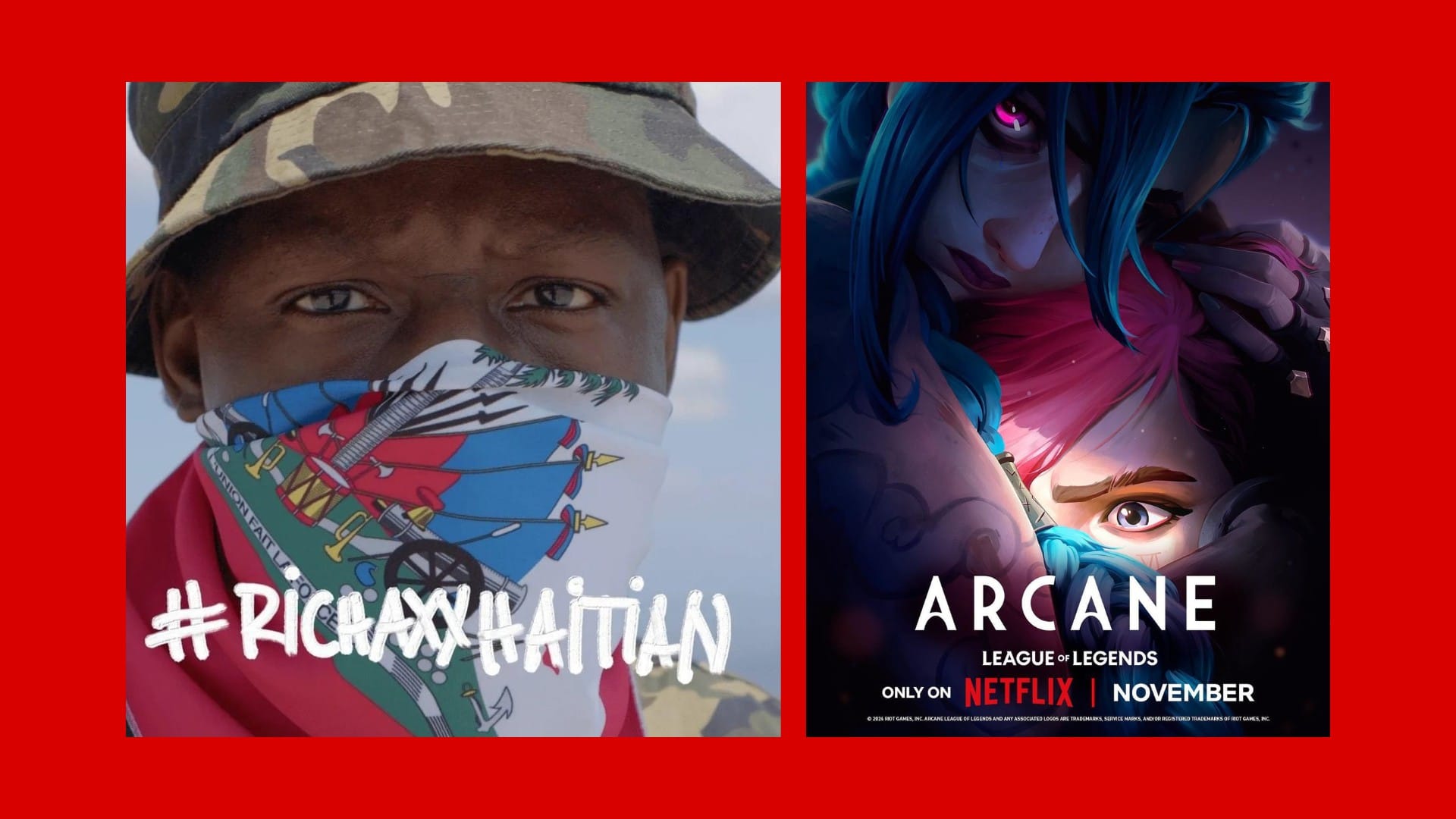

#RichAxxHaitian

Said Moredi, Milton Keynes

Mach-Hommy, the enigmatic figure on the fringes of the music industry, once again celebrates Haitian culture in his recent album, #RichAxxHaitian.

Released just before Haitian Flag Day – a public holiday celebrating the adoption of the Haitian flag during the Haitian Revolution – this album marks the fourth instalment in his ongoing series exploring Haiti’s history, culture, and struggles.

The journey began in 2016 with the release of HBO (Haitian Body Odor), which featured the striking cover art of Michèle Bennett Duvalier, former First Lady of Haiti, in her wedding dress.

That album delved into themes of poverty, unemployment, and the masses’ disgust at the wealth and decadence of Haiti’s ruling elite, juxtaposed against the abject poverty of ordinary people. It culminates in the overthrow of the Duvalier dictatorship, a symbol of resistance against oppression.

In 2021, Mach-Hommy challenged the passivity of performative solidarity with Pray for Haiti. This second instalment in his Haiti-themed works rejected the notion that the Haitian people need prayers.

Instead, it demanded revolution – an uprising to expel the imperialist-backed gangs and puppet government officials, putting power back where it belongs: in the hands of the masses.

Later that same year, he released Balens Cho (Hot Candles), opening with a skit of an American man cynically advising others to profit from Haiti’s export-import business.

The album expands on themes of exploitation, exposing the corrupt Haitian elite and their alignment with U.S. imperialist interests, which drain the nation of its riches.

In #RichAxxHaitian, Mach-Hommy continues this scathing critique. On the track ‘POLITickle’, he references the atrocities in Gaza with the line, “White phosphorus fell on civilians in Gaza,” and condemns the ruling classes as “Troglodytes squadron spitting epithets and jargon.”

He further indicts global capitalist institutions, rapping, “International Monetary Fund, I got a monkey on my back, and it’s a rather heavy one.” This is a stark acknowledgment of Haiti’s $180 million debt to the IMF and the organisation’s vampiric grip on the nation’s economy.

The song ‘SUR LE PONT D’AVIGNON (Reparation #1)’ begins with a French nursery rhyme, evoking Haiti’s history as a French colony – and the seismic impact of the French Revolution on Haiti’s own revolution.

The Haitian Revolution, the first successful colonial slave revolt in history, is a testament to the power of the masses to defeat colonial oppression.

Mach-Hommy connects this legacy to the present, declaring on the track ‘XEROX CLAT’ the need to “get rid of the cancer from the roots” – a clear reference to capitalism and its parasitic hold on Haiti.

He condemns the control a “handful of businessmen in a room somewhere” hold, with their “avaricious, hyper-capitalistic aims,” emphasising that true liberation requires removing these forces entirely.

Through his music, Mach-Hommy highlights that only a revolution led by workers and the poor can truly transform Haiti.

Like the first Haitian Revolution, a modern uprising would inspire the rest of the Caribbean to expel imperialist forces.

Just as the 18th-century revolt sent shockwaves through colonial powers in Barbados, Jamaica, and beyond, a socialist revolution in Haiti could serve as a beacon of hope for the oppressed throughout the region.

Mach-Hommy’s #RichAxxHaitian stands as a defiant critique of imperialism and capitalism, rooted in a profound love for Haiti and its people.

‘#RichAxxHaitian’ is available on Spotify and other streaming platforms.

Small Things Like These

William Gedling, Manchester

“Why were the things that were closest so often the hardest to see?” – Claire Keegan

Enda Walsh’s adaptation of Claire Keegan’s novel Small Things Like These quietly yet profoundly explores the horrors and exploitation of women by the Catholic Church in Ireland.

Our story starts when Bill (Cillian Murphy) discovers a young woman locked in a convent’s coal shed, exposing him to the horrors of the ‘Magdalene Laundries’.

Here, unmarried pregnant women – labelled “fallen women” – worked in exchange for “care” by the church. These mothers were then separated from their children, who were often sold to other families.

With an estimated 30,000 to 60,000 women confined to these laundries and the discovery of 155 unmarked graves, it’s staggering to consider that the last of these institutions only closed in 1996.

Haunted by his own past as the son of a single mother, Bill wrestles with whether to confront this injustice or heed his wife’s advice to ignore it: “Where does thinking get us? All thinking does is bring you down.”

Bill faces bribes and veiled threats from the Mother Superior, who warns him that his daughters may be denied entry to the local church-run school. The pub landlady also advises him to focus on his own family.

The film correctly points to poverty as central to the church’s power. We see this poverty throughout the film.

In one scene, Bill meets a child who’s walked far from town “collecting sticks” for a missing dog, though it’s clear the sticks are for firewood. Later, Bill sees a child drinking from a neighbour’s dog bowl.

The dialogue and score of Small Things Like These are minimal, leaving visuals such as these to communicate volumes.

Compared to his role as the eponymous Oppenheimer, Cillian Murphy’s portrayal of Bill feels like a whisper. Every character, in fact – even the threatening Mother Superior – feels restrained, reflecting the bleak, oppressive conditions that surround them.

Through witnessing Bill’s inner turmoil with no distractions, the sense of the church’s hold over people is allowed to resonate; it is a force so extensive that it seems to have “its fingers in all the pies,” as the landlady observes.

Although today the church as an institution is in decline, the scars of this period remain, and the power it still holds should not be underestimated.

The struggle Bill faces, that of fighting back against a system that reinforces poverty and oppression, carries on.

‘Small Things Like These’ is showing in cinemas now.

Arcane

Hugh and Sarah Nankervis, Oxford

The second and final series of Arcane has just concluded on Netflix, bringing to an end this award-winning animation.

For those uninitiated, the show is loosely based on the online multiplayer battle game League of Legends and set in Piltover, a hub of trade and scientific innovation – the ‘city of progress’.

We follow two sisters, Vi and Powder, who grow up in the polluted, downtrodden slums of Piltover – the ‘undercity’ – in the aftermath of a failed uprising against its oppression and exploitation at the hands of Piltover’s wealthy ‘topsiders’.

Through a series of tragedies of Shakesperian proportions, Vi and Powder end up on opposing sides in this struggle.

Powder – who takes the name of Jinx – becomes involved in the movement for the liberation of the undercity as the ‘nation of Zaun’, while Vi sides with Piltover’s police (the Enforcers) against the Zaunite’s terrorist methods.

This season saw an elevation of its already outstanding animation, alongside a continuation of an excellent soundtrack and fantastic voice acting.

Yet the ending left a bad taste in the mouths of those hoping for a resolution to one of the show’s key questions: reform or revolution?

In the first three episodes of this season, Arcane brilliantly continues its exploration of the struggle between the ruling class of Piltover and the oppressed masses of Zaun.

As tensions heighten, martial law and brutal crackdowns are perpetrated by Vi and the enforcers, while Jinx becomes a revolutionary icon in spite of herself as a result of her daring in fighting back against Piltover’s rule.

Largely, the Arcane writers avoid a heavy-handed approach – the show does not explicitly portray either side as “the right side”, nor does it give any definitive answers to the complicated questions it poses.

Instead, it allows for the characters to grapple with these, and for the audience to draw its own conclusions through this. This makes for excellent storytelling.

Sadly, midway through this second season, another plot thread overtakes and then thoroughly smothers the story of revolution. And from here, Arcane’s once-masterful storytelling falls like a house of cards.

Piltover has pioneered ‘Hextech’; technology that can harness magic. This has facilitated immense prosperity – for Piltover’s select few.

However, in season two we discover this has a hidden cost. Overuse of Hextech is leading to catastrophic environmental degradation – and has laid the groundwork for the development of a heavily-AI-coded supervillain looking to take over the world to boot!

Faced with the machinations of this supervillain, in short order the question of class struggle is set aside: the oppressed are expected to join with their oppressors to battle this existential threat.

The environmental damage done by Hextech; that this has happened at the hands of Piltover’s wealthy elite; that the impacts themselves are almost entirely restricted to the undercity – all quickly become a footnote.

How similar this is to the question of the climate crisis today.

We are told that we must put aside petty queries like ‘who is responsible for this ongoing destruction and why’ – and certainly ‘who is oppressing and exploiting who’ – to band together as humanity to save the planet.

And this is exactly what the Zaunites do – even wearing the uniforms of the Piltover enforcers who were brutalising them weeks earlier!

Perhaps it actually is clear which side Arcane falls on in the question it poses of reform or revolution. It is a shame it doesn’t give the same space for the audience to draw their own conclusions on this as it does for other questions.

For those who were expecting more from what is otherwise a beautiful and masterfully crafted piece of art, I commiserate with you. For those class fighters who’ve concluded they want to fight for a safe and sustainable society, I say: fight for revolution!

‘Arcane’ is available on Netflix.

Salt of the Earth

Rahul Mehta, Wood Green

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the release of Salt of the Earth, a dramatic retelling of the 15-month Empire Zinc strike of 1951.

The story of the strike itself carries important lessons for the labour movement, both in America and globally, today: how racism is used to divide and exploit workers, the class basis for the exploitation of women, the criminal role of the police and the titanic power of the organised working class.

The film follows the story from the perspective of Esperanza, wife of zinc miner Ramón and struggling under back-breaking domestic housework.

When the miners choose to strike over their pay (lower than their fellow “Anglo” white workers at other mines) and their conditions (regular industrial accidents), they’re met with the harsh reprisals of their boss.

Blocked from picketing by an injunction, the workers’ wives and sisters vote to build their own pickets to take on strikebreakers. While the women are also subject to police brutality, the striking men learn how difficult it is to run a home and raise children.

Just as interesting as the film is its production.

Written and produced by artists blacklisted by the McCarthyite kangaroo court at the time, the production crew had to hire local miners (who had actually taken part in the famous strike) as actors as unions banned their workers from working in blacklisted films.

The producers struggled to have the actual film spools developed, filming was marked by anti-Communist armed harassment and the film was suppressed for decades.

70 years on, the film remains evergreen.

As the capitalists seek to divide us based on skin colour, nationality, gender and more, Salt of the Earth and the strike that inspired it are potent reminders of the red thread of working class power that connects our struggle to that of the 1950s, and beyond.

‘Salt of the Earth’ is available to watch on YouTube for free.

Tsar to Lenin

Joshua HW, Cardiff

The documentary Tsar to Lenin (1937) provides a remarkable glimpse into the Russian Revolution, offering a unique opportunity to explore one of the most pivotal moments in modern history.

Constructed from the footage from over one hundred different cameramen, including footage intended originally as anti-Soviet propaganda, the documentary does not shy away from the epic reality of the Bolsheviks’ rise to power.

The American filmmaker Herman Axelbank began collecting the footage in 1920, and the compilation process took 13 years to finalise.

Axelbank enlisted Max Eastman, a prominent American writer, socialist, and an acquaintance of Leon Trotsky, to write the captions and provide narration.

Upon its release in 1937, the film was met with critical acclaim and high praise for its objectivity. The New York Post’s review of the film said it was done “extremely well”.

The documentary’s release coincided with the Moscow Trials, and Axelbank portrayed the chief defendant, Trotsky, in a favourable light, with recognition of his role organising the Red Army from scratch.

But, despite the initial favourable reviews, the film’s positive depiction of Trotsky resulted in a barrage of criticism by the Stalinist Communist Party of the USA, which organised a boycott against it.

A call to arms against the documentary appeared in the form of a big-headlined article featured in the Communist Party’s newspaper, The Daily Worker. This pressure resulted in several theatres not showing the documentary, and thus it was buried in obscurity.

I cannot recommend this documentary enough. It is a deeply insightful account of the revolution. After all the years it spent in the shadows, it deserves to be in the spotlight today.

‘Tsar to Lenin’ is available on Amazon Prime. (But if you don’t fancy handing money to Jeff Bezos, a version is available for free on YouTube).