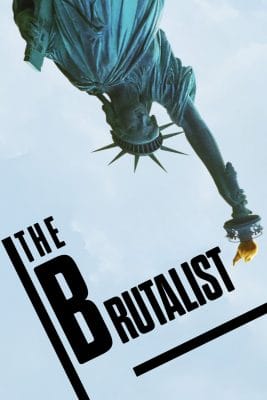

Brady Corbet’s new film The Brutalist is as monumental and ambitious as the concrete-heavy, post-war architecture from which it takes inspiration.

It is an impressive enough feat on its own that a film about the life of an architect can hold the audience’s attention for more than three hours.

In the first half, this is achieved by slowly revealing the backstories and motivations of the characters.

Adrien Brody is both subtle and intense in the role of László Tóth, a Jewish-Hungarian architect trying to create a new life in the US after surviving the horrors of the Holocaust.

His character was inspired by an amalgamation of several Bauhaus artists who made the same move from central Europe following the Second World War.

‘American Dream’

Depicting a difficult (but apparently ultimately triumphant) version of the ‘American Dream’, we watch as our protagonist finds a wealthy patron who pulls him out of poverty and obscurity, and arranges for his wife to join him in the US.

Yet the tone of The Brutalist is made clear from the outset, in a letter from László’s wife. Quoting Goethe, she observes that “none are more hopelessly enslaved than those who believe that they are free”.

And sure enough, after the interval, things begin to rapidly unravel for the couple – and for László’s architectural project

Through this process, the real cruelty which permeates bourgeois American society becomes clear.

Until this point, the disdain that the ruling class holds for those they consider beneath them – manual workers, foreigners, minorities – has been hidden behind a thin veil of jovial, boom-era confidence.

This illusion is swiftly removed in a single, hard-hitting scene of disturbing violence.

As we watch László’s work progress on a variety of public and private projects, there are more hints at deeper political questions that the film does not answer.

Brutalism, along with other modernist architectural movements, aimed to bring a functional elegance and a certain idea of beauty – not just to the bourgeoisie but to the masses.

Yet for the brutalist architects, their dream of changing society from the ivory tower of an architecture studio crashed time and again against the realities of life under capitalism.

However, the scope of The Brutalist drives it away from engaging with the failures of this architectural movement.

Nonetheless, it absolutely succeeds as a film. For example, the utilisation of camera angles to build tension, and the use of archive footage to set the backdrop of the historical scenes, are excellent.

The nature of art

The film also poses some powerful ideas about the nature of art itself.

Throughout the second half, new events and details give us an entirely new perspective on everything that we saw before. The film’s apparently simple structure is turned on its head, pushing the viewer into new interpretations.

In the same way, we find out that this project we have watched take up years of László’s life was not merely an aesthetic statement, but a way for him to continually reflect on his memories and reinterpret his trauma.

Both the film and the architecture within it point to the same idea: that art has its own laws and logic, while at the very same time reflecting the experiences and consciousness of the artist and of society as a whole.