating from the left. In the first years following the October Revolution, when Lenin and Trotsky were still leading the young workers’ state, Rosa Luxemburg’s legacy was highly prized. She was recognised and celebrated as the revolutionary that she was. In 1922, Lenin even criticised the German Communist Party for having thus far failed to publish her collected works.

Luxemburg’s legacy in the communist movement, however, was inseparably linked to the fate of the Russian Revolution. The October Revolution had occurred in a backward country. Lenin and Trotsky’s perspective had always been to spread the revolution to the developed capitalist nations, and above all to Germany, as the only guarantee for the survival of the revolution in Russia and its development towards socialism. This was a perspective that Rosa Luxemburg fully shared and she did her utmost to fulfil it.

Unfortunately, the German Revolution was defeated, and the young Soviet state remained isolated. This was the foundation for the degeneration of the revolution and the seizure of power by a usurping bureaucracy led by Stalin. To consolidate his power, Stalin had to exterminate the Leninist, proletarian wing, not only of the Russian Communist Party but of the entire international communist movement. Stalin stopped at nothing. The left was physically exterminated and democracy was abolished. The revolutionary tradition was suppressed.

Like Trotsky and others who uncompromisingly struggled for a revolutionary policy, the ideas of Rosa Luxemburg soon found themselves in the crosshairs of Stalin and his henchmen. Stalin had to exterminate every revolutionary tradition and authority from the International. The Stalinist bureaucracy was terrified that the ideas of Luxemburg might inspire young communists to question their policy. Her memory, therefore, had to be smeared.

In 1923, the leader of the German Communist Party, Ruth Fischer, described Luxemburg’s influence on the German labour movement as “syphilitic”. And in 1931, Stalin himself entered into the smear campaign with an article titled, “Some Questions Concerning the History of Bolshevism”, in which he placed Luxemburg in the reformist, anti-Leninist camp. As he so often did, Stalin achieved this little maneuver by the shameless twisting of historical facts.

The Stalinists pointed to Luxemburg’s polemics against Lenin and used them to fabricate the myth of ‘Luxemburgism’: a distinct, reformist, anti-Leninist theory, in which the spontaneous movement of the masses was elevated to an all important position, in opposition to organisation and the party.

She was blamed by the Stalinists for all of the defeats and mistakes of the German Revolution in the years after her death, deflecting attention from the fact that responsibility for these mistakes lay with the advice and instructions the German Communist Party received from the leading layer of the Communist International, which was increasingly composed of individuals from Stalin’s inner circle.

It was up to Leon Trotsky, who together with Lenin had led the Russian Revolution in 1917 and who following Lenin’s death in 1924 had fought against the Stalinist bureaucracy, to defend Rosa Luxemburg against Stalinist smears:

“Yes, Stalin has sufficient cause to hate Rosa Luxemburg. But all the more imperious therefore becomes our duty to shield Rosa’s memory from Stalin’s calumny that has been caught by the hired functionaries of both hemispheres, and to pass on this truly beautiful, heroic, and tragic image to the young generations of the proletariat in all its grandeur and inspirational force.”

‘Spontaneity’

As Stalin consolidated his position, the anti-Stalinist left developed a renewed interest in Luxemburg, on account of the bile that the Stalinists directed towards her. But in the struggle against Stalin, there was a tendency to go too far in the opposite extreme. That is to say, this anti-Stalinist left effectively accepted the invention of ‘Luxemburgism’ and argued not only for the rejection of Stalin’s legacy, but that of Lenin as well.

They mistook Stalin’s distorted image of Luxemburg for the original and began defending it. This mythical Rosa Luxemburg, who supposedly advocated ‘spontaneity’ in opposition to organisation – an anti-revolutionary position – was defended by this left as essentially something positive. Trotsky criticised this ultraleft tendency to “make use only of the weak sides and the inadequacies which were by no means decisive in Rosa; they generalize and exaggerate the weaknesses to the utmost and build up a thoroughly absurd system on that basis.”

This is how things stood when Rosa Luxemburg’s ideas were once more brought to the fore during the revolutionary wave that swept the world in the late 1960’s. Rosa Luxemburg was held aloft as an icon for the new, anti-authoritarian, anti-Stalinist left, the so-called “New Left”.

But in actual fact they were merely repeating the same Stalinist lie: that of the “soft” Luxemburg, who simply focused on the spontaneity of the masses, as the antithesis of Lenin. In this tradition, for instance, one finds Bertram D. Wolfe who, in the early 1960’s published a collection of Rosa Luxemburg’s writings titled “Leninism or Marxism?”

Wolfe was a former communist who had left the communist movement and had instead made an academic career for himself. In his book one finds Luxemburg’s article, “Organisational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy”, under a new title that Wolfe had chosen for it: “Leninism or Marxism?” In this article from 1904, Luxemburg expresses criticisms of Lenin’s view of the revolutionary organisation. It is thus used to paint Rosa Luxemburg as the “democratic”, “anti-authoritarian”, and “humane” socialist as opposed to Lenin’s centralist and “authoritarian” disposition.

What Wolfe fails to mention is that after the first Russian revolution of 1905, Rosa Luxemburg explicitly stated that the critique she had aimed towards Lenin was a thing of the past. Here, in her own words, is Rosa Luxemburg’s opinion of Lenin and the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution of 1917:

“The Bolsheviks have shown that they are capable of everything that a genuine revolutionary party can contribute within the limits of historical possibilities. […] In this, Lenin and Trotsky and their friends were the first, those who went ahead as an example to the proletariat of the world […] This is the essential and enduring in Bolshevik policy. In this sense theirs is the immortal historical service of having marched at the head of the international proletariat […].”

Personal vs political

There remains a large quantity of Luxemburg’s writings that are yet to be translated, not only from Polish to English, but also from German to English. Among the portion of Rosa Luxemburg’s writings that have been translated and published are her letters. Shortly after Luxemburg’s death, her letters from prison to Karl Liebknecht’s wife Sophie were published. A couple of years later Louise Kautsky, the wife of Karl Kautsky and a close friend of Luxemburg, published her correspondence with Luxemburg.

The intention of publishing this entire correspondence was to disprove the ruling class’ public portrayal of Rosa Luxemburg as “bloody Rosa”: a cold, cynical fanatic of violence; an image that was promoted to justify her murder.

By bringing these letters into the light of day, the intention had been to show that she also had an emotional and empathetic side. The letters did indeed change public opinion. However, the picture they presented was also quite one-sided. It was an image from which the revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg vanished.

A number of Rosa Luxemburg’s letters to Leo Jogisches, with whom she essentially lived as a partner for 15 years, were translated from Polish and published by Elzebieta Ettinger under the title, Comrade and Lover in 1979. Ettinger details in the preface how she, naturally enough, had to select which of the roughly 1,000 letters in the Luxemburg-Jogisches correspondence she wished to translate. According to her, there were three possibilities: correspondence relating to Luxemburg’s involvement in the Second International; her involvement in the German and Polish Social Democratic Parties; or her personal relationship with Jogisches:

“While the first two would have provided students of the European, and especially the Polish, Russian, and German movements, with a wealth of material, they would have left Luxemburg as she is at present – faceless. The third choice would reveal a woman, hitherto unknown, whose sex did not diminish her political stature and whose politics did not interfere with her private life. It would also expose the fragility of the concept that a woman cannot, without giving up love, realize her talent.”

A translator naturally has the right to translate anything they wish. But Ettinger is not the only one to highlight Rosa Luxemburg ‘the woman’, rather than Rosa Luxemburg the revolutionary. Rosa Luxemburg was also a private person. Did she really wish to have her highly personal letters to her lover published?

This focus on the personal completely overshadows the fact that Luxemburg was first and foremost a revolutionary. Yes, she was a woman, she was Jewish, she was a Pole. But above all she saw herself as a part of the international struggle of the working class for socialism; a struggle that cuts across all of these divisions.

In a letter to Mathilde Wurm written on the 28th December 1916, when Luxemburg was still imprisoned, she writes on the subject of being human:

“As far as I am concerned I was never soft but in recent months I have become as hard as polished steel and I will not make the slightest concessions in future either politically or in my personal friendships. […] To be human is the main thing, and that means to be strong and clear and of good cheer in spite and because of everything, for tears are the preoccupation of weakness. To be human means throwing one’s life ‘on the scales of destiny’ if need be, to be joyful for every fine day and every beautiful cloud – oh, I can’t write you any recipes how to be human, I only know how to be human […]. The world is so beautiful in spite of the misery and would be even more beautiful if there were no half-wits and cowards in it.”

The story of Rosa Luxemburg has to be written as if we were writing about any of the other great revolutionaries: as the story of ideas and works, without becoming absorbed in stories of feelings and into an individual’s love life.

Emancipation

In the recent years it has become fashionable to call Rosa Luxemburg a socialist feminist. The increasing focus on the women’s question today is a sign that we are entering a revolutionary period. More and more people are beginning to question the status quo and rise up in opposition to inequality and oppression. This is an extremely positive development.

Rosa Luxemburg fully supported equality between women and men, and the emancipation of women as part of the emancipation of mankind. But she never called herself a feminist. To call her a feminist now is to impose conceptions drawn from the present onto the past in a way that distorts the actual opinion of Rosa Luxemburg.

First of all, Luxemburg wrote very little about the women’s question. This was not because she thought it unimportant, but because she was busy with other things. Upon her arrival in Germany, the leadership of the SPD attempted to file away this young and rebellious woman, whose presence was so inconvenient to themselves, by proposing that she become active in the women’s movement of the SPD.

Luxemburg refused outright. Instead she threw herself into all the great theoretical debates raging in the SPD. She was also fiercely opposed to the bourgeois and the petty-bourgeois women’s movement. For her, the only way to secure the emancipation of women was through the struggle of the working class for a socialist revolution. In this struggle, bourgeois women would not be on the side of working-class women.

Rosa Luxemburg is clearly an inspiration to many, both women and men, all over the world. This is because she played a prominent role in the international working-class movement – despite the barriers she faced on account of her sex. But that should not cause us to demean her ideas and works as inspirational simply because she was a woman.

She is an inspiration because she was consistently revolutionary to the bitter end. Lenin described her as one of the “outstanding representatives of the revolutionary proletariat and of unfalsified Marxism”. It is for this that she ought to be remembered: for her revolutionary legacy.

If one wishes to change the world, one has to understand it. This requires us to learn from those who came before us. Luxemburg’s revolutionary legacy is paramount for all of us who wish to change the world.

But before we can learn from the experiences of Rosa Luxemburg, we must uncover her true legacy, removing the mountain of distortions, misrepresentations and smears that have been piled upon it.