“Lies, damned lies, and statistics” is a well-known aphorism for a reason. By massaging the figures cleverly, it’s possible to ‘prove’ anything.

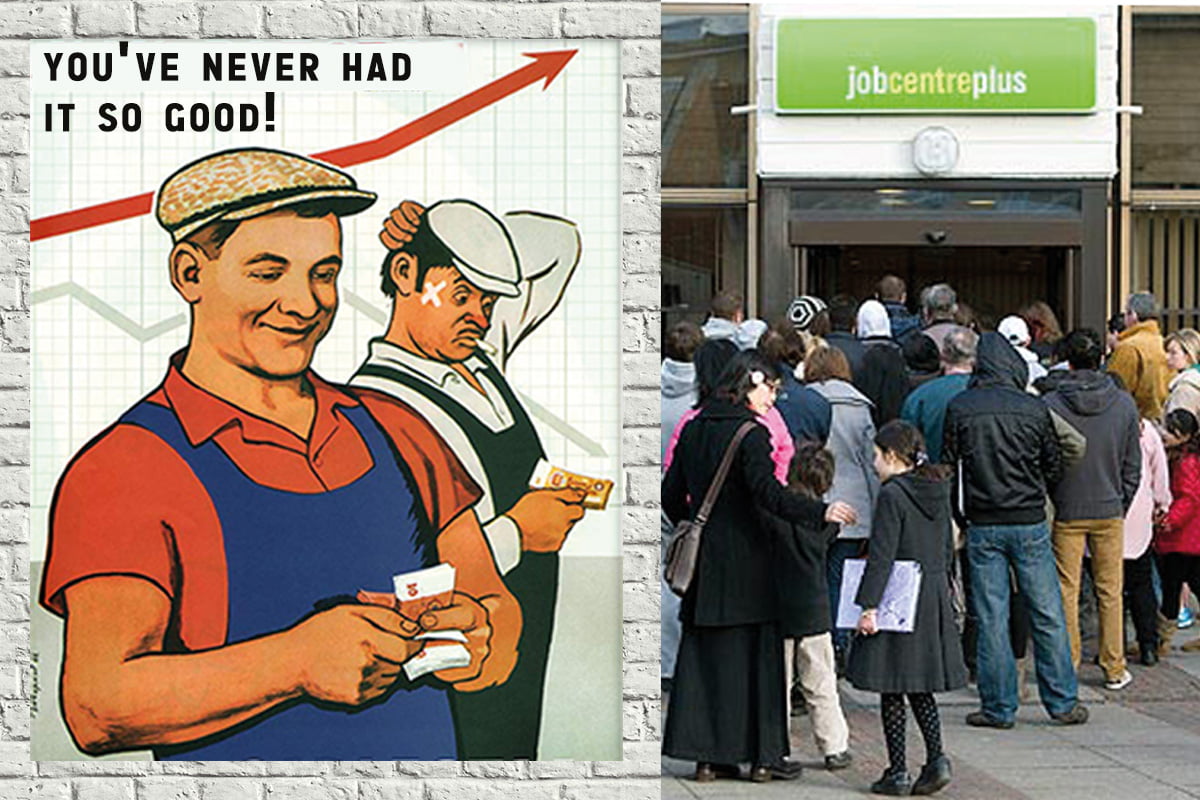

Last year, The Economist magazine ran a series of articles claiming that workers have ‘never had it so good’. Real wages are better now than they have been in decades, we’re told. The income differential between the very top and the very bottom is apparently shrinking.

Strangely enough, though, workers everywhere are clearly still angry. Our learned, liberal journalists have the answer to this riddle, thankfully. It’s all a question of ‘narrative’. These workers, despite everything, simply believe that they are worse off.

So that’s all right then! There’s just one small question: are these optimistic assertions true?

Are real wages growing?

Firstly, let’s look at the question of real wages – pay adjusted for prices. The Economist’s data ranges from 2019 to 2023, a conveniently short span of time.

Pointing to a 3% and 1.5% real-terms pay increase in the USA and Britain, respectively, we are invited to breathe a sigh of relief.

Unfortunately, the facts – as they say – don’t select themselves. And a wider time range produces a rather different picture.

As the journal’s authors themselves admit, if real wages are examined from their pre-crash peak in 2008, instead of from 2019, we find that workers’ purchasing power in the UK has in fact dropped by 4.7% over this period. This tallies with the results of analysis by the TUC.

Real wages, in reality, are very difficult to measure. It may well be true that, when overall wages are compared to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), they appear to have grown.

The first problem, however, is that CPI is a notoriously inaccurate measure of inflation. It doesn’t even track things like housing costs. Skyrocketing rises in rents and energy across Britain have clearly eaten into what wages can actually buy. But CPI doesn’t fully reflect this.

If we then factor in the scourge of unpaid overtime and overwork (which in practice means that workers are being paid less for the work they actually do), or the slashing of public services (which represent a part of the ‘social wage’ that workers receive and rely on), then The Economist’s arguments look even shakier.

Wage inequality

Let’s now examine the magazine’s claims about wage differentials. The very lowest are seeing their wages rise at a notably faster rate than the very highest, according to the data The Economist provides.

They say that this indicates that income disparity in general is narrowing, in direct contrast to ‘conventional wisdom’, thereby disproving the idea that the capitalists are hoovering up the lion’s share of the newly-generated wealth in society.

The problem is that this is simply nonsense. Measuring wage differentials tells us nothing about the gap between workers and capitalists – because the latter, by definition, aren’t paid wages. Instead, the bosses, landlords, and bankers appropriate surplus value created by the working class, in the form of profits, rents, and interest.

This data therefore tells us precisely nothing about the gap between those who work in production and those who own the means of production. Nor does income disparity tell us much about the inequality in wealth between the super-rich and the rest, which is another matter.

All this data shows is that the gap between the best-paid and least-paid wage-earners is narrowing. But even this is more a reflection of levelling down, through the deskilling and ‘proletarianisation’ that runs rampant throughout the economy, than of any real gains made at the lower end.

Taxing the rich

If we do examine wealth inequality, the contrast between the billionaires and the billions – in contrast to what the apologists of capitalism might assure us – has never looked starker.

Indeed, Oxfam has recently shown how the wealth of the world’s five richest individuals has more than doubled since 2020. Meanwhile, the planet’s poorest 60% have gotten poorer in that same time.

The solution demanded by Oxfam – and other reformists – is for a number of taxes on wealth and profits, alongside stronger intervention by governments to bust monopolies.

But as long as production is privately owned by the capitalist class, widening inequality is inevitable. Wealth concentration isn’t a mistake of “runaway corporate power”, but an unavoidable feature of the capitalist system itself.

Instead of scrabbling for larger scraps from the master’s table, we must fight to socialise the means of production, and place them in the hands of the working class, in order to plan production for need.

Supply and demand

The Economist makes two further arguments worth examining.

The first is that relative tightness in the labour market – due to a mixture of deficit spending and ageing populations – is driving wage growth. In other words, we are told that it is simply a case of supply and demand (of labour-power) pushing up wages.

Supply and demand do play a role in determining prices, including the price of labour-power. But the key factor determining what workers receive from the bosses is class struggle.

Indeed, the refrain of the capitalists during this time has been for wage restraint, not wage rises. And where pay claims have been made, the employers have generally resisted them ferociously. Clearly they aren’t prepared to allow supply and demand to dictate their labour costs!

Without organisation and struggle, Marx stated, the working class is only “so much raw material for exploitation”. In other words, all things being equal, the bosses will exploit workers as ruthlessly as they can, in their pursuit of profit.

To maintain their living standards in the face of the bosses’ attacks, workers have had no choice but to organise and strike back. It is no accident that the last couple of years have seen tremendous strike waves in both Britain and the US, with a reawakening of the working class.

A silver bullet

The Economist turns to generative AI for its second argument. They suggest that this transformative technology could “unlock” huge productivity gains in almost every sector. In turn, a larger economic pie will automatically guarantee the working class a greater slice.

This is complete speculation, however, as even The Economist itself admits. They have no idea to what degree AI can improve the productivity of labour in general, or which sectors of the economy it will actually be integrated into.

The capitalists treat AI as a silver bullet; as a panacea that they hope can save them and their system. Thus far, however, hype around this technology has largely failed to materialise in any concrete sense.

But let’s pretend for a minute (as The Economist does) that AI is in fact certain to lead to a leap in productivity.

Under capitalism, historically, the primary consequence of new productive technologies and techniques has been to throw one section of workers onto the scrapheap. Those who keep their jobs, meanwhile, are forced to work even harder. All the while, it is the capitalists who benefit, as labour costs decrease and profits rise.

Once again, it is class struggle – not technology – that forces the capitalists to give up a larger share of the surplus value that workers create. Without this, any increase in productivity inevitably comes hand-in-hand with greater exploitation, and greater returns for the capitalists.

Overthrow their system

In the end, The Economist’s efforts are a case of smoke and mirrors. All they really amount to is a comforting bedtime story for bankers and bosses everywhere – one that these ladies and gentlemen are sure to soon get a rude awakening from.

The truth is that workers are not angry because they have fallen for a false ‘narrative’. They’re angry because they can see that their lives are getting no better, while a handful of billionaires get richer by the hour.

The Economist – like the rest of the capitalist media – does not really understand the system it defends. And they have no interest in understanding it. As long as the profits keep flowing in, all’s well as far as they’re concerned.

Ironically, it’s the communists who best grasp the realities of the capitalist economy. We strive to understand capitalism, however, so that we can fight to overthrow it – and replace it with a system that would genuinely raise living standards for the vast majority, and improve life for all of humanity.